West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

July, 2009

A 50-year-old highly myopic Chinese man presented with a one-day history of blurry vision and floaters in his right eye.

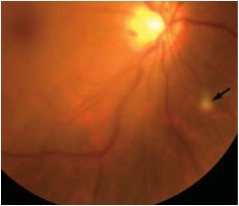

Figure 1: Color fundus photograph of the right eye. Note the focal area of retinitis inferonasal to the optic nerve(arrow)

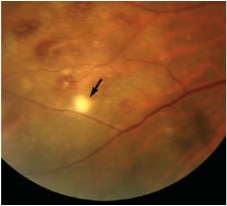

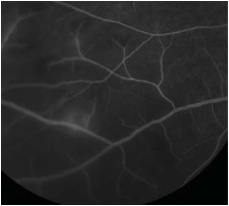

Figures 2A and B: Color fundus photograph of the right eye and corresponding mid-phase fluorescein angiogram. Note the areas of vasculitis and scattered intra-retinal hemorrhages.

Case History

A 50-year-old highly myopic Chinese man presented with a one-day history of blurry vision and floaters in his right eye. He denied pain, photophobia, and photopsia. His past medical and surgical histories were otherwise unremarkable. He was not taking any medications.

On examination, his best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/60 in the right eye and 20/40 in the left eye. His IOP was 15 mm Hg bilaterally. There was no afferent pupillary defect and his anterior segment examination was unremarkable. Dilated fundus posterior segment examination revealed 1+ vitritis bilaterally. In the right eye, there were small discrete areas of retinal whitening and scattered intra-retinal hemorrhages (Figure 1 and 2A). The left eye showed one small retinitis lesion area of retinal whitening superior to the fovea.

Fluorescein angiography revealed scattered areas of vasculitis (Fig. 2B). Laboratory work-up including complete blood count (CBC), serum Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR), Fluorescent Treponemal Antibody Absorption (FTA-Abs), Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE), Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Lyme titers, and Purified Protein Derivative (PPD) were all within normal limits. A chest x-ray was also normal.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis

The patient presented with acute bilateral non-granulomatous panuveitis with patchy retinal infiltrates and vasculitis. The differential diagnosis included syphilis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, Lyme disease, HIV retinopathy, herpetic retinitis, sarcoidosis, and Behçet’s disease.

Diagnosis

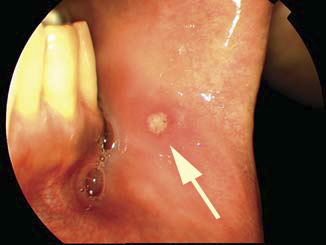

Normal laboratory investigations and radiologic testing excluded a diagnosis of syphilis, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, Lyme disease, HIV retinopathy, sarcoidoisis, or herpetic retinitis. Upon further questioning, the patient recalled recurrent fevers over the past several years with associated oral ulcers. Physical examination revealed an aphthous mouth ulcer (Fig.3)  and several acneiform skin nodules on the patient’s back. These associated systemic findings narrowed and confirmed the diagnosis to Behçet’s disease.

and several acneiform skin nodules on the patient’s back. These associated systemic findings narrowed and confirmed the diagnosis to Behçet’s disease.

Treatment

The patient was started on 60 milligrams mg/day of oral prednisone daily with a slow taper. He responded well to the oral corticosteroids with decreased vitreous inflammation and complete resolution of retinal hemorrhages, infiltrates, and vasculitis. His vision returned to 20/20 bilaterally.

Figure 3: Photograph of buccal mucosa. Note the aphthous ulcer (arrow).

Discussion

Behcet’s disease was first described in 1937 by the Turkish dermatologist Huluci Behcet as a triad of aphthous oral ulcers, genital lesions, and ocular inflammation It has since been recognized as a multisystem disease with variable clinical manifestations. Currently, the diagnosis is based on clinical characteristics of recurrent aphthous or herpetiform oral ulcer at least three times in one year. Additionally, patients must have two of the following: (1) recurrent genital ulcerations; (2) uveitis or retinal vasculitis; (3) erythema nodosum, pseudofolliculitis, papulopustular lesions, or acneiform nodules; (4) positive "pathergy test" in which a small sterile pustule develops at the site of venipuncture. (ref: International Study Group for Behcet’s Disease).

Behcet’s disease is most common in countries that extend from the Mediterranean, Middle East, to the Far East, along the ancient trading route known as the ‘Ssilk Rroad’. In these countries, the prevalence ranges between 8.5 per 100,000 in Japan to as high as 421 per 100,000 in Turkey. In contrast, this disease is rare in Northern Europe and United States, affecting 0.64 to 5.2 per 100,000 adults.

The etiology of Behcet’s disease is unknown, although immunologic factors are thought to play an important role. HLA-B51 is associated with Behcet’s in 70-80% of patients and this association is particularly pronounced in patients from the Middle and Far East. A recent meta-analysis of genetic association studies suggests a 6.3-fold increased risk of Behcet’s in HLA-B51 carriers. No infectious agent has been definitely linked to the pathogenesis of Behcet’s, however Streptococcus sanguis and various heat-shock proteins have been implicated. Currently, Behcet’s is believed to be a multi-factorial disease where dysregulated immune response is triggered by environmental agents, possibly microorganisms, in genetically susceptible individuals.

Clinical manifestations of Behcet’s result from obliterative vasculitis of small and large vessels of both the arterial and venous system. Mucocutaneous features are the most common presenting symptoms but ocular, vascular, and neurological involvement causes the most morbidity and mortality. Ocular involvement is seen in more than half of Behcet’s patients and usually follows the onset of oral and genital ulcers by a few years. Males and young patients are more frequently involved with earlier onset and more severe disease. In majority of cases, ocular disease is bilateral but may be asymmetrical. Patients typically presents with relapsing and remitting non-granulomatous panuveitis with variable degree of anterior uveitis. Although the classic teaching is that anterior hypopyon is the hallmark of Behcet’s disease, this finding is only observed in a small fraction of patients with ocular disease. Posterior segment inflammation can be severe with vitritis, papillitis, retinal hemorrhage and exudation, retinitis, retinal vasculitis, retinal venous or arterial occlusion, and choroiditis. Retinitis in Behcet’s is characterized by patchy white retinal infiltrates, as in our patient (Figure 1 and 2A). These areas of retinitis are easily distinguished from cotton-wool spots by their round or oval shape and by their occurrence in at or anterior to the mid-periphery, where the nerve fiber layer is too thin for cotton-wool spots to occur.

The natural course of ocular disease in Behcet’s is a progression repetitive attacks followed by remission. However, remission is slow in posterior uveitis and particularly absent in retinal vasculitis. The healing process is usually not completed before relapse. Sequela from successive attacks leads to severe vision loss.

The goal of treatment is to suppress acute inflammatory attack and prevent further relapse. Local and systemic corticosteroids are used for early control of acute inflammation. The duration of corticosteroids should be minimal and their dose should be tapered as soon as possible due to ocular and systemic side effects. Noncorticosteroid immunosuppressive agents are required to achieve long-term control in most patients. Azathioprine is the first line treatment, however, cyclosporin A, infliximab, etanercept,and the TNF inhibitors. Interferon-alpha have shown promising treatment benefit in patients with severe refractory diseases. Once the diagnosis of Behçet’s disease is established, it is important to involve a rheumatologist in the overall care and management of the patient.

Take Home Points

- Behcet’s is most common in the Mediterranean, Middle East, and Far East

- It is a multisystem disease characterized by the occurrence of obliterative vasculitis.

- Ocular involvement is seen in >50% of patients and presents as relapsing and remitting non-granulomatous panuveitis

- Vision loss most typically results from macular edema or macular ischemia.

- Patchy white retinal infiltrates as seen in our patient are highly suggestive for Behcet’s.

- Treatment requires corticosteroid for acute inflammation and immunosuppressive agents for long-term control

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G. Behcet's disease. N Engl J Med 1999;341(17):1284-91.

- Roe R Fisher C, Cunningham ET Jr. Morning Rounds: A case of Floaters and Fevers. EyeNnet 2006(May):53-4.

- Keino H, Okada AA. Behcet's disease: global epidemiology of an Old Silk Road disease. Br J Ophthalmol 2007;91(12):1573-4.

- Durrani K, Ahmed M, Foster CS. Adamantiades-Behcet disease: diagnosis and current concepts in management of ocular

- manifestations. Compr Ophthalmol Update 2007;8(4):225-33.

- Evereklioglu C. Current concepts in the etiology and treatment of Behcet disease. Surv Ophthalmol 2005;50(4):297-350.