West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

December, 2009

Presented Jon Wender, MD

A 45-year-old man presented with 3-day history of decreased vision in his left eye.

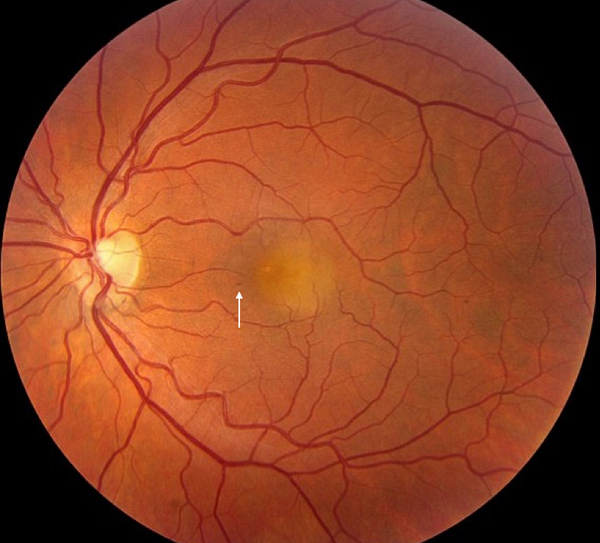

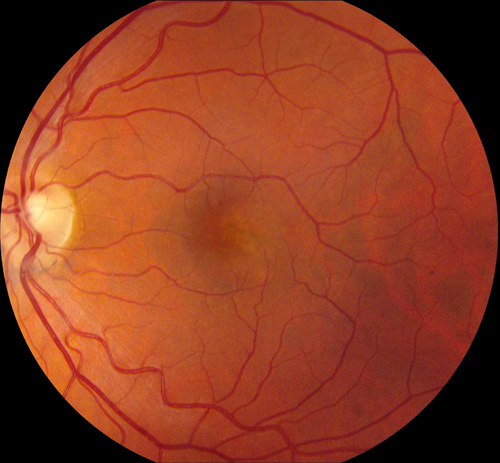

Figure 1: The fundus photograph of the left eye reveals a solitary, yellow subretinal lesion beneath the foveal center associated with a small intraretinal hemorrhage (arrow).

Case History:

A 45-year-old man presented with a three-day history of floaters and decreased vision in his left eye. Three weeks earlier, he had suffered a severe upper respiratory illness. His past ocular history was significant for bilateral LASIK, 8 years ago. His past medical, social and family history were noncontributory.

On examination, the visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/200 in the left eye. The intraocular pressure and anterior segment examination were normal in each eye. The right fundus was normal. In the left eye, a yellowish lesion with indistinct borders and subretinal fluid was noted (Figure 1). There was intraretinal hemorrhage located just nasal to the lesion. There was no evidence of anterior segment or vitreous inflammation.

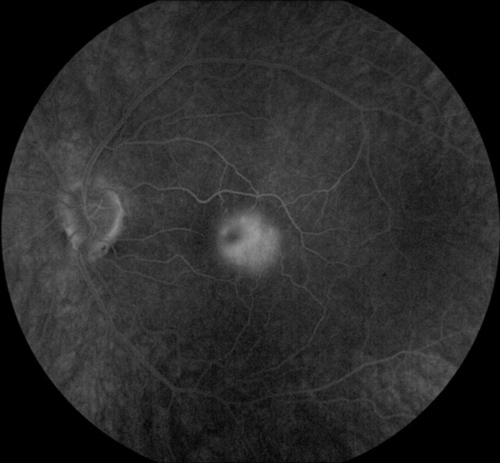

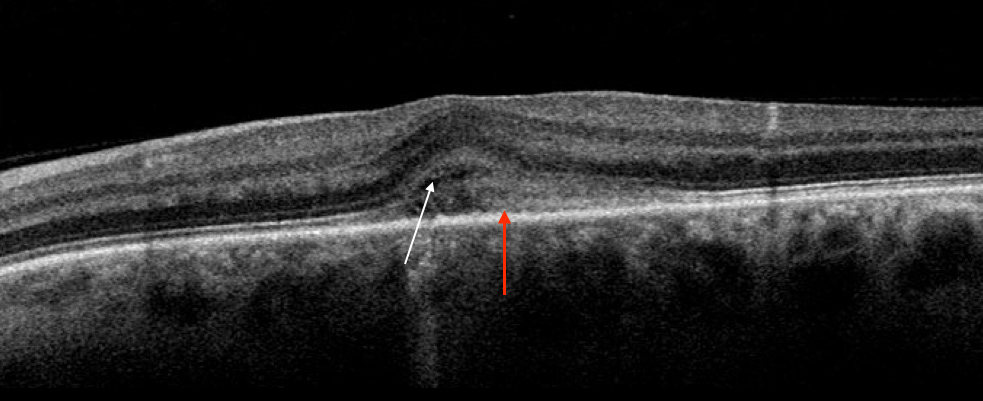

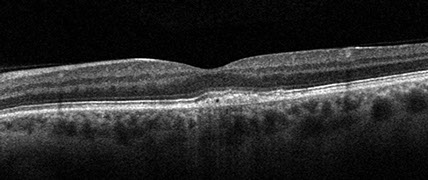

Fluorescein angiography of the left eye revealed hyperfluorescence of the submacular lesion (Figures 2). In the late phase, there was hypofluorescence centrally. Subretinal fluid as well as disruption of the photoreceptor inner segment / outer segment junction and thickening and irregularity of the pigment epithelium were evident with spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) (Figure 3).

A

B

Figures 2A and B: The fluorescein angiogram of the left eye reveals irregular early hyperfluorescence (Fig 2A) and nearly complete late hyperfluorescence associated with the subretinal lesion in the macula (Fig 2B) .

Figure 3: Spectral domain optical coherence tomography of the left macula reveals subretinal fluid (white arrow), thickening of the retinal pigment epithelium (red arrow) and disruption of the photoreceptor inner segment / outer segment junction.

What is your Diagnosis?

Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for this patient includes: central serous chorioretinopathy, idiopathic choroidal neovascularization (CNV), adult vitelliform macular dystrophy, focal choroiditis and a masquerade syndrome. Infectious causes of focal choroiditis include syphilis, tuberculosis, and nocardiosis. Non-infectious causes include sarcoidosis, acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE), and acute idiopathic maculopathy (AIM).

Fluorescein angiography was atypical for central serous chorioreinopathy. The angiographic findings of late hyperfluorescence, representing staining of the subretinal lesion and pooling of fluid in the subretinal space, may be seen in occult CNV. Idiopathic CNV, however, is more often classic and the yellow subretinal lesion would be unusual. The intraretinal hemorrhage, unilaterality and the angiographic pattern make the diagnosis of adult vitelliform dystrophy unlikely. This presentation, involving an acute and severe decrease in visual acuity in a young patient following a viral prodrome is suggestive of APMPPE; however the unifocality, unilaterality and presence of subretinal fluid and intraretinal hemorrhage in this case are not consistent with APMPPE.

Clinical Course

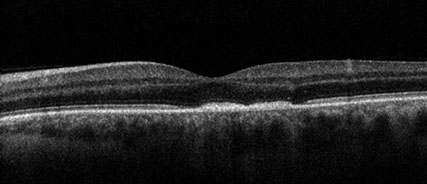

A conservative approach to management was taken and the patient was observed without treatment. One week after initial presentation, the visual acuity improved from 20/200 to 20/160 in the involved left eye. At that time, pigmentary alterations were evident in the macula; the yellow macular lesion had become less prominent; and the subretinal fluid had resolved completely (Figures 4A and B). Six week later, the visual acuity spontaneously improved to 20/25 and the macular lesion was nearly completely resolved (Figure 5).

Figures 4A and B: Color fundus photograph and spectral domain OCT, one week following the initial presentation. Note the color fundus photograph of the left eye reveals macular pigmentary alterations and a decrease in prominence of the yellow lesion. The SD-OCT reveals resolution of the submacular fluid but persistence of the outer retinal disturbance and RPE thickening.

Figures 5A and B: Color fundus photograph and spectral domain OCT, six weeks following the initial presentation. Note the yellow submacular lesion is nearly completely resolved and mild macular pigmentary alterations are present. SD-OCT reveals persistent RPE thickening and nearly complete resolution of the outer retinal disruption in the fovea.

Discussion

The clinical characteristics of this patient’s presentation are consistent with the diagnosis of unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy (UAIM). In 1991, Yannuzzi and colleagues published a case series of 9 patients, between 15 and 45 years of age, who presented with an acute onset of unilateral vision loss, which typically improved dramatically without treatment and was often preceded by a flu-like illness.1 Examination findings included a solitary area of irregular yellow or gray RPE thickening involving the central macula, associated with serous retinal detachment and, in some instances, intraretinal hemorrhage. Subsequent to the original publication, the clinical spectrum of this disease entity has expanded to include bilateral cases as well as the presence of papillitis and an association with pregnancy and human immunodeficiency virus.2

Fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are important adjuvant examinations in patients with UAIM. Fluorescein angiography may reveal irregular hyperfluorescence of the subretinal thickening in the early phase and nearly complete hyperfluorescence in the late phase.1 OCT often reveals an exudative detachment of the macula.3,4

The pathophysiology of UAIM likely involves an inflammation of the choroid, outer retina, and/or the retinal pigment epithelium.5 An inflammatory origin of UAIM is suggested by the occurrence, in many cases, of intraretinal hemorrhage and vitritis.1 The high incidence of an antecedent viral illness is indicative of an infectious etiology, which may, based on isolated case reports, represent coxsackievirus.6 Since bilateral cases can occur, this entity is more accurately known simply as, Acute Idiopathic Maculopathy, or AIM.

The natural history of AIM typically involves rapid and significant spontaneous improvement in visual acuity and clinical abnormalities.1 In addition, recurrence is rare.1 Therefore, management of these patients should be conservative and consist of observation to ensure that resolution occurs as expected. Because AIM may be easily confused with other diagnoses, including CNV, it is extremely important to maintain a high index of suspicion for UAIM in order to avoid unnecessary treatment.

Take Home Points

- AIM typically causes an acute onset of unilateral vision loss, which is often preceded by a flu-like illness.

- Examination findings include a subretinal lesion in the macula, which is often associated with subretinal fluid and intraretinal hemorrhage.

- Because UAIM usually resolves spontaneously, a high index of suspicion must be maintained in order to prevent unnecessary treatment.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Yannuzzi LA, Jampol LM, Rabb MF, et al. Unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1991;109(10):1411-6.

- Freund KB, Yannuzzi LA, Barile GR, et al. The expanding clinical spectrum of unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 1996;114(5): 555-9.

- Aggio FB, Farah ME, Meirelles RL, de Souza EC. STRATUSOCT and multifocal ERG in unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2006;244(4):510-6.

- Gupta A, Rogers S, Matthews BN. Unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93(8):1073-4.

- Haruta H, Sawa M, Saishin Y, et al. Clinical findings in unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy : New findings in acute idiopathic maculopathy. Int Ophthalmol 2009.

- Beck AP, Jampol LM, Glaser DA, Pollack JS. Is coxsackievirus the cause of unilateral acute idiopathic maculopathy? Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122(1):121-3.