West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

January, 2015

Presented by Kevin Patel, MD

A 48 year-old woman presenting with decreased vision in the right eye.

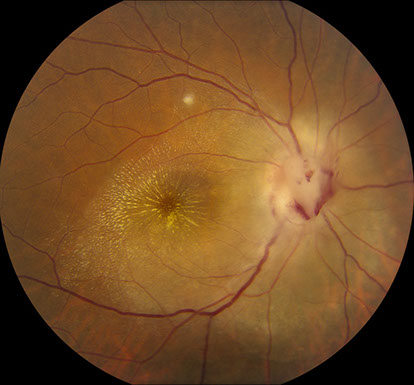

A

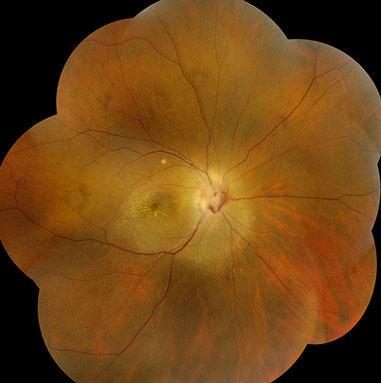

B

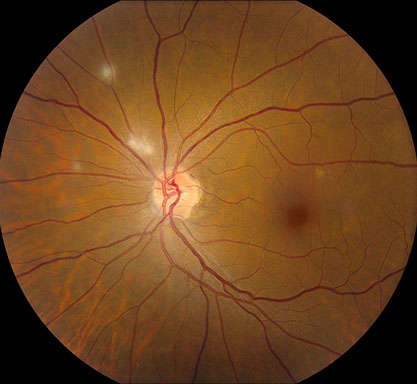

C

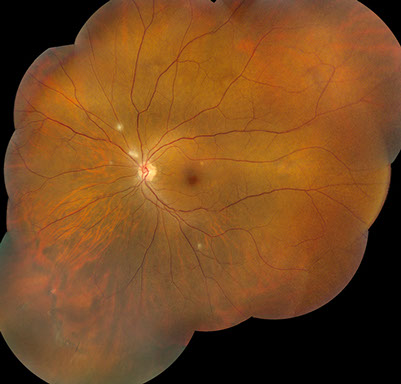

D

E

Figures 1A – E: Color fundus photographs of the right (A and B) and left eyes (C – E). The right fundus has florid optic disc edema with hemorrhage, peripapillary superficial retinal whitening, a macular star composed of exudates, and a small, focal area of retinitis in the superior macula (A and B). The left fundus has 4 small and distinct lesions of multifocal retinitis (C – E).

Case History:

A 48 year-old Guatemalan woman was referred for decreased vision in the right eye for 2-3 weeks duration with a sudden onset. The vision loss was profound, but the patient denied pain or any other ocular symptoms. There was also no significant past ocular history. The patient’s medical history was only significant for mild iron-deficiency anemia. The patient’s current medications were all recently started by the referring physician, and included azithromycin, prednisone, and omeprazole. A course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was also prescribed by the referring physician and finished by the patient shortly before presenting to us. The patient’s social history was notable for her having a cat as a pet and being born in Guatemala City but living in the United States for most of her life. There was no family history of any ocular conditions.

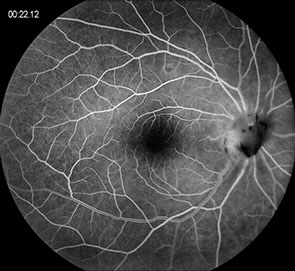

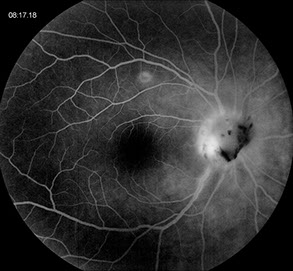

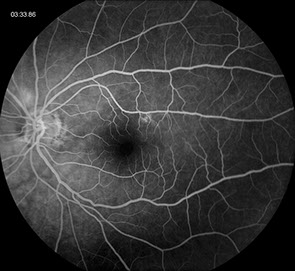

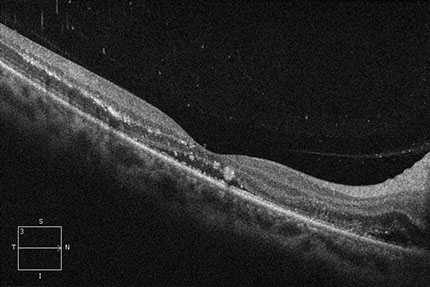

On examination, visual acuity was count fingers at 3 feet in the right eye and 20/40 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure and anterior segment examination were normal in both eyes. Posterior segment examination of the right eye was significant for 1+ cell in the anterior vitreous, florid optic disc edema with hemorrhage, peripapillary superficial retinal whitening, a macular star composed of exudates, a small, focal area of retinitis in the superior macula, and multiple pigmented chorioretinal scars inferiorly (Figures 1A and B). The left eye’s posterior segment examination was remarkable for 4 small and distinct lesions of multifocal retinitis and a pigmented chorioretinal scar inferonasally (Figures 1C – E). Fluorescein angiography (FA) of the right eye revealed staining of the retinitis and late hyperfluorescence of the optic disc consistent with disc swelling and leakage (Figures 2A and B). The FA of the left eye was only remarkable for staining of the areas of retinitis (Figure 2C). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the right eye demonstrated peripapillary and foveal subretinal fluid along with exudates diffusely throughout the outer plexiform layer and Henle’s fiber layer (Figure 3A). OCT of the left eye was unremarkable (Figure 3B). En face OCT of the right macula again displayed exudates within Henle’s fiber layer (Figure 4).

A

A

A

B

C

Figures 2A – C: Fluorescein angiogram of the right (A and B) and left (C) eyes. The right eye has early and late staining of the retinitis and late hyperfluorescence of the optic disc consistent with disc swelling and leakage (A and B). The left eye is only remarkable for minimal staining of the retinitis (C).

A

B

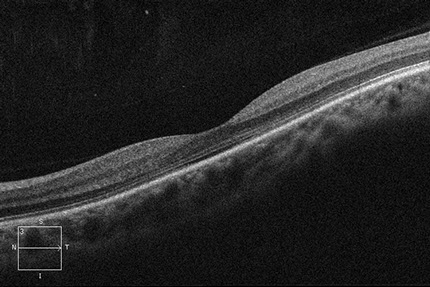

Figures 3A and B: Optical coherence tomography of the right (A) and left (B) maculas. The right macula demonstrates peripapillary and foveal subretinal fluid along with exudates diffusely throughout the outer plexiform layer and Henle’s fiber layer (A). The left macula is unremarkable (B).

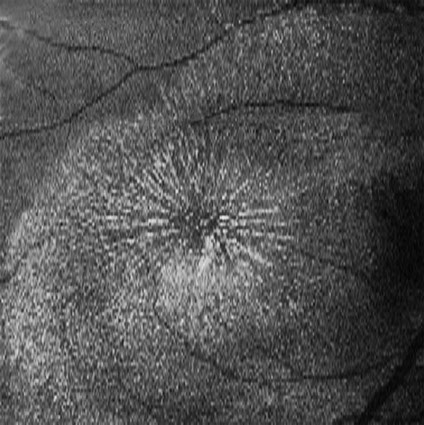

Figure 4: En face optical coherence tomography of the right macula displays exudates within Henle’s fiber layer.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis:

This case has both neuroretinitis (optic nerve edema with macular edema and macular star formation) and multifocal retinitis as presenting signs. The differential diagnosis of neuroretinitis can be split into infectious and non-infectious causes. Infectious causes include Bartonella henselae, Toxoplasma gondii, Treponema pallidum, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Toxocara sp, Rickettsia typhi, Leptospria sp, mumps virus, herpes viruses, and nematodes. Non-infectious causes include sarcoidosis and acute optic disc swelling in the setting of systemic vasculitis, such as Wegener’s disease, polyarteritis nodosa, and inflammatory bowel disease. Many cases of neuroretinitis can also be idiopathic. While this differential is very extensive, nearly two-thirds of cases result from Bartonella henselae infection. Such cases often have known exposure to cats and findings consisting of regional lymphadenopathy and multifocal retinitis or choroiditis. If there is bilateral neuroretinitis, causes of acute optic disc swelling must be considered, such as malignant hypertension, diabetic papillitis, pseudotumor cerebri, and systemic vasculitis.1

Additional Case History:

Given the concern for an infectious or autoimmune etiology, an extensive serological workup was performed. This included a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, HIV test, and testing for sarcoidosis (chest x-ray, angiotensin-converting enzyme level, lysozyme level), syphilis (rapid plasma reagin, Treponema pallidum particle treponema assay), tuberculosis (QuantiFERON-TB gold), toxoplasmosis (titers of IgM/IgG), and Bartonella henselae (titers of IgM/IgG). The patient’s presenting signs of neuroretinitis and multifocal retinitis and history of owning a cat made cat-scratch disease the most likely diagnosis. All testing was negative except for the IgM and IgG titers for Bartonella henselae, which confirmed the presumed diagnosis of cat scratch disease and ocular Bartonellosis. The patient was continued on oral azithromycin therapy and the prednisone was tapered.

The patient’s most recent follow-up was one month after initial presentation to our clinic. On that examination, visual acuity improved to 20/200 in the right eye and remained 20/40 in the left eye. Intraocular pressures and anterior segment examination of both eyes were again normal. Posterior segment examination of the right eye showed improving optic disc edema, a persistent macular star but no macular edema, and a smaller retinitis lesion. The left eye only demonstrated the previously-seen 4 retinitis lesions, all of which appeared smaller. The azithromycin was continued for 6 weeks, and the prednisone was tapered over the course of several weeks.

Discussion:

Infection with Bartonella henselae is commonly referred to as cat scratch disease. Transmission to humans is typically from exposure to cats, through cat scratches, bites, or contamination of open wounds with cat saliva. Cat scratch disease is typically a benign and self-limited condition. There is usually a localized papule or pustule at the primary inoculation site. A mild to moderately severe flu-like illness associated with regional lymphadenopathy occurs in most patients. Other systemic symptoms include headache, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and sore throat. Ocular infection can occur in 5 to 10% of patients.2

The most common ocular complication of cat scratch disease is Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome, which causes a unilateral granulomatous conjunctivitis. Patients present with redness, foreign body sensation, epiphora, serous discharge, and regional lymphadenopathy.2 Posterior segment manifestations of cat scratch disease include neuroretinitis, focal retinitis, focal choroiditis, multifocal retinitis or choroiditis, vasculitis, intermediate uveitis, vascular occlusions, and bacillary angiomatosis. Neuroretinitis occurs in only 1-2% of patients with cat scratch disease, however, nearly two-thirds of all patients with neuroretinitis are seropositive for Bartonella henselae.3 The neuroretinitis which occurs is typically unilateral and often accompanied by peripapillary subretinal fluid. Macular edema usually precedes the formation of a macular star by 2 to 4 weeks. A multifocal retinitis and/or choroiditis can occur in conjunction with neuroretinitis, and when present, this strongly supports the diagnosis of systemic Bartonella henselae infection. While most patients recover full vision, macular exudates can take months to resolve, and some patients may have mild disc pallor, subnormal contrast sensitivity, abnormal color vision, and abnormal evoked potentials.4

The classic clinical diagnosis of cat scratch disease requires at least 3 of the following 4 criteria to be met: (1) a history of traumatic cat exposure; (2) a positive skin test in response to cat scratch antigen; (3) characteristic lymph node lesions; and (4) negative laboratory investigations for unexplained lymphadenopathy. However, modern approaches now rely heavily on serologic testing, and to a lesser extent, culture or PCR-based analysis of tissue and/or fluid samples.5,6

There are still no clear treatment recommendations for cat scratch disease. Immunocompetent patients tend to have a self-limited infection, and antibiotics are likely only necessary for those cases with severe systemic or ocular complications. However, the therapeutic benefit of such treatment has never been demonstrated. In contrast, immunocompromised patients with Bartonella henselae infection tend to require systemic antibiotics, such as erythromycin or doxycycline. Doxycycline appears to be the preferred agent secondary to its greater intraocular and central nervous system penetration. While oral therapy is sufficient for most cases, more severe infections may require intravenous administration or combination therapy with rifampin. The duration of treatment is 2 to 4 weeks for immunocompetent patients and up to 4 months for immunocompromised patients.5,6

TAKE HOME POINTS:

- Neuroretinitis can be caused by an extensive number of infectious or non-infectious etiologies, or can also be idiopathic.

- Ocular infection with Bartonella henselae is the most common cause of neuroretinitis, and this condition often has the additional finding of multifocal retinitis.

- Treatment of ocular Bartonellosis in immunocompetent patients is controversial. While many cases of neuroretinitis presumed to be secondary to Bartonella infection are treated with systemic antibiotics, most cases will typically resolve with or without treatment in 2 to 4 months.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Cunningham ET Jr. What diseases should I consider in a patient with neuroretinitis? In Foster CS, Hinkle DM, Opremcak EM, eds. Curbside Consultation in Uveitis. Thorofare, NJ: Slack Book Incorporated;2012:103-6.

- Carithers HA. Cat-scratch disease. An overview based on a study of 1,200 patients. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139:1124-33.

- Ormerod LD, Skolnick KA, Menosky MM, et al. Retinal and choroidal manifestations of cat-scratch disease. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1024-31.

- Reed JB, Scales DK, Wong MT, et al. Bartonella henselae neuroretinitis in cat scratch disease. Diagnosis, management, and sequelae. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:459-66.

- Cunningham ET, Koehler JE. Ocular bartonellosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:340-9.

- Roe RH, Jumper JM, Fu AD, et al. Ocular bartonella infections. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2008;48:93-105.