West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

December, 2010

Presented by Jon Wender, MD

A 72-year-old African-American woman presented with a one-week history of blurred vision and pain in her right eye.

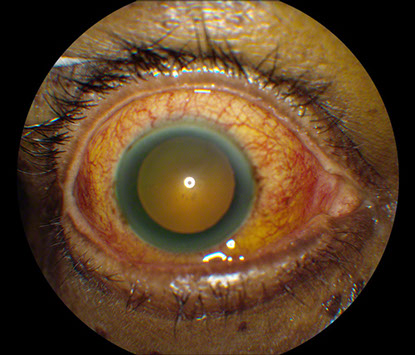

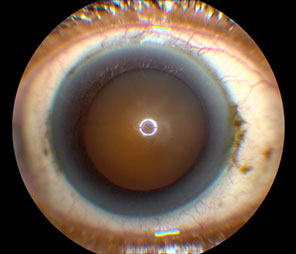

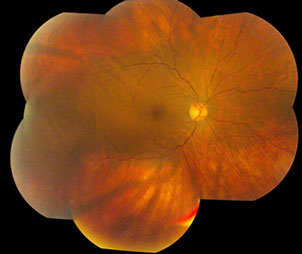

Figures 1A and B: External photograph of right eye demonstrating injection of the conjuctiva and deep episcleral vasculature. Fundus photograph montage of the right eye revealing tortuous retinal vessels and a large nonpigmented subretinal mass in the temporal quadrant of the eye.

Case History

A 72-year-old African-American woman presented with a one-week history of headache, blurred vision, redness, and tenderness of her right eye. Her past ocular history was non-contributory. The patient’s past medical history was remarkable for systemic hypertension and hypercholesterolemia and her medications included diltiazem, metoprolol, enalapril, hydrochlorothiazide and fluvastatin. Her family history was notable for open angle glaucoma in both of her parents. She denied any arthralgias or history of arthritis.

On examination, the best-corrected visual acuity was 20/32 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. The intraocular pressure was normal bilaterally. Anterior segment examination of the right eye was remarkable for severe diffuse conjunctival and deep episcleral injection and moderate anterior chamber reaction in the absence of keratic precipitates or iris nodules (Figure 1A). Posterior segment examination on the right revealed a clear vitreous cavity, a normal optic disc, tortuous retinal vessels, and a large, non-pigmented subretinal mass in the temporal mid-periphery and periphery associated with an overlying serous retinal detachment (Figure 1B). The examination of the left eye was unremarkable.

Differential Diagnosis

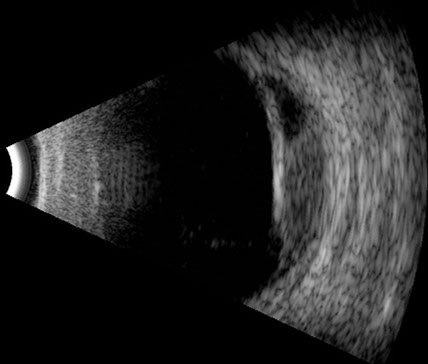

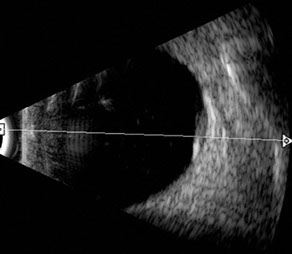

The differential diagnosis included amelanotic melanoma, choroidal hemangioma, choroidal metastasis, benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, and nodular posterior scleritis. B-scan and A-scan ultrasound revealed a dome-shaped subretinal mass with medium to high internal reflectivity, a small amount of fluid in Tenon’s space and an overlying serous retinal detachment (Figure 1C). Laboratory investigations, including P-ANCA, C-ANCA, rheumatoid factor, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) level, lysozyme, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS), rapid plasma regain (RPR), purified protein derivative (PPD) skin testing, and chest x-ray, were within normal limits. Renal failure was diagnosed, however, on the basis of albuminuria and hypokalemia. A renal biopsy was performed and revealed a thrombotic microangiopathy. Antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing was positive; double stranded DNA (ds-DNA) levels were elevated and the patient developed a butterfly rash on her cheeks, suggesting a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

What is your Diagnosis?

Figure 1C: Ultrasound of the right eye demonstrating a dome-shaped subretinal mass with an overlying serous retinal detachment and a small amount of fluid in Tenon’s space.

Clinical Course

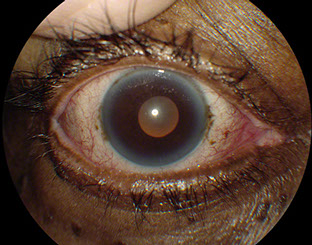

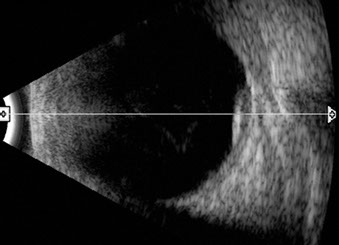

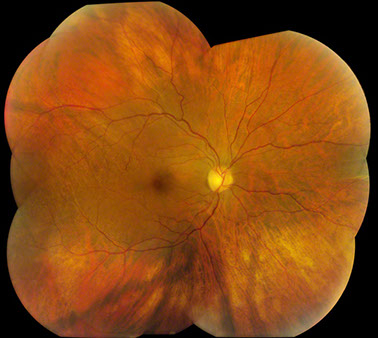

A posterior sub-Tenon’s injection of triamcinolone was performed and hourly treatment with topical prednisolone acetate 1% was initiated. Six weeks later, the visual acuity was 20/40, the conjunctival and deep episcleral injection had improved significantly (Figure 2A) and the size of the subretinal mass had decreased (Figure 2B). Ten weeks following initial presentation, the visual acuity remained stable, the anterior segment was quiet (Figure 3A), the size of the subretinal lesion had further declined and the retina was completely attached (Figure 3B and 3C). Fourteen weeks after presentation, the visual acuity was 20/32 and the subretinal mass was markedly smaller (Figure 4).

Figures 2A and B: External photograph and ultrasound of the right eye performed six weeks after the initial presentation. A marked improvement in the degree of conjunctival and episcleral injection was demonstrated and the size of the subretinal mass had decreased.

Figures 3A, B and C: External photograph, fundus photograph and ultrasound of the right eye performed 10 weeks after the initial presentation. The anterior segment was quiet, the size of the subretinal mass had decreased and the retinal detachment had resolved.

Figure 4: Fundus photograph taken 14 weeks after the initial presentation revealed that the subretinal mass had undergone a substantial reduction in size.

Discussion

Posterior scleritis can cause mild to severe inflammation that primarily involves the postequatorial portion of the sclera.1 It tends to affect adults more frequently than children and women more commonly than men.2

Clinical manifestations of posterior scleritis include proptosis, intraocular inflammation, optic disc edema, exudative retinal detachment, multifocal subretinal white lesions, cystoid macular edema (CME), uveal effusion, and an elevated subretinal mass, as seen in the present case.2, 3 Although the inflammation can be limited to the posterior sclera, the majority of patients also develop anterior segment inflammation. Anterior involvement is more common in the presence of systemic disease.2 Nodular posterior scleritis may mimic malignant melanoma, particularly in the absence of ocular pain, redness, and inflammation.4, 5

Ancillary imaging is often useful in the diagnosis of posterior scleritis and in ruling out diseases that may simulate posterior scleritis. Fluorescein angiography may demonstrate chorioretinal folds and vascular staining in addition to multiple pinpoint areas of leakage at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in the region of a serous retinal detachment. Other entities, such as Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease, malignant melanoma, and metastases, may also be associated with this type of leakage pattern. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, however, is a bilateral process that is not associated with a subretinal mass. Choroidal melanomas can be distinguished from posterior scleritis by ultrasound.

B-scan ultrasound in posterior scleritis may demonstrate a “T-sign” correlating with an echolucent area caused by fluid in Tenon’s space, and A-scan typically reveals high internal reflectivity associated with scleral thickening in cases of nodular posterior scleritis.3 Malignant choroidal melanomas, in contrast, tend to be associated with low to medium internal reflectivity.

Approximately 30% of patients with posterior scleritis are found to have an associated systemic disease.2 Systemic disease is more likely to be present in patients over the age of 50 years and in those with concurrent anterior inflammation. Systemic associations with posterior scleritis include rheumatoid arthritis, Wegener granulomatosis, polyarteritis nodosa, relapsing polychondritis, VKH disease, sarcoidosis, lymphoma, and SLE.2,6

The treatment of posterior scleritis should address the underlying etiology, but often typically includes systemic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), systemic or periocular corticosteroids, and systemic non-corticosteroid immunosuppressive agents. A significant percentage of patients will respond to systemic NSAIDs alone but, if they do not, there is usually a dramatic response to systemic or posterior sub-Tenon’s corticosteroids. In severe or recalcitrant cases, it may be necessary to utilize a non-corticosteroid immunosuppressive agent, such as an anti-metabolite. It is important to rule out infection prior to initiating treatment with systemic or periocular immunosuppressive agents.

Complications of posterior scleritis include uveitis, cataract, retinal detachment, scleral thinning, as well as recurrence of inflammation after discontinuation of therapy. Vision loss may occur in any patient with posterior scleritis, but the risk is greater if corticosteroids or non-corticosteroid immunosuppressive agents are required in order to control the inflammation.2 The visual prognosis tends to be worse with greater severity and longer duration of disease.1

Take Home Points

- Clinical manifestations of posterior scleritis include ocular pain and tenderness, serous retinal detachment, optic disc edema, multifocal subretinal lesions, CME, and an elevated subretinal mass. Anterior involvement is present in most, but not all, cases.

- B-scan ultrasonography often reveals a highly echogenic subretinal lesion caused by scleral thickening as well as fluid in Tenon’s space that, when present adjacent to the optic nerve, produces a T-sign.

- Fluorescein angiography may demonstrate multifocal pinpoint leaks at the level of the RPE.

- Nodular posterior scleritis may mimic uveal tumors, including choroidal melanoma, choroidal hemangioma, and choroidal metastasis.

- The treatment of posterior scleritis generally involves systemic NSAIDs, systemic or periocular corticosteroids or, less commonly, non-corticosteroid immunosuppressive agents.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Guyer DR, Yannuzzi LA, Chang S, Shields JA, Green WR. Retina-Vitreous-Macula, 1 ed: W.B. Saunders, 1999.

- McCluskey PJ, Watson PG, Lightman S, et al. Posterior scleritis: clinical features, systemic associations, and outcome in a large series of patients. Ophthalmology 1999;106(12):2380-6.

- Gass JD. Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular Disease, 4 ed: Mosby-Year, 1998.

- Arevalo JF, Shields CL, Shields JA. Giant nodular posterior scleritis simulating choroidal melanoma and birdshot retinochoroidopathy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2003;34(5):403-5.

- Demirci H, Shields C, Honavar SG, et al. Long-term follow-up of giant nodular posterior scleritis simulating choroidal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2000;118(9):1290-2.

- Wong R, Chan A, Johnson RN, McDonald HR, Kumar A, Gariano R, Cunningham ET. Posterior Scleritis in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Retinal Cases and Brief Reports 2010;4(4):326-31.