West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

February, 2011

Presented by Jon Wender, MD

A 23-year-old Asian woman presented with photopsias in her right eye.

Figure 1: Color fundus montage of the right eye reveals an orange-red retinal tumor in the temporal mid-periphery associated with a dilated, tortuous feeder arteriole, draining vein and macular exudation.

Case History

A 23-year-old Asian woman complained of intermittent photopsias in her right eye. Her past ocular history was significant for myopia. Her past medical history was notable for asthma and hypertension, which was not significant enough to necessitate medical therapy. The patient’s medications included Advair and NuvaRing for contraception. Her family history was notable for “organ cysts” in her mother and sister.

On examination, the visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye and the intraocular pressure was normal bilaterally. Her blood pressure was 136/104 mm Hg. The anterior segment examination was normal in each eye. The dilated fundus examination of the right eye revealed clear media, a normal optic disc, and a solitary red-orange mass, 2.5mm in diameter, in the temporal mid-periphery associated with dilated feeder and drainage vessels as well as intraretinal exudates in the superior macula (Figure 1). Dilated fundus examination of the left eye was within normal limits.

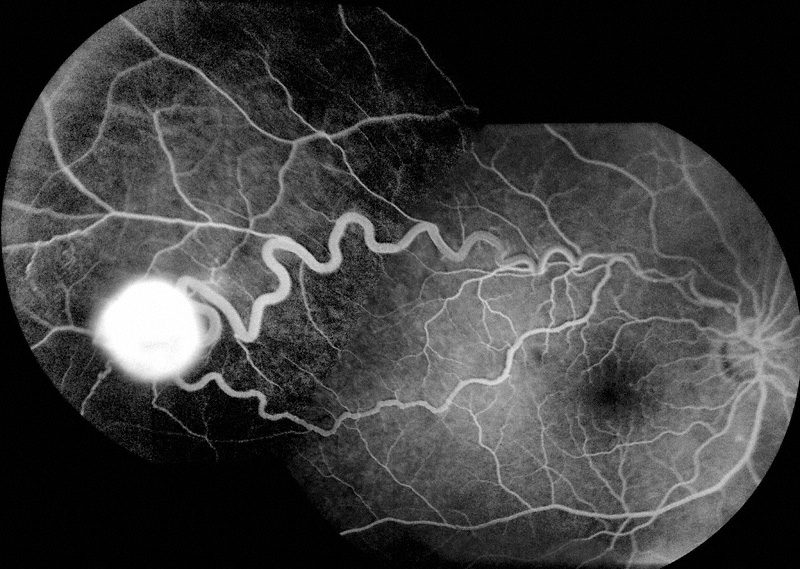

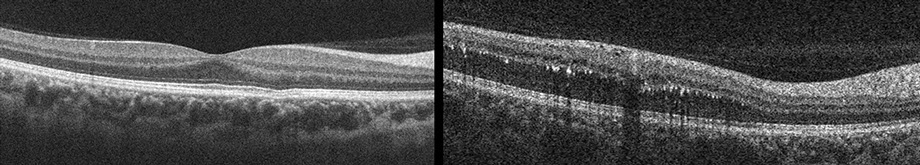

The late phase of the fluorescein angiogram (FA) of the right eye was significant for intense hyperfluorescence and leakage from the tumor (Figure 2). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) demonstrated a normal foveal depression and a small amount of intraretinal fluid and exudate in the superior macula (Figures 3A and B).

Figure 2: Montage of the late phase of the fluorescein angiogram of the right eye demonstrates bright hyperfluorescence and leakage from the vascular tumor.

Figures 3: Spectral domain optical coherence tomography of the right macula reveals a normal foveal depression (left image) and the absence of intraretinal or subretinal fluid in the fovea. The scan on the right shows retinal thickening and intraretinal exudates in the superior portion of the right macula.

What is your Diagnosis?

Diagnosis

The examination and fluorescein angiographic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of retinal capillary hemangioma. The patient was referred to her internal medicine physician for genetic testing and workup for the associated systemic manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease.

Discussion

Retinal capillary hemangiomas are rare, benign vascular tumors of the retina or optic disc and are often the presenting manifestation of von Hippel-Lindau disease.1 Von Hippel-Lindau disease is an uncommon systemic disorder that is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. The systemic manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease include pheochromocytoma, pancreatic cysts, renal cysts, central nervous system hemangioma, and renal cell carcinoma, which is the most common cause of mortality in patients with this disease.2 Patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease tend to develop retinal capillary hemangiomas at a much earlier age than patients who do not have the disease.3 In addition, the presence of multiple or bilateral retinal capillary hemangiomas is suggestive of von Hippel-Lindau disease.1

The retinal capillary hemangioma typically manifests as an orange-red fundus mass of widely variable size that is associated with dilated feeder or “twin” vessels.1 The tumor may be located in the peripapillary region or in the retinal periphery. Retinal capillary hemangiomas may cause vision loss by the accumulation of subretinal fluid or exudation in the macula or by the formation of a tractional retinal detachment or an epiretinal membrane.1

The differential diagnosis includes entities that share some clinical characteristics with retinal capillary hemangiomas, but none that possess all of the classic findings described above. Vasoproliferative tumors are retinal vascular lesions that may be associated with retinitis pigmentosa, uveitis, or long-standing retinal detachment. Vasoproliferative tumors, however, are not accompanied by dilated feeder vessels and they tend to occur in patients who are older than those with retinal capillary hemangiomas.2 Retinal cavernous hemangiomas are tumors manifested by a cluster of abnormal dilated vessels but, unlike retinal capillary hemangiomas, they lack feeder vessels and they do not tend to cause exudation. Wyburn-Mason disease is associated with dilated and tortuous retinal vessels but without an intervening hemangioma and exudation. Retinal capillary hemangiomas involving the optic disc may mimic papilledema or papillitis.

Although retinal capillary hemangiomas are typically diagnosed by clinical examination alone, a variety of ancillary tests, including FA and ultrasound, may assist in making the diagnosis. Fluorescein angiography reveals hyperfluorescence of the feeder retinal arteriole in the early phase, filling of the capillaries intrinsic to the vascular mass in the mid-phase, and homogeneous bright hyperfluorescence and leakage from the tumor in the late phase. Ultrasound, which can be useful in evaluating lesions that are greater than 1 to 2 millimeters in thickness, may reveal a well-demarcated mass with high internal reflectivity and the absence of choroidal involvement.1

Genetic testing for von Hippel-Lindau disease is nearly 100% accurate and is essential in evaluating and counseling patients.4 The gene that is affected in von Hippel-Lindau disease is a tumor suppressor gene that is located on chromosome 3. Damage to this gene leads to abnormal degradation of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF). The presence of HIF results in elevated levels of various mediators, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), that lead to vascular proliferation even in the absence of hypoxic conditions.5

A systemic evaluation for the common manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease should be performed in all patients and family members in whom genetic testing is positive.2 General guidelines indicate that the following examinations should be performed on an annual basis: physical examination, dilated fundus examination, urinalysis, 24-hour urine collection to assess vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) levels to rule out pheochromocytoma, as well as abdominal ultrasound to rule out renal cell carcinoma.1 It is recommended that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain to rule out central nervous system hemangioblastoma, and computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen to rule out renal cell carcinoma and pheochromocytoma be performed every three years.1

Indications for the treatment of retinal capillary hemangiomas are not well established. Some physicians recommend treating all patients with retinal capillary hemangiomas because they usually enlarge over time and ultimately result in vision loss.2 Some retinal capillary hemangiomas, however, remain stable or even regress over time, prompting some specialists to recommend observation unless the following features are present: visual symptoms, large tumor size, tumor location near the macula, subretinal fluid, or progression in size or associated findings.

There are a variety of options for the treatment of retinal capillary hemangiomas. Laser photocoagulation may be indicated for smaller tumors that are located in the posterior pole and not associated with a significant amount of subretinal fluid.1 Laser can be used to occlude the feeder vessels, in which case multiple sessions of treatment are typically required. In the case of smaller lesions, however, laser can be applied directly to the tumor, in which case fewer treatments are generally necessary.2 The triple freeze-thaw cryotherapy approach may be preferable for larger tumors, particularly those located in the retinal periphery and those associated with a significant amount of subretinal fluid.

Other treatment approaches have also been implemented with varying degrees of success. Plaque or external beam radiation may rarely be used to treat tumors that are too large to be treated with cryotherapy.1 Some newer treatments include photodynamic therapy6 and intravitreal anti-VEGF agents,5 but extensive experience is not available to date. Pars plana vitrectomy may be required in some cases to repair tractional or rhegmatogenous retinal detachment or to remove an epiretinal membrane.7 Enucleation may rarely be required in the presence of intractable pain related to neovascular glaucoma.2

The goal of treatment of retinal capillary hemangiomas is to reduce the amount of subretinal fluid and exudation. Scarring and a decrease in the size of the tumor or the feeder vessels may also occur as a result of treatment. The response to therapy is typically gradual and treatment may be repeated in 1 to 2 months if the initial response is inadequate. Complications of treatment include vitreous hemorrhage as well as an increase in the amount of subretinal fluid.

The visual prognosis for patients with retinal capillary hemangiomas is variable and dependent on a variety of factors. In general, visual prognosis is worse in the presence of visual symptoms, greater tumor size, tumors located near the macula, and the presence of subretinal fluid or macular fibrosis. Vision loss becomes more likely with increasing age. A permanent decrease of visual acuity to a level less than 20/40 occurs in roughly 25% of eyes.2 Regarding systemic prognosis, the median survival of patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease is 49 years.1 Genetic counseling is strongly recommended for all patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease, as the disease is transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion with a very high penetrance.2

Take Home Points

- Retinal capillary hemangiomas are benign vascular tumors of the retina or optic nerve that are commonly associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease.

- von Hippel-Lindau disease is a rare, autosomal dominantly inherited disorder, which is associated with a defect on chromosome 3.

- Annual screening is recommended for all patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease in order to detect the systemic manifestations. These manifestations include central nervous system hemangiomas, pheochromocytoma, pancreatic and renal cysts, and renal cell carcinoma, which is the most frequent cause of death among patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease.

- Characteristic examination findings of retinal capillary hemangiomas include dilated feeder vessels and an orange-red mass that may be associated with subretinal fluid, exudation, or vitreoretinal fibrovascular proliferation.

- There are a variety of treatment options, including laser photocoagulation, cryotherapy, radiation, photodynamic therapy, and intravitreal anti-VEGF agents, for patients with retinal capillary hemangiomas. The indications for treatment are not well established.

- The visual prognosis for patients with retinal capillary hemangiomas is variable and is generally worse in the presence of visual symptoms, larger tumor size, tumors located in the macula, and the presence of submacular fluid or tractional retinal detachment.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Shields C. Retinal Capillary Hemangioma. In: Guyer D, ed. Retina-Vitreous-Macula. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1999; v. 2.

- Magee MA, Kroll AJ, Lou PL, Ryan EA. Retinal capillary hemangiomas and von Hippel-Lindau disease. Semin Ophthalmol 2006;21(3):143-50.

- Singh AD, Nouri M, Shields CL, et al. Retinal capillary hemangioma: a comparison of sporadic cases and cases associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Ophthalmology 2001;108(10):1907-11.

- Singh AD, Shields CL, Shields JA. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Surv Ophthalmol 2001;46(2):117-42.

- Wong WT, Chew EY. Ocular von Hippel-Lindau disease: clinical update and emerging treatments. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2008;19(3):213-7.

- Sachdeva R, Dadgostar H, Kaiser PK, et al. Verteporfin photodynamic therapy of six eyes with retinal capillary haemangioma. Acta Ophthalmol;88(8):e334-40.

- McDonald HR, Schatz H, Johnson RN, et al. Vitrectomy in eyes with peripheral retinal angioma associated with traction macular detachment. Ophthalmology 1996;103(2):329-35 ; discussion 34-5.