West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

June, 2011

A 57-year-old Nigerian man with mild, gradual decline in the vision in his right eye.

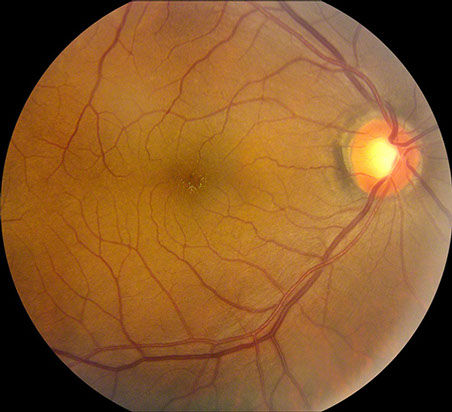

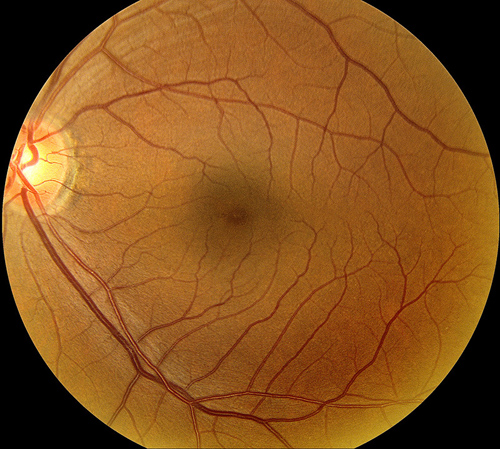

Figure 1: The color fundus photograph of the right eye revealed multiple intraretinal yellow-green crystals surrounding the center of the fovea. The color fundus photograph of the left eye was normal.

Case History

A 57-year-old Nigerian man noted a slight and gradual decrease in the vision in his right eye over the past several years. He was struck in the right eye by a bungee cord 30 years ago. He denied any previous ocular surgery. His past medical history was significant for hypertension and recently diagnosed diabetes mellitus, which was under good control. He underwent surgery for prostate cancer one year prior to presentation. The type of anesthesia used was not known. His medications included Metformin and aspirin. He denied any family history of eye problems. He admitted to occasional use of marijuana as well as a remote history of kola nut consumption.

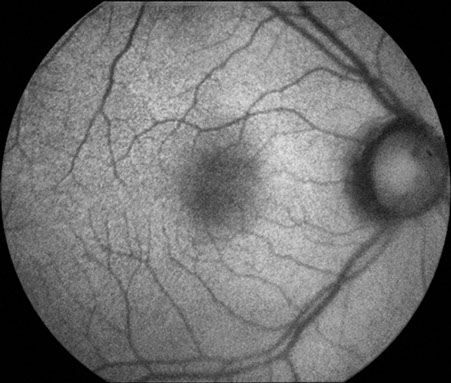

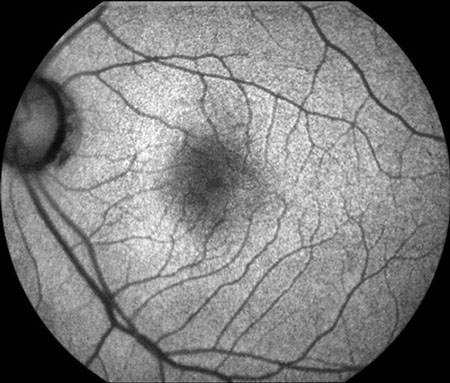

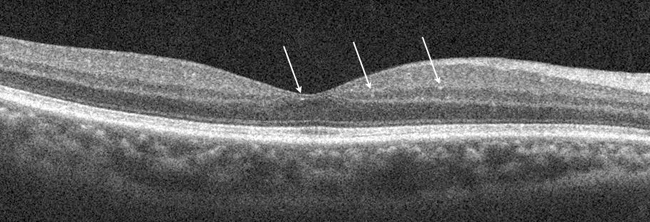

On examination, the best-corrected visual acuity was 20/25-1 in the right eye and 20/16-2 in the left eye. The intraocular pressure was normal in each eye and the blood pressure was 143/108. The anterior segment examination revealed clear corneas and a cortical sector cataract in the right eye. The dilated fundus examination revealed clear media and a moderately increased cup-to-disc ratio in each eye. There were yellow-green intraretinal refractile deposits near the center of the fovea of the right eye (Figure 1). The retinal vessels, macula, and periphery of the left eye were normal. Macular edema was not present in either eye. Fundus autofluorescence was normal bilaterally (Figure 2). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed small intraretinal hyper-reflective lesions in the macula of the right eye (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Fundus autofluorescence imaging of both eyes was normal

Figure 3: Spectral domain optical coherence tomography revealed small intraretinal hyper-reflective lesions in the macula of the right eye. In this slice, the arrow points to one such crystal. The findings were subtle.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of crystals within the retina is broad and includes toxic, metabolic, degenerative, genetic, vascular, and idiopathic causes (Table).1,2 Most toxic etiologies can be ruled out as the distribution of crystals with these entities differs from that of our patient. In addition, our patient denied consumption of ethylene glycol, tanning agents, or any medications, such as tamoxifen, nitrofurantoin, and ritonavir, which have been associated with crystalline retinopathy. Canthaxanthine is a tanning agent that typically causes crystals that are distributed in a ring surrounding the foveal avascular zone, in a fashion distinct from that seen in our patient.1 Tamoxifen, a medication used in women with breast cancer, typically causes crystal deposition in the temporal macula. Ritonavir, a protease inhibitor used in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), has been noted to cause macular crystals associated with retinal pigment epitheliopathy and parafoveal telangiectasia,3 which were not present in our patient. Although he did undergo prior surgery, our patient’s presentation was not consistent with methoxyflurane toxicity, in which crystals are deposited within the retinal pigment epithelium and along retinal arterioles.

Metabolic causes of crystalline retinopathy, including secondary hyperoxaluria, can be ruled out based on the absence of systemic findings, including sarcoidosis, liver cirrhosis, small bowel resection, and renal failure, which may predispose to oxalate hyperabsorption.2

Genetic etiologies of crystalline retinopathy can also be excluded based on our patient’s clinical presentation. The absence of RPE abnormalities and nyctalopia make Bietti’s crystalline dystrophy unlikely. Sjogren Larsson syndrome, primary hyperoxaluria, and cystinosis are often associated with renal disease, which was not present in our patient. Hyperoxaluria also causes a characteristic black subretinal plaque, which also was not seen in our patient.4 Our patient’s fundus did not exhibit the typical pattern of chorioretinal atrophy with scalloped borders that is associated with gyrate atrophy.

Vascular causes of crystals within the retina are also improbable based on our patient’s clinical presentation. Juxtafoveal telangiectasia is unlikely given the absence of right angle retinal venules, retinal telangiectasis, and macular edema.5 Talc retinopathy is improbable as well since our patient denied intravenous drug use and since the crystals were not white nor located within retinal arterioles.2

Idiopathic causes of crystals within the retina include white dot fovea6 and chronic retinal detachment.1 White dot fovea was originally described in 30 Japanese patients with refractile lesions that were thought to simulate macular holes and were bilateral in greater than 90% of cases.6 The clinical characteristics of patients with white dot fovea are inconsistent with those seen in our patient. In addition, careful clinical examination of our patient did not reveal a retinal detachment.

Differential Diagnosis of Crystalline Retinopathy

Genetic Disease

Bietti's Crystalline Dystrophy

Gyrate Atrophy

Cystinosis

Sjogren-Larrson Syndrome

Primary Hereditary Hyperoxaluria

Vascular Disease

Idiopathic Justafoveal Telangiectasis

Talc Retinopathy

Idiopathic

Chronic Retinal Detachment

White Dot Fovea

Toxic Exposure

Canthaxanthine

Tamoxifen

Nitrofurantoin

Secondary Hyperoxaluria

Methoxyflurane

Ethylene Glycol (antifreeze)

Other

Metabolic Disorders

Secondary Hyperoxaluria

Excessive rhubarb ingestion

Hyperabsorption of oxalate

Sarcoidosis

Liver Cirrhosis

Small Bowel Resection

Renal Failure

Discussion

West African crystalline maculopathy (WACM) is an entity involving multiple birefringent yellow-green refractile crystals within the macula of individuals from Western Africa.7-9 In the first report by Sarraf and colleagues, all of the patients were from the Igbo tribe of Nigeria. Subsequent reports have described other patients from other West African tribes and countries.7-9 Although WACM is often associated with visually significant retinal vascular diseases, patients with WACM are often asymptomatic as the crystals themselves do not seem to be of visual consequence.9 Most cases of WACM are bilateral, but a patient with unilateral crystals has been described.7 Unlike other causes of crystalline retinopathy, such as Bietti’s crystalline dystrophy, hyperoxaluria, and talc retinopathy, WACM seems to cause refractile deposits within the vascular arcades and not in the retinal periphery.8

Ocular imaging may be of some utility in WACM. Rajak and associates identified with OCT crystals in the layer of Henle in the fovea.7 The authors postulated that either the crystals pass through a damaged blood retinal barrier or that ischemia reduces the rate of flow in the axons, leading to precipitation of crystals in the layer of Henle.7 Fluorescein angiography (FA) is typically normal in patients with WACM.9

The pathophysiology of WACM is unclear but genetic, degenerative, and toxic mechanisms have been proposed. Because many cases have occurred within the same geographic region and tribe, a genetic cause has been suggested. Close blood relatives of patients with WACM, however, have not been found to have crystalline maculopathy.9 The authors of the original paper describing WACM also suggested a degenerative mechanism in WACM because all patients were older than 50 years of age.9 A subsequent series, however, included two patients who were younger than 50 years old, suggesting that a degenerative etiology alone is unlikely.7

A toxic cause, involving either kola nuts or specific foods that are unique to countries in western Africa, seems to be most likely in the pathophysiology of WACM. The kola nut, which contains a stimulant with addictive potential, as well as xanthines that may be deposited in various tissues in the body, is consumed ritualistically in many West African countries.9 In the original description of WACM, many patients admitted to consumption of kola nuts, which suggested a potential cause of the crystals. It has been subsequently noted, however, that several patients with WACM have denied any history of kola nut consumption. An alternative theory implicates certain foods, including pumpkin greens, African palm oil, afanga greens, as well as cassava greens and roots, which are unique to west African countries.8

Vasculopathy, related to either diabetes mellitus or other retinal vascular diseases, likely represents a precipitating factor in WACM that must be present in order for the manifestations of the crystals. All patients with WACM have been shown to have either diabetes or another significant retinal vascular disease, such as sickle cell retinopathy, branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) or familial exudative vitreoretinopathy.7, 8 Moreover, the crystals in WACM are often located within the area of blood retinal barrier breakdown, such as in the vascular distribution of a BRVO.7

West African Crystalline Retinopathy is a peculiar and fascinating entity. Despite its appearance, visual acuity is typically excellent and the natural history appears to be benign. Treatment for underlying systemic entities such as diabetes is warranted, but no specific intervention is necessary for the crystals.

Take Home Points

- The differential diagnosis of crystalline retinopathy is broad and includes toxic, metabolic, degenerative, genetic, vascular, and idiopathic causes (Table)

- West African crystalline maculopathy (WACM) involves the deposition of yellow-green refractile deposits within the retina of patients from countries in Western Africa

- The etiology of WACM is not clear but toxic causes, including the kola nut and certain foods that are indigenous to West African countries, have been suggested

- Although all patients with WACM have either coexistent diabetes or other retinal vascular diseases, many patients with WACM are asymptomatic and the crystals themselves do not seem to be of visual consequence

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Ahmed I, McDonald HR, Schatz H, et al. Crystalline retinopathy associated with chronic retinal detachment. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116(11):1449-53.

- McDonald HR. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Retina 2001;21(6):652-6.

- Roe RH, Jumper JM, Gualino V, et al. Retinal pigment epitheliopathy, macular telangiectasis, and intraretinal crystal deposits in HIV-positive patients receiving ritonavir. Retina;31(3):559-65.

- Meredith TA, Wright JD, Gammon JA, et al. Ocular involvement in primary hyperoxaluria. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102(4):584-7.

- .Moisseiev J, Lewis H, Bartov E, et al. Superficial retinal refractile deposits in juxtafoveal telangiectasis. Am J Ophthalmol 1990;109(5):604-5.

- Yokotsuka K, Kishi S, Shimizu K. White dot fovea. Am J Ophthalmol 1997;123(1):76-83.

- Rajak SN, Mohamed MD, Pelosini L. Further insight into West African crystalline maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127(7):863-8.

- Browning DJ. West African crystalline maculopathy. Ophthalmology 2004;111(5):921-5.

- Sarraf D, Ceron O, Rasheed K, et al. West African crystalline maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121(3):338-42.