West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

February, 2015

A 68-year-old Caucasian woman presented with bilateral peripheral scotomas

Presented by Aileen Sy, MD

and Steven Williams, MD

Figures 1: Color fundus photograph montages of the right and left eye. Note the bilateral arteriolar sheathing. An acute branch retinal arteriolar occlusion (BRAO) involving the superotemporal arcade vessel is present in the left eye.

Case History

A 68-year-old Caucasian woman presented with bilateral peripheral scotomas. She reported having two episodes of acute onset peripheral visual field loss over a one month period, first in the right eye and then in the left eye. Visual symptoms were accompanied by transient buzzing in her ears bilaterally. Past ocular and medical histories were otherwise unremarkable. She did not take any medications and was allergic to penicillin. Her family history was remarkable for age-related macular degeneration in her mother.

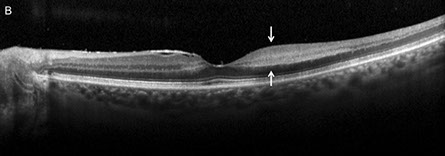

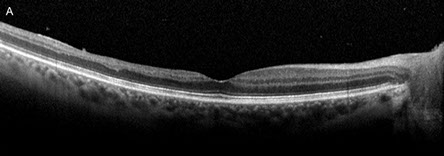

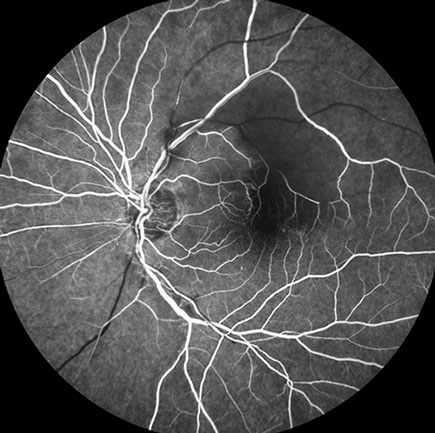

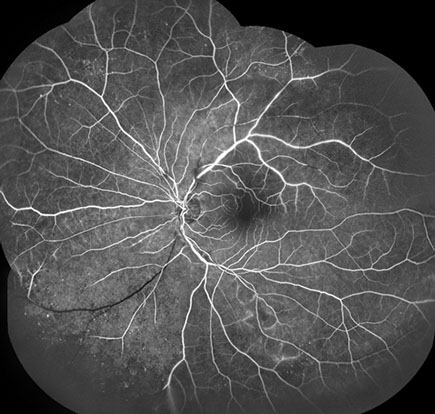

On examination, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/25 in the right eye and 20/32 in the left eye. Intraocular pressures were normal. Gonioscopy showed the angel to be open bilaterally. Anterior segment examination revealed mild nuclear sclerosis, but was otherwise unremarkable. Posterior segment examination was notable for scattered areas of arteriolar sheathing involving the arcade vessels of each eye, and for an acute BRAO involving the superior arcade vessels on the left (Figs 1). SD-OCT imaging through the fovea of each eye revealed inner retinal thinning temporally in the distribution of a prior BRAO, now re-cannalized, on the right (Fig. 2A) and inner retinal (GCL, IPL, INL) hyper-reflectivity in the distribution of the acute BRAO on the left (Fig. 2B). A mild epiretinal membrane was present bilaterally. Fluorescein angiography demonstrated delayed or absent arterial perfusion in the distribution of prior or acute BRAOs (Figs. 3) Perivascular leakage and staining consistent with vasculitis was also present bilaterally. Late frames revealed widespread areas of peripheral retinal nonperfusion in each eye.

Figures 2: Horizontal SD-OCT images through the fovea of each eye revealed inner retinal thinning temporally in the distribution of a prior BRAO, now re-cannalized, on the right (A) and inner retinal (GCL, IPL, INL) hyper-reflectivity in the distribution of the acute BRAO in the left eye (white arrows, Fig 2B). Mild epiretinal membrane formation was present bilaterally.

A

B

D

C

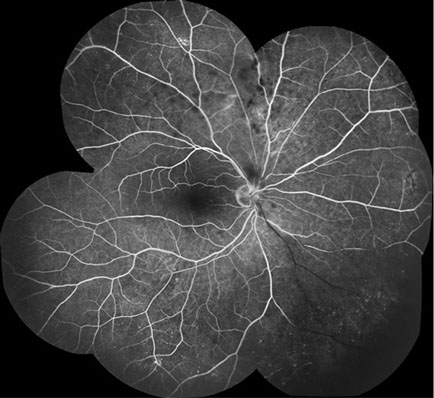

Figures 3: Fluorescein angiography demonstrated delayed or absent arterial perfusion in the distribution of old (A, C and D) and recent acute branch retinal artery occlusions (A and B). Perivascular leakage and staining consistent with vasculitis was also present bilaterally (B,C and D). Late frames revealed widespread areas of peripheral retinal nonperfusion in each eye (C and D).

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for recurrent BRAO includes infectious diseases, such as toxoplasmosis, Bartonellosis, herpes virus infection (HSV, VZV, CMV), syphilis, rickettsiosis, West Nile virus, and Rift Valley fever, Lyme disease, and tuberculosis; and inflammatory conditions, such as sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematous (SLE), Behçet’s disease, and Susac's syndrome. Many cases of recurrent BRAO remain idiopathic despite thorough evaluation.

Discussion

The patient initially had an extensive and unrevealing work-up for embolic, inflammatory and coagulation disorders. An MRI of the brain showed a small infarction in the cerebellum without evidence of corpus callosum infarction, a characteristic finding of Susac’s syndrome. Formal audiology testing was not pursued. In subsequent months the patient developed gastro-intestinal symptoms and underwent an intestinal biopsy that revealed changes consistent with Crohn’s disease.

Crohn's disease, also known as regional ileocolitis, is a granulomatous, inflammatory bowel disease that typically affects young adults. Systemic manifestations include arthritis, anemia, hepatitis and erythema nodosum. Ocular complications are relatively uncommon (4-6% of cases), but include corneal infiltration and ulceration, episcleritis, scleritis, and anterior uveitis, which is typically nongranulomatous. Reported posterior segment complications include vitritis, macula edema, neuroretinitis, serous retinal detachment, retinal hemorrhages, and retinal vasculitis.1 Retinal vascular occlusion is uncommon in patients with Crohn’s disease, with only a few reported cases of CRAO, BRAO, and BRVO.2-6 Retinal vasculitis can be the initial manifestation of Crohn’s disease, but is rare.3,4

Branch retinal artery occlusion has been reported in a variety of infectious and inflammatory conditions. In a retrospective case series of 18 eyes, Kalhoun et al found that ocular toxoplasmosis was the most common uveitis-related cause of BRAO, followed by various infectious and non-infectious etiologies, including Crohn’s disease.6 In eyes with retinochoroiditis, BRAO is believed to be induced by perivascular inflammation, which leads to arterial contraction, increased blood viscosity, and arterial thrombosis.7,8 In cases where retinochoroiditis is absent, BRAO may be induced by infiltration of inflammatory cells into the wall of the artery, resulting in disruption of blood flow and arterial thrombosis.8

Branch retinal artery occlusion is a clinical diagnosis aided by multimodal imaging. Treatment of inflammatory, noninfectious BRAO consists of systemic corticosteroids in the acute setting, followed by long-term immunosuppressive therapy to prevent recurrence as indicated. While reperfusion of occluded arcade vessels is typical, inner retinal atrophy in the involved area results in persistent visual field defects in most cases.6 In contrast, peripheral arteriolar occlusion, while often asymptomatic, typically results in persistent non-perfusion, as in our case.

Clinical Follow-up

Our patient was treated with high dose corticosteroid therapy, followed by long-term immunosuppressive therapy and had no recurrence of retinal inflammation during the ensuing three years of follow up.

Take Home Points

• Recurrent BRAOs should prompt consideration of known infectious and non-infectious cases.

• Crohn’s disease is a rare cause of recurrent BRAO.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References:

- Agarwal A. Gass’ Atlas of Macula Diseases, 5th Ed. Elsevier; 2012. Pg. 1048.

- Duker JS, Brown GC, Brooks L. Retinal vasculitis in Crohn’s disease. Am J Ophthalmol 1987;103:664-8.

- Ruby AJ, Jampol LM. Crohn’s disease and retinal vascular disease. Am J Ophthalmol 1990;110:349-53.

- Abdul-Rahman, AM, Raj R. Bilateral retinal branch vascular occlusion- A first presentation of Crohn disease. Retinal Cases and Brief Reports 2010;4(2):102-4.

- Saatci OA, Koçak N, Durak I, Ergin MH. Unilateral retinal vasculitis, branch retinal artery occlusion and subsequent neovascularization in Crohn’s disease. Int Ophthalmol 2001;24:89-92.

- Kahloun R, Mbarek S, Khairallah-Ksiaa I, Jelliti B, et al. Branch retinal artery occlusion associated with posterior uveitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infec. 2013 Jan 21;3(1):16.

- Braunstein RA, Gass JDM. Branch artery obstruction caused by toxoplasmosis. Arch Ophthalmol 1980;98:512-3.

- Ormerod LD, Skolnick KA, Menosky MM, Pavan PR, Pon DM. Retinal and choroidal manifestations of cat-scratch disease. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1024-31.

- Cunningham ET Jr, Koehler, JE. Ocular bartonellosis. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 130:340-349.