West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

January, 2012

Presented by Paul Stewart, MD

A 59 year-old man with a two-month history of decreased vision in both eyes.

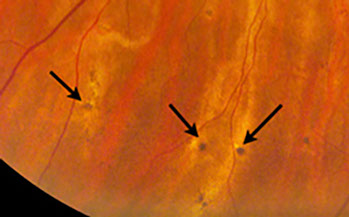

Figures 1: Color photo montage of the right eye showing optic disc pallor. The retinal vessels are attenuated and there is sclerosis of the cilioretinal artery along with multiple choroidal vessels. There are pigmentary changes in the periphery overlying choroidal vessels (see box and detail above (arrows) for expanded view). Note the focal area of RPE atrophy temporally.

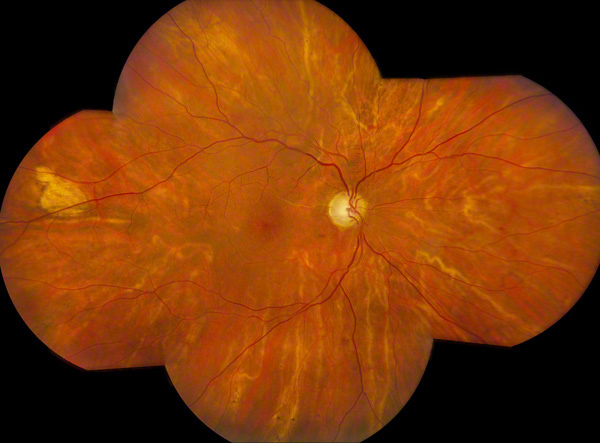

Figure 2: Color photo montage of the left eye shows a pink optic nerve with intact rim. The retinal vessels are attenuated and there are microvascular abnormalities in the posterior pole. There are scattered retinal hemorrhages. There is a sclerosed cilioretinal artery and multiple choroidal vessels appear sclerosed as well.

Case History

A 59 year-old man presented with a two-month history of painless, progressive loss of vision in both eyes, affecting his right eye more than his left. His past ocular history was unremarkable.

Examination revealed a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/200 in the right eye and 20/40 in the left eye. The intraocular pressures were normal and anterior segment examination was unremarkable. Confrontational visual field examination revealed a superonasal defect in the right eye and a superotemporal defect in the left eye.

Fundus examination of the right eye showed a pale optic disc, attenuated retinal vessels with arteriovenous crossing changes, and a sclerotic cilioretinal artery. Many choroidal vessels appeared whitish and sclerotic as well (Figure 1). In the periphery, there were pigmented spots with a rim of hypopigmentation and inferiorly there was an area of linear pigmentation overlying a choroidal vessel. A focal area of RPE atrophy was present in the temporal periphery.

Fundus examination of the left eye showed a normal optic disc, and attenuated retinal vessels with arteriovenous crossing changes. (Figure 2) In this eye as well, the cilioretinal artery appeared sclerotic. In the macula, multiple collateral vessels were present and there were scattered retinal hemorrhages most evident in the periphery. The choroidal vessels appeared similar to the right eye with many appearing sclerotic.

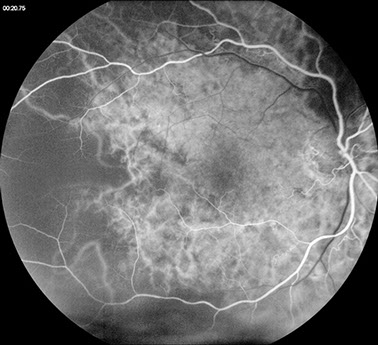

Fluorescein angiography of the right eye revealed choroidal ischemia. A large wedge-shaped area temporally in the right eye showed very delayed choroidal vascular filling (Figures 3 and 4). A portion of this area corresponded to an area of RPE atrophy. Other abnormalities included spots of blocked fluorescence corresponding to the pigment spots seen clinically. Superiorly, there was also a linear area of blocked fluorescence corresponding to the linear pigmentation seen on clinical examination. Fluorescein angiography of the left eye (Figure 5) showed numerous collateral vessels in the macula. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the right eye (Figure 6) shows no macular edema. OCT of the left eye (Figure 7) shows normal foveal contour.

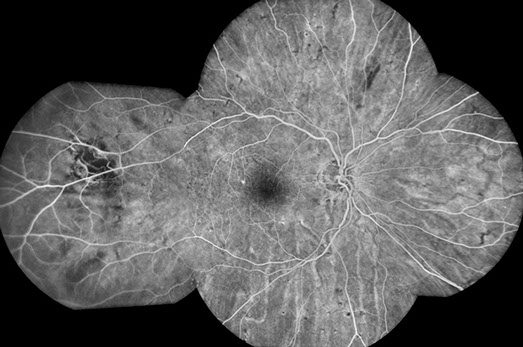

Figure 3: Early phase fluorescein angiogram of the right eye shows severely delayed choroidal filling.

Figure 4: Fluorescein angiogram montage of the right eye shows peripheral spots of hypofluoresence corresponding to the pigmented spots seen in color photos. There is blocking corresponding to the area of linear hyperpigmentation seen on color photos inferiorly, along with a focal area of choroidal nonperfusion temporally, corresponding to a large area of RPE atrophy.

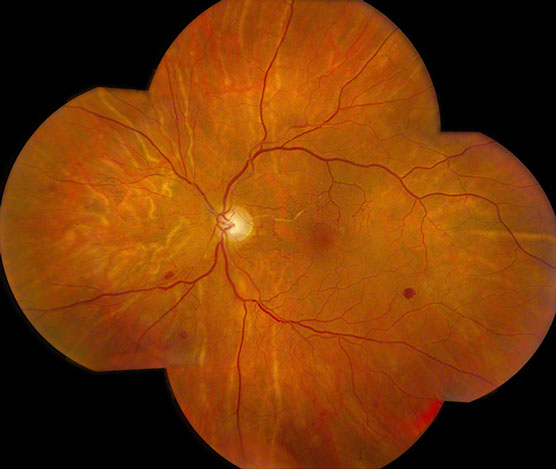

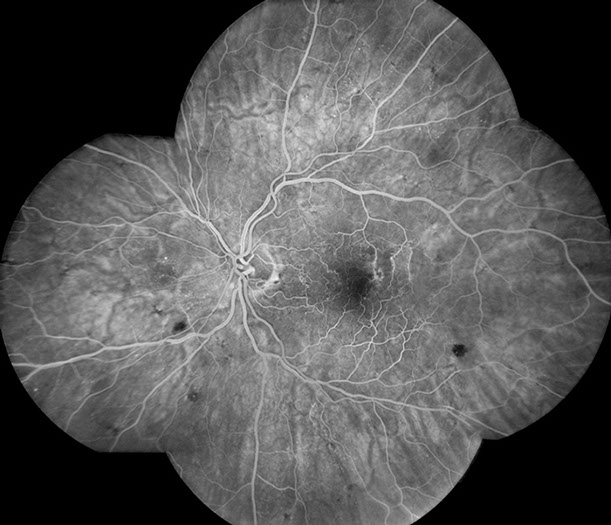

Figure 5: Fluorescein angiogram of the left eye shows multiple collateral vessels within the posterior pole. Note the hypofluorescent areas due to retinal hemorrhage.

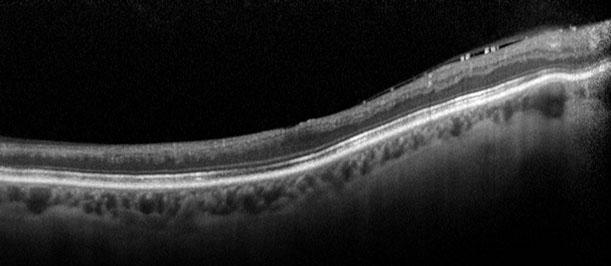

Figure 6: Spectral domain OCT scan through the right macula shows inner retinal thinning consistent with the disc pallor. No macular edema is present.

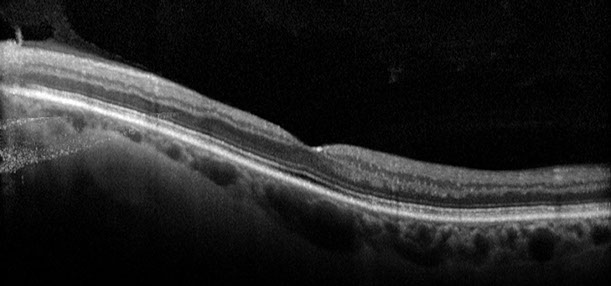

Figure 7: Spectral domain OCT scan through the left macula shows a normal foveal contour.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis

This 59-year-old man with progressive painless loss of vision for 2 months had significant retinal and choroidal vascular abnormalities on fundus examination and fluorescein angiography.

The differential diagnosis includes severe hypertensive retinopathy, giant cell arteritis, diabetic retinopathy, systemic lupus erythematosus, disseminated intravascular coagulation, retinal venous obstruction, hyperviscosity syndromes and radiation retinopathy.

Additional History

On further questioning, the patient described a syncopal episode that occurred several weeks prior to the onset of his vision loss. Evaluation at that time discovered a blood pressure of 250/190. During the hospitalization for treatment of his hypertensive crisis, he developed kidney failure necessitating dialysis. His blood pressure is currently controlled with four medications. His blood pressure at the time of our examination was 117/71.

Discussion

Our patient showed evidence of severe hypertensive retinopathy with cilioretinal artery obstruction in both eyes, choroidal ischemia and infarction in both eyes, and ischemic optic neuropathy in the right eye. These findings, although classic ocular sequelae of severe hypertension, are relatively uncommon to the extent manifested in our patient.

Anton Elschnig , a professor of ophthalmology in Prague from 1907 until 1933, described areas of impaired choroidal perfusion that now bear his name. Elschnig spots are small round depigmented areas with central pigment. They are believed to occur secondary to focal destruction of the choriocapillaris.1,2 Elshnig spots were noted in both eyes of our patient.

Siegrist first described the streaks that bear his name in 1899. They occur as a late effect of nonperfused choroidal vessels. Choroidal ischemia produces fibrinoid necrosis overlying a sclerosed choroidal vessel. Damage to the choriocapillaris leads to secondary retinal pigment epithelial atrophy followed by hypertrophy and hyperplasia 2 to 3 weeks later.3 Siegrist’s original report documented these lesions in a patient with malignant hypertension and one with giant cell arteritis.4 There have been only rare reports of Siegrist’s streaks in the literature.5 They are demonstrated in our patient’s right eye (Figure 1).

Hypertensive retinopathy manifests with retinal arteriolar changes, cotton-wool spots, retinal hemorrhages, and retinal edema. Chronic hypertension results in arteriolosclerosis that in turn produces the so-called copper-wire arteries. Precapillary arteriolar occlusion is the cause of cotton-wool spots. These fluffy white areas most commonly are seen within the posterior pole. Occlusion of the retinal capillaries and venules may lead to development of retinal vascular shunts and collaterals. Our patient had multiple collateral vessels in his left macula.6 If the retinal ischemia is sufficiently severe, neovascularization may occur.

Hypertensive choroidopathy results from the acute and chronic effects of choroidal ischemia and infarction. Acute choriocapillaris ischemia and occlusion can produce dysfunction of the RPE and serous retinal or retinal pigment epithelial detachment.7 The most common location of RPE abnormalities is the temporal portion of the macula and retina. Our patient showed a wedge-shaped area of RPE atrophy temporally in his right eye. Fluorescein angiography in our patient was even more revealing and demonstrated marked choroidal hypoperfusion secondary to severe hypertensive choroidopathy. This wedge-shape area of choroidal damage was described by Amalric.8 Infarction of a choroidal artery results in a triangular area of choroidal nonperfusion and overlying retinal pigment epithelial damage. This pattern of change is classically triangular, but can also lead to circular areas of atrophy. Our patient demonstrated the typical wedge-shaped area of nonperfusion and resulting retinal pigment epithelial atrophy temporally in his right eye.

Our patient had optic neuropathy with a pale right nerve. The primary source of blood supply to the optic nerve head is the posterior ciliary arteries. Severe hypertension results in vasoconstriction and occlusion of these vessels.6 In one study, hypertensive optic neuropathy was associated with a 90% mortality at one year,9 though this was not found in another study.10

There is evidence that the perfusion pressure of the cilioretinal artery is lower than that of the retinal circulation. On occasion cilioretinal artery occlusion occurs following a central retinal vein occlusion.11 In our patient a similar process may have resulted in closure of both cilioretinal arteries with swelling of the optic nerves during his acute hypertensive crisis potentially causing a secondary venous occlusion or stasis.

In summary, our patient exhibited multiple findings of hypertensive damage to the retina, choroid and optic nerve, including the much less commonly seen Elschnig spots and Siegrist’s streaks.

Take Home Points

- Severe hypertension can produce severe vascular damage to the retina, choroid and optic nerve.

- In the setting of acute hypertensive crisis, treatment should not lower the blood pressure too rapidly

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Libicky H. A personal sketch of Professor Anton Elschnig. Survey of Ophthalmology 26: 266-268, 1982..

- Morse PH. Elshnig’s spots and hypertensive choroidopathy. American Journal of Ophthalmology 66: 844-852, 1968.

- Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Ocular manifestations of giant cell arteritis. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 125:509-520, 1998.

- Coupal DJ, Patel AD. Siegrist streaks in giant cell arterititis. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 23:272-273, 2003..

- Puri P, Watson AP. Siegrist’s streaks: a rare manifestation of chroidopathy. Eye 15:233-34, 2001.

- Hayreh SS. Systemic arterial blood pressure and the eye. Eye 10:5-28, 1996.

- Ugarte U, et al. Hypertensive choroidopathy: recognizing clinically significant end-organ damage. Acta Ophthalmalogica 86: 2008.

- Amalric, P. Choroidal vascular ischemia. Eye 5:519-527, 1991.

- Kincaid-Smith P. Malignant hypertension: mechanisms and management. Pharmacologic Therapy 9:245-249, 1980.

- McGregor E, et al. Retinal changes in malignant hypertension. British Medical Journal. 1986. 233-234.

- Schatz H, et al. Cilioretinal artery occlusion in young adults with central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology 98:594-601. 1998