West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

March, 2010

Presented by Evelyn Fu, MD

A 48-year-old man presented with a one-month history of a nasal shadow.

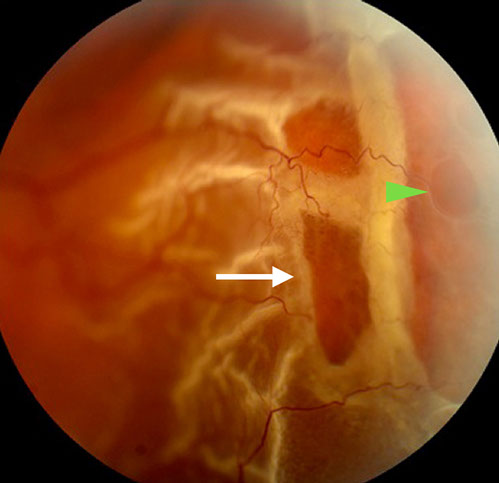

Figures 1: A bullous retinal detachment extending from two o’clock to five o’clock is present in the temporal periphery of the left eye. There are several large outer retinal holes with rolled edges (arrow), and an inner retinal hole (arrowhead).

Case History

A 48-year-old man presented with nasal visual field loss in the left eye for one month. His past ocular and medical history were non-contributory. He was not a high myope and had no previously documented lattice degeneration. He denied any history of ocular trauma.

On examination, best-corrected visual acuity was 20/13 in the right eye and 20/16 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure and anterior segment examination were normal in each eye. The right fundus was normal. In the temporal periphery of the left eye, there was a bullous retinal detachment extending from two o’clock to five o’clock (Figure 1). The retinal detachment appeared to be caused by two large breaks with rolled edges. The retina was opacified in the distribution of the detachment, with a corrugated appearance. However, closer examination revealed retinal vessels within the translucent inner retina coursing over these breaks. (Figure 1). A round, smaller break within the inner retina was visible.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis

Retinal detachments are classified in four major categories; tractional, exudative, rhegmatogenous, and combined traction-rhegmatogenous. Traction-induced retinal detachments are seen in the setting of fibrovascular proliferative contraction with secondary retinal detachment. Exudative detachments are associated with retinal vascular, retinal pigment epithelial, or optic disc leakage resulting in dome-shaped detachments and the classically described “shifting” subretinal fluid.

The diagnosis of rhegmatogenous detachment is characterized by two features. First, the finding of a full thickness retinal break in association with a retinal detachment is pathognomonic. Second is the corrugated appearance of the retina when detached. Even in the absence of a visible retinal break, this appearance as seen in our patient, is highly suspicious for rhegmatogenous detachment.

Traumatic rhegmatogenous detachment results from sudden compression-expansion injury of the globe with traction suddenly induced at the vitreous base, resulting in retinal dialysis or giant retinal tear. A history of ocular blunt trauma should alert the clinician of the potential for retinal dialysis and giant retinal tear prompting peripheral examination with scleral depression.

Non-traumatic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment most commonly develops when a retinal break forms from vitreoretinal traction. These retinal detachments are seen in the setting of acute posterior vitreous detachment and lattice degeneration. However, degenerative conditions such as atrophic holes, lattice degeneration with atrophic holes, retinoschisis, and retinal tuft may also result in non-traumatic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.

The finding of a corrugated retinal appearance with outer retinal holes with an overlying intact inner retina is likely the result of rhegmatogenous detachment secondary to inner and outer wall retinal defects. Thus, our patient developed a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment as a result of inner and outer retinal hole formation in a retinoschisis cavity.

Discussion

Retinoschisis is notable for juvenile X-linked recessive retinoschisis and degenerative retinoschisis forms. Degenerative retinoschisis was first reported by Bartels in 1933.1 It develops as intraretinal microcysts located in an area of peripheral cystoid degeneration near the ora serrata coalesces. This process results in the splitting of the retina at the outer plexiform layer and causes irreversible and complete loss of visual function in the affected area. Degenerative retinoschisis is idiopathic, and occurs equally in men and women with an incidence of 3.7% in patients 10 years or older and 7% in patients 40 years of age or older. Eighty percent of the patients have bilateral involvement.2

Degenerative retinoschisis is most commonly found in the inferotemporal quadrant.3 Ophthalmoscopy reveals a smooth stationary elevation without folds and undulation upon eye movement. The inner layer is often transparent and may be difficult to visualize. Whitish deposits, sometimes referred to as "snowflakes", and non-perfused, sclerotic retinal vessels can be found on the inner surface. Because the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is not disrupted by retinoschisis, hyperplasia does not occur and a demarcation line does not form. If a pigmented demarcation line is present in the setting of retinoschisis, concomitant rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is present. Scleral depression is essential in distinguishing retinoschisis from retinal detachment. In contrast to retinal detachment, scleral indentation fails to collapse the cavity in retinoschisis.

The natural history of retinoschisis in the absence of inner and outer wall breaks is typically benign, with uncommon , posterior extension. Progression, when present, is slow, frequently stops spontaneously, and rarely reaches the macula. In the largest published series, Byer described the natural history of retinoschisis in 218 eyes studied for an average of 9.1 years4. No cases of symptomatic progression occurred, but 14 cases of localized nonprogressive asymptomatic “schisis detachment” occurred. Buch and colleagues reported a prevalence rate of 3.9% in those 60-80 years of age in Copenhagen, with a possible risk of increased retinoschisis progression in those receiving cataract surgery.3

The development of retinal holes in the inner and outer layers heralds a significant complication. Inner layer holes are usually small and difficult to visualize. Outer layer holes are more common and are often large with prominent rolled posterior borders. The presence of inner retinal holes alone does not increase the risk of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment as the fluid in the vitreous has no access to the subretinal space. Retinal detachment may occur when retinal holes develop in the outer layer alone or in both the inner and outer layers. Patients with only outer retinal holes have localized and relatively stable detachment whereas those with holes in both layers develop symptomatic rapidly progressive detachment. Treatment for retinoschisis should be limited to patients with symptomatic, progressive retinal detachments.4 Prophylactic treatment is not recommended for asymptomatic patients with localized nonprogressive retinal detachment or with posterior extension not threatening the macula. These patients should, instead, be followed periodically and instructed to return immediately in the unlikely event that they become symptomatic.

Treatment of rhegmatogenous retinal detachments arising from degenerative retinoschisis typically involves surgical repair. Scleral buckling, pars plana vitrectomy, or combined scleral buckle with vitrectomy have been described. Restoration of the rhegmatogenous component may improve visual field deficits, however patients are counseled that an absolute visual field defect corresponding to the retinoschisis will persist.

Take Home Points

- Degenerative retinoschisis results from an idiopathic process in which the intraretinal microcysts coalesce and cause splitting of the retina at the outer plexiform layer.

- The majority of retinoschisis remains stable with rare cases of posterior extension, retinal hole formation, and retinal detachment.

- Treatment for retinoschisis should be limited to patients with symptomatic, progressive retinal detachments.

- Asymptomatic patients with posterior extension not threatening the macula or with localized nonprogressive retinal detachment should be monitored closely

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- M. Bartels, Uber die Entsdehung von Netzhautablosungen, Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 91 (1933), pp. 437–450.

- N.E. Byer, Clinical study of senile retinoschisis, Arch Ophthalmol 79 (1968), p. 36.

- Buch H, Vinding T, Nielsen NV. Prevalence and long-term natural course of retinoschisis among elderly individuals: the Copenhagen City Eye Study. Ophthalmology. Apr 2007;114(4):751-5.

- N.E. Byer, The long-term natural history of senile retinoschisis with implications for management, Ophthalmology 93 (1986), p. 1127.