West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

February, 2012

A 48-year-old man with progressive loss of central vision.

Presented by Sandeep Randhawa, MD

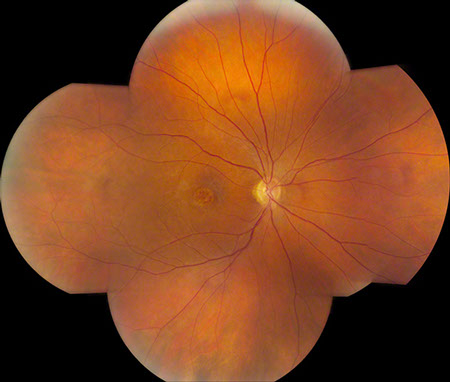

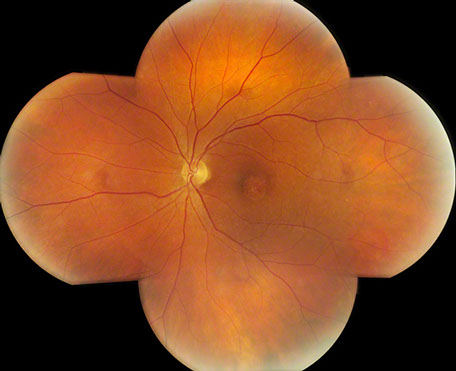

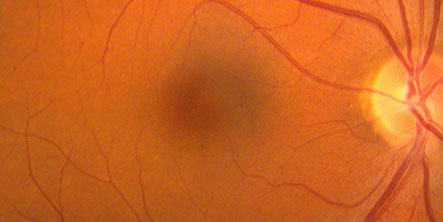

Figures 1: Color photo montage of the right and left eye. Note the sharply demarcated area of macular atrophy in each eye.

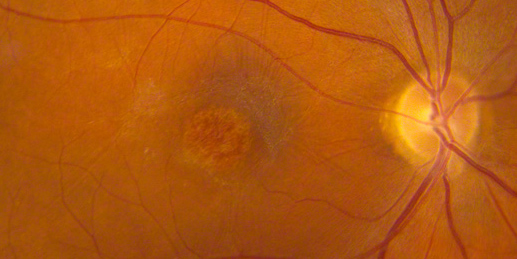

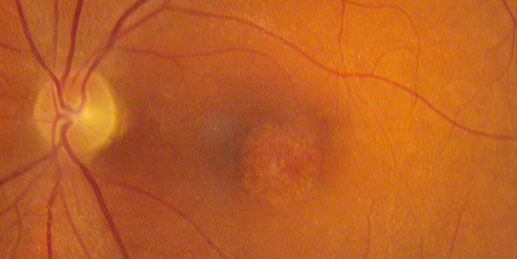

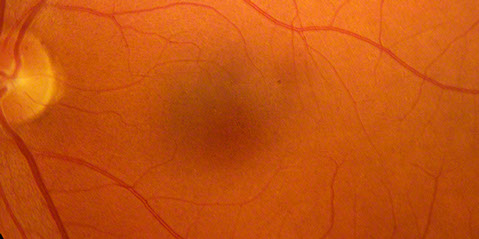

Figures 2: Color photos of the right and left macula showing detailed view of the distinct area of atrophy.

Case History

A 48-year-old Caucasian man presented with a gradual decline in central vision in both eyes over seven years. In a previous visit three years prior, his visual acuity was 20/40 in the right eye and 20/70 in the left eye. His past medical history was unremarkable. Family history was significant for legal blindness in his mother when she was in her mid-forties.

On examination his visual acuity was 20/200 in both eyes. Intraocular pressure and slit lamp examination of the anterior segment were normal in both eyes. Fundus examination revealed a demarcated area of macular atrophy in both eyes (Figures 1 and 2). The macula had been documented as normal on the eye exam seven years prior when the patient had the onset of symptoms (Figure 3).

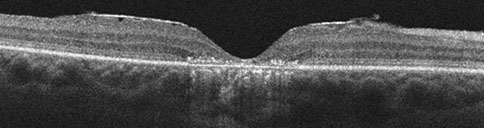

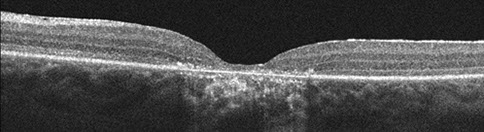

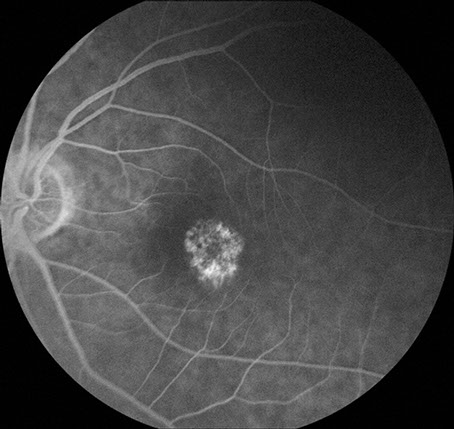

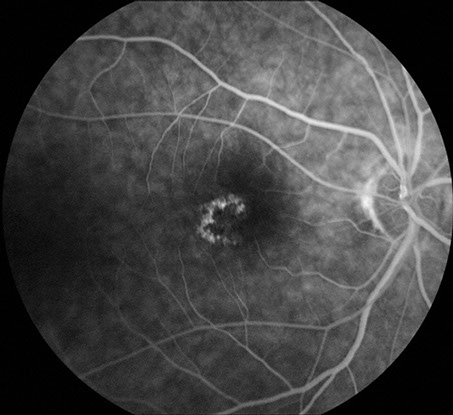

Visual field testing revealed a moderate central scotoma both eyes. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed bilateral loss of the photoreceptor inner segment-outer segment layer and the underlying retinal pigment epithelium (Figure 4). Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) showed bilateral hypoautofluoresecence in the area of the lesions suggestive of devitalized retinal pigment epithelium (Figure 5). Fluorescein angiography revealed a window defect corresponding to the area of atrophy (Figure 6). Farnsworth-Munsell 100-hue test for color vision revealed generalized depression without a specific defect along a specific axis.

Figure 3: Color fundus photos of the right and left macula 7 years earlier. Each macula appeared normal despite vision of 20/40 in the right eye and 20/70 in the left eye

Figures 4: Horizontal SD-OCT scans through the right (top) and the left (bottom) macula. Atrophy of the outer retinal layers as well as the retinal pigment epithelium is present.

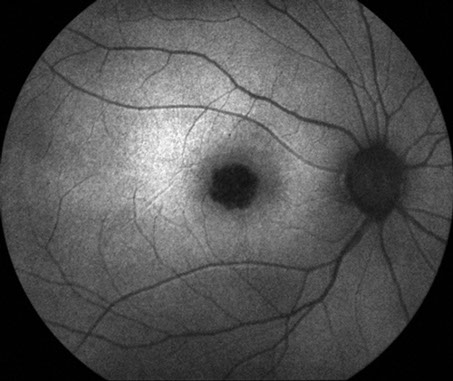

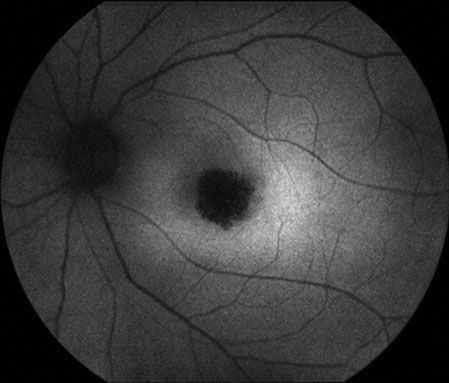

Figures 5: Fundus autofluorescence photos of the right and left eye. Note the hypoautofluorescence centered in each macula due to retinal pigment epithelial atrophy

Figures 6: Fluorescein angiogram of the right and left macula. Note the hyperfluorescent areas centrally corresponding to the area of retinal pigment epithelial atrophy.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis

Macular dystrophies that principally involve the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) include the following major clinical entities: fundus flavimaculatus-Stargardt’s disease (FF-STGD), central areolar pigment epithelial dystrophy, North Carolina dystrophy, familial or dominant drusen, vitelliform dystrophy (Best disease), pattern dystrophies, Sjogren’s reticular dystrophy of the RPE, and benign concentric annular dystrophy.1

Dystrophies of the RPE may also be classified into three morphological groups with some stage of eventual atrophy of the RPE common to all.2 The first group is characterized initially by predominantly whitish or yellowish lesions at the level of the RPE. Autosomal dominant drusen, FF-STGD, and vitelliform (Best disease) dystrophy fall into this category. North Carolina macular dystrophy is also characterized by yellow drusen like lesions in its initial stages which can progress to macular disciform scarring.

The second group is notable for hyperpigmented RPE lesions and can be associated with autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, as well as uncertain modes of inheritance. Sjogren’s reticular dystrophy is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern while fundus pulverulentus and the pattern dystrophies are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.

In the third morphological group, the RPE is atrophic with absent yellow, white or pigmented lesions. Central areolar pigment epithelial dystrophy and benign concentric annular dystrophy are included in this category. Patients with benign concentric annular dystrophy initially present with a of depigmentation in a bull’s eye pattern around the fovea and do not experience a significant loss of visual acuity in the initial stages.3

In our patient, the adulthood onset, gradually progressive visual decline, symmetric circumscribed area of macular geographic atrophy (confirmed to involve the RPE on OCT), were clinical characteristics most consistent with central areolar pigment epithelial dystrophy (CAPED).

Additional History

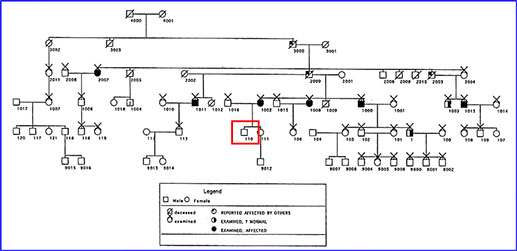

Electrophysiologic testing (ERG) revealed a normal maximal combined response and suboptimal cone function (decreased amplitude on the photopic ERG and delayed implicit time on the 30 Hz flicker, Figure 7). The patient was eventually found to be a descendant of pedigree, published as central areolar pigment epithelial dystrophy.4 The patient was asymptomatic at the time of that publication, and was listed as an unaffected member (Figure 8, patient highlighted).4

Figure 8: The patient’s pedigree as published in Ophthalmology in 1996 (the patient is outlined in red and was unaffected when first examined)

Figure 7: Electrophysiologic testing (ERG) revealing a normal maximal combined response and suboptimal cone function (decreased amplitude on the scotopic ERG and delayed implicit time on the 30 Hz flicker)

Discussion

Central areolar pigment epithelial dystrophy as described by Gass is an autosomal dominant macular dystrophy that is characterized by the development of fine mottled depigmented RPE in the macular region in late childhood or adulthood which may be asymptomatic at onset.5 Progressive symmetric round areas of geographic atrophy of the macular RPE without flecks or drusen develop gradually with visual decline to 20/200. Associated findings include a central scotoma with normal peripheral fields. Fluorescein angiography reveals RPE transmission defects corresponding to the punctate and confluent lesions within the fovea.

Keithahn4 et al. described a large family with central areolar pigment epithelial dystrophy with autosomal dominant inheritance and variable expression. None of the patients had flecks, drusen, or peripheral retinal abnormalities. Early in the disease course, electrophysiologic findings are normal but may deteriorate with progressive rod and cone dysfunction.4

Take Home Points

- Macular dystrophies include many diseases that primarily affect but are not limited to the macula. Inheritance patterns may vary, and complete examination with fundus autofluorescence, optical coherence tomography, fluorescein angiography, and electrophysiology aid in accurate diagnosis.

- In all macular dystrophies, pedigree analysis and examination of affected members is essential. Genetic testing can be offered for many macular dystrophies.

- Central areolar pigment epithelial dystrophy (CAPED) presents in an autosomal dominant fashion with initially fine mottled circumscribed depigmented retinal pigment epithelial lesions in the macula that progress to larger atrophic areas and visual deterioration.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Fu AD, Ai E, McDonald HR, Johnson RN, Jumper JM. Hereditary Macular Dystrophies. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, eds. Duane’s Clinical Ophthalmology, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2005;9:1-40.

- O'Donnell FE, Schatz H, Reid P, Green WR. Autosomal dominant dystrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979 Apr;97(4):680-3.

- BJ Klevering, JJC Van Lith-Verhoevn, CB Hoyng. Macular Dystrophies. Clinical Findings and genetic Aspects. medical Retina, Eds FG Holtz, RF Spaide. Springer 2005

- Keithahn MA, Huang M, Keltner JL, Small KW, Morse LS. The variable expressivity of a family with central areolar pigment epithelial dystrophy. Ophthalmology. 1996 Mar;103(3):406-15.

- Gass JDM. Stereoscopic atlas of macular diseases: diagnosis and treatment, 3rd ed. Vol. 1. St. Louis: Mosby, 1987; 98-99, 256-265.