West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

Feb, 2014

Presented by Steven Williams, MD

A 57 year-old woman with decreased vision and hearing loss following a viral illness

A

B

C

D

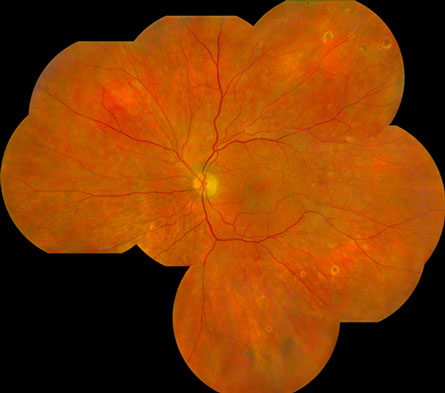

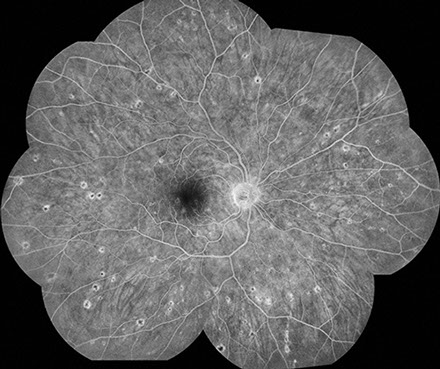

Figures 1A-D: Posterior pole (A-B) and montage (C-D) photographs reveals scattered yellow-white, ovoid chorioretinal lesions bilaterally. They are most readily visible in the midperiphery than in the macula and have an atrophic appearance.

Case History

A 57 year-old Caucasian woman presented with persistent blurry central vision in the left eye 6 weeks after an acute viral illness. She initially reported symptoms of severe headache, fever, vomiting and diarrhea for several days while caring for her mother who was recovering from a viral illness. She also complained of photophobia. Past medical history was notable for myasthenia gravis for which she had a thymoma resection and was taking 100mg of azathioprine daily and 5mg of oral prednisone every other day.

An initial medical work-up, including lumbar puncture with cerebrospinal fluid analysis and brain MRI, was significant only for possible pyelonephritis and she was treated with oral ciprofloxacin. She continued to decline clinically and required hospitalization during which time she developed progressive hearing loss and progressive flaccid paralysis of all four extremities, without involvement of the respiratory musculature.

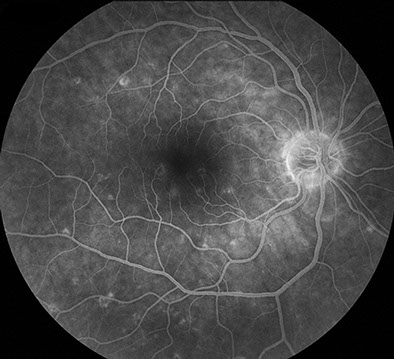

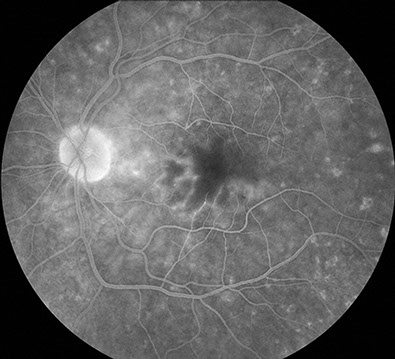

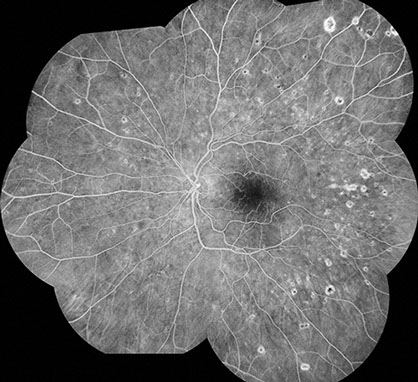

On examination 6 weeks after hospitalization, vision was 20/30 in the right eye and 20/250 in the left eye. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable bilaterally. The vitreous was clear in both eyes. Posterior segment examination showed scattered, chorioretinal lesions in the macula and mid-peripheral retina bilaterally, approximately 200-300 microns in size, with peripheral chorioretinal atrophy and central pigmentation (Figure 1A-D). Fluorescein angiography showed normal artero-venous transit in the right eye. There was mild disc hyperemia and prominent staining of the chorioretinal lesions bilaterally. There was also an occlusive vasculitis in the left eye, affecting both arterioles and veins, with associated capillary non-perfusion in the macula resulting in an enlarged foveal avascular zone (Figure 2A-D). The chorioretinal lesions were more apparent on fluorescein angiography.

A

B

C

D

Figures 2A-D: Flourescein angiography of the posterior pole (A-B) and periphery (C-D) reveals staining of the chorioretinal lesions bilaterally. Late frames also shows vasculitis associated with capillary nonperfusion in the macula of left eye.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for an occlusive vasculitis with bilateral retinochoroiditis includes; infectious diseases such as syphilis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis, herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, varicella zoster virus, West Nile virus, and Rift Valley fever; and inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis, Behcet’s disease, multifocal choroiditis and birdshot chorioretinitis. Less likely entities on the differential include Coccidioides, presumed ocular histoplasmosis, choroidal metastasis and primary intraocular lymphoma.

Our patient received a repeat lumbar puncture during her hospitalization, which demonstrated pleocytosis with polymorphonuclear cell predominance, elevated protein, and low glucose. Cerebrospinal fluid was positive for West Nile virus IgG and IgM. Audiography demonstrated moderate sensorineural hearing loss. Nerve-conduction studies were also consistent with West Nile virus associated paralysis.

Fig. 2A-D: Flourescein angiography of the posterior pole (A-B) and periphery (C-D) reveals staining of the chorioretinal lesions bilaterally. Late frames also shows vasculitis associated with capillary nonperfusion in the macula of left eye.

Clinical Course

Our patient required a 5 day ICU stay and showed gradual improvement in her hearing and motor function with supportive care. Her mother also had a diagnosis of West Nile virus. This is the first reported case of WNV associated with profound hearing loss.

Discussion

West Nile virus (WNV) is an RNA arbovirus in the Flaviviridae family, which includes Japanese encephalitis, yellow fever, and dengue viruses. It was first identified in Uganda in 1937 and since the 1990s there have been numerous outbreaks in countries all over the world, including Algeria, Romania, Russia, Israel and the United States. It is now endemic in many parts of the world. In 2012, 5674 cases of WNV were reported to the Centers for Disease Control, occurring in all 48 states within the continental US, and resulting in 286 deaths. The highest incidence of WNV was in 2003, when there were 9862 cases, resulting in 264 deaths in the US.

The female Culex mosquito, which feeds on the blood of infected birds, acts as a vector of incidental disease transmission to many other species, including horses, dogs, cats and humans. Humans, like many other non-bird species are not part of the transmission cycle Although levels of viremia are typically too low to permit human to human transmission, there have been reports of transmission via blood transfusion and organ transplantation. The incubation period is 2-14 days. Commonly the virus results in rapid onset of a high grade fever (>39 degrees centigrade), headache, myalgias and gastrointestinal symptoms. The symptoms are usually self-limited and resolve in less that one week. Although most WNV cases are asymptomatic, it can result in meningoencephalitis in approximately 30-50% of symptomatic cases, with associated proximal muscle weakness, movement disorders, paralysis, respiratory failure, mental status changes, coma or death.

Khairallah et al reported a series of 29 consecutive patients with WNV with ocular involvment. Ocular manifestations of the disease typically included ovoid multifocal chorioretinal lesions 100-1500 µm in size, which can be scattered throughout the periphery or grouped in linear arrays. Active chorioretinal lesions were circular, deep, and creamy in appearance. They demonstrated early hypofluoresence and late staining on fluorescein angiography. Inactive lesions were partially atrophic, partially pigmented, with central hypofluoresence and peripheral hyperfluoresence. Lesions were more prominent in the mid-periphery but were present in the posterior pole in 66% of eyes. In a series of 14 eyes (7 patients), Chan et al reported retinal vasculitis in 29%, with occlusive vasculitis in 14%. Similarly, a case series published by Garg et al reported occlusive vasculitis in 22%. Other ocular manifestations include anterior uveitis (early finding), uveitis without chorioretinitis, retinal hemorrhage and optic neuropathy. Several case series have demonstrated a high incidence of concomitant diabetes mellitus. Central vision was usually preserved.

Diagnosis is accomplished by serologic testing of blood serum or cerebrospinal fluid for WNV IgM and IgG. Cerebrospinal fluid studies typically show pleocytosis, neutrophilia, elevated protein level, reference glucose and lactic acid levels and no erythrocytes. Seroconversion may take up to 8 days after the onset of symptoms and lab tests should be repeated 2-3 weeks later. Cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses is also common. Treatment is mainly supportive.

Take Home Points

- West Nile virus is a potential cause of bilateral multifocal chorioretinitis and vasculitis.

- The disease is usually self-limited but can result in meningoencephalitis and death.

- West Nile virus is transmitted by infected mosquitoes, and appropriate precautions should be made for people living in endemic areas.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Chan CK, Limstrom SA, Tarasewicz DG, Lin SG. Ocular Features of West Nile Virus Infection in North America: A study of 14 eyes. Ophthalmology 2006 Sep;113:1539-46.

- Davis LE, DeBiasi R, Goade DE, et al. West Nile virus neuroinvasive disease. Ann Neurol 2006;60:286–300.

- Gea-Banacloche J, Johnson RT, Bagic A, Butman JA, Murray PR, Agarwal AG. West Nile virus: pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:545-53.

- Garg S, Lee JM. Systemic and Intraocular Manifestations of West Nile Virus Infection. Surv Ophthalmol 2005;50:1-13.

- Iwamoto M, Jernigan DB, Guasch A, et al: Transmission of West Nile virus from an organ donor to four transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2196–203.

- Khairallah M, Ben Yahia S, Ladjima L, et al. Chorioretinal involvement in patients with West Nile virus infection. Ophthalmology 2004;111:2065–70.

- Lindsey NP, Lehman JA, Staples E. CDC. West Nile Virus and Other Arboviral Disease- United States, 2012. MMWR, 2013;62:513-517.

- McBride W, Kill KR, Wiviott L. West Nile Virus infection with hearing loss. J Infect 2006; 53:e203-5.

- Papa A, Karabaxoglou D, Kansouzidou A. Acute West Nile virus neuroinvasive infections: cross-reactivity with dengue virus and tick-borne encephalitis virus. J Med Virol 2011;83:1861–5.

- Tyler KL, Pape J, Goody RJ, Corkill M, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. CSF findings in 250 patients with serologically confirmed West Nile virus meningitis and encephalitis. Neurology 2006;66:361–5.