West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

July, 2015

A 30 year-old woman with redness and pain in both eyes.

Presented by Kevin Patel, MD

A

B

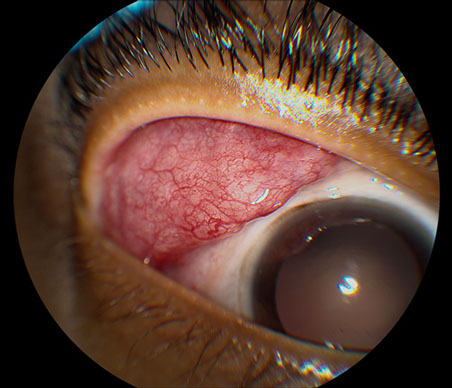

Figures 1A and B: Color external photographs of the right (A) and left (B) eyes. There is significant enlargement and inflammation of the right (A) and left (B) lacrimal glands.

Case History:

A 30 year-old African American woman presented with redness and pain of both eyes for several months duration. She also complained of new floaters in her left eye, but denied any other change or decrease in her vision. There was no significant past ocular history. The patient’s social and family histories were also noncontributory. She was presently using prednisolone acetate eye drops every hour in both eyes. She was otherwise using no other medications.

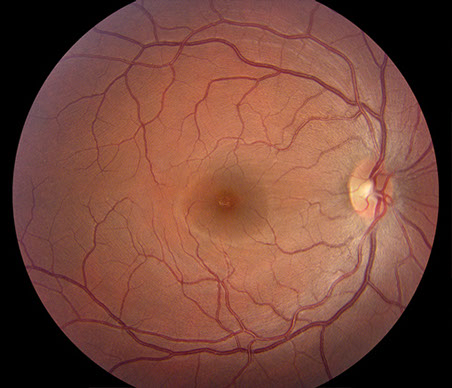

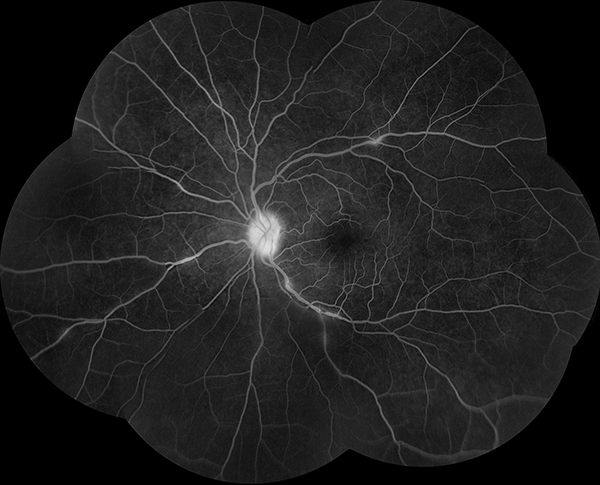

On examination, best-corrected visual acuity was 20/32 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure was normal in both eyes. On anterior segment examination, there was endothelial pigment on the cornea and 1+ cell in the anterior chamber of the right eye. The left eye only had trace flare in the anterior chamber. There was also significant lacrimal gland inflammation and enlargement bilaterally (Figures 1A and B). The posterior segment of the right eye was completely normal (Figure 2A). Posterior segment examination of the left eye was significant for mild vitritis, optic disc swelling, and segmental retinal phlebitis (Figures 2B and C). Fluorescein angiography (FA) of the right eye was unremarkable (Figure 3A), while the left eye demonstrated hyperfluorescence of the optic disc and of the areas of segmental phlebitis (Figure 3B).

A

B

C

Figures 2A-C: Color fundus photographs of the right (A) and left (B and C) eyes. The posterior segment of the right eye is unremarkable (A). The left fundus is significant for mild vitritis optic nerve swelling, and several areas of retinal phlebitis (B and C).

A

Figures 3A and B: Fluorescein angiogram of the right (A) and left (B) eyes. The right eye is normal (A) while the left eye demonstrates hyperfluorescence of the optic nerve and areas of phlebitis (B).

What is your Diagnosis?

B

Differential Diagnosis

This patient had both panuveitis and bilateral lacrimal enlargement. The differential diagnosis of is broad and includes: sarcoidosis, lymphoma, or infection – including tuberculosis, syphilis, herpes virus infection or orbital cellulitis.

Additional Case History

The patient was started on high-dose oral corticosteroids, which resulted in a rapid decrease of her ocular inflammation and improvement in vision to 20/20 in both eyes. There was no cell or flare in her anterior chambers bilaterally and the optic disc edema and phlebitis improved in the left eye. The lacrimal gland inflammation also had resolved. While tapering her oral corticosteroids, the patient had a recurrence of lacrimal gland inflammation and the oral corticosteroids were restarted. Sub-Tenon’s corticosteroid injections were performed bilaterally, which allowed for control of the patient’s ocular inflammation while tapering off of oral corticosteroids.

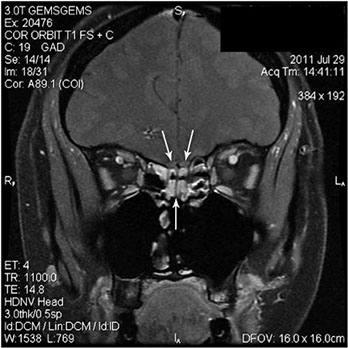

Approximately 5 months after her initial presentation, the patient developed a sudden onset of anosmia. She had no ocular inflammation and visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/16 in the left eye. MRI with contrast of the brain and orbits revealed soft tissue enhancement in the posterior ethmoid sinuses and ethmoidal recesses of the naris, which are in close proximity to the olfactory bulbs (Figure 4). There was no intracranial extension.

While there are many causes of anosmia, only a few conditions can cause panuveitis along with the loss of sense of smell, including sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, granulomatosis with polyangitis, and lymphoma. Given that our patient also had lacrimal gland inflammation and rapid resolution of her ocular inflammation with oral and periocular corticosteroids, the most likely diagnosis was sarcoidosis causing panuveitis and rhinosinusitis.

History withheld for purpose of this discussion was the fact that our patient had a well documented history of systemic sarcoidosis, which included elevated systemic levels of lysozyme and angiotensin converting enzyme and evidence of bilateral hilar adenopathy on chest imaging. Previsous biopsy of her conjunctiva demonstrated non-caseating granulomas, consistent with a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

The patient was started on oral corticosteroids, which resulted in improvement of her anosmia over several months. The corticosteroids were slowly tapered while she was transitioned to systemic methotrexate. There was no ocular inflammation noted during nearly 2 years of follow-up while the patient was treated with methotrexate and low-dose oral corticosteroids. Her visual acuity remained stable at 20/20 bilaterally.

Figure 4: Coronal section of MRI with contrast of the brain and orbits. There is soft tissue enhancement in the posterior ethmoid sinuses and ethmoidal recesses of the naris (single arrow), which are in close proximity to the olfactory bulbs (white arrows).

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is a systemic inflammatory disease of unknown cause associated with the formation of noncaseating granulomas. Ocular involvement is relatively common and can occur in up to 40% of patients. Ocular sarcoidosis can manifest itself in numerous ways, including granulomatous uveitis, orbital or eyelid granulomas, lacrimal gland infiltration, choroidal granulomas, or optic nerve infiltration. Sarcoid uveitis may be anterior, intermediate, posterior, or present as a panuveitis. Anterior uveitis is the most common. An international group of uveitis specialists (International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis in 2009) and identified 7 signs in the diagnosis of intraocular sarcoidosis. These include: (1) mutton-fat keratic precipitates (KPs)/small granulomatous KPs and/or iris nodules (Koeppe/Busacca), (2) trabecular meshwork (TM) nodules and/or tent-shaped peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS), (3) vitreous opacities displaying snowballs/strings of pearls, (4) multiple chorioretinal peripheral lesions (active and/or atrophic), (5) nodular and/or segmental peri-phlebitis (+/- candlewax drippings) and/or retinal macroaneurysm in an inflamed eye, 6) optic disc nodule(s)/granuloma(s) and/or solitary choroidal nodule, and (7) bilaterality.1

Fundus lesions in sarcoidosis more frequently involve the retina than the choroid. In addition to phlebitis, which can be extensive and form candlewax dripping exudates, other characteristic findings include string of pearls vitreous opacities, focal superifical and deep white retinal nodules, papilledema, nodular papillitis, optic neuritis, occasional large white masses on the inner retina or optic nerve head, focal granulomas under the RPE and within the choroid, and choroidal inflammatory lesions of varying size.2

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is suggested by elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme and/or lysozyme levels and chest imaging (x-ray or CT scan) revealing bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Patients should also have a negative tuberculosis test. Definitive diagnosis requires a tissue biopsy demonstrating noncaseating granulomas. Treatment of ocular sarcoidosis consists of corticosteroids initially (topical, oral, or periocular) with transition to immunosuppressive agents as necessary.2

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease and most often involves the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, and eyes. However, sarcoidosis can also affect nasal tissue and sinuses, leading to sarcoid rhinosinusitis. In a study evaluating 36 patients with sarcoid rhinosinusitis, there were a number of characteristic signs and symptoms identified. These included nasal obstruction (86%), nasal crusting (47%), anosmia (44%), epistaxis (28%), and nasal polyposis (25%). The rhinosinusits was treated in the majority of patients with oral corticosteroids initially and later with steroid-sparing medications, with methotrexate most commonly used.3

While anosmia in patients with sarcoidosis can be secondary to sarcoid rhinosinusitis, the possibility of neurosarcoidosis must also be considered. Neurosarcoidosis is a rare entity, seen in only 5% of cases of sarcoidosis. Symptoms from neurosarcoidosis are secondary to meningeal, cranial nerve, hypothalamus, pituitary, and spinal cord involvement.4 One of the few case reports of neurosarcoidosis discussed a 51-year-old Caucasian male who presented with a 6-year history of anosmia and 6 weeks of visual changes. On exam, he had a left afferent pupillary defect and dense left nasal hemianopsia. MRI with contrast showed an enhancing bilateral subfrontal mass that extended into the left optic chiasm and left basal ganglia. Subsequent biopsy of the right ethmoid sinus roof demonstrated noncaseating granulomas consistent with sarcoidosis. Prompt treatment with intravenous corticosteroids resulted in improvement of his visual field deficit and visual acuity.5

Take Home Points

- Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease that often has ocular involvement. A common manifestation of ocular sarcoidosis is panuveitis.

- Sarcoidosis can also cause rhinosinusitis, which often leads to the characteristic symptom of anosmia.

- Patients with sarcoidosis who develop anosmia must also be evaluated for cranial involvement, as neurosarcoidosis may cause anosmia as a presenting symptom.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Herbort CP, Rao NA, Mochizuki M, et al. International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: results of the first International Workshop On Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS). Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:160-9.

- Agarwal A. Gass’ Atlas of Macula Diseases, 5th ed. Elsevier; 2012. Pg. 1022-27.

- Reed J, deShazo RD, Houle TT, et al. Clinical features of sarcoid rhinosinusitis. Am J Med. 2010;123:856-62.

- Stern BJ, Krumholz H, Johns C, et al. Sarcoidosis and its neurological manifestations. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:909-17.

- Kieff DA, Boey H, Schaefer PW, et al. Isolated neurosarcoidosis presenting as anosmia and visual changes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:S183-6.