West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

March, 2013

A 56 year-old man with several months of blurred vision.

Presented by Paul Stewart, MD

A

B

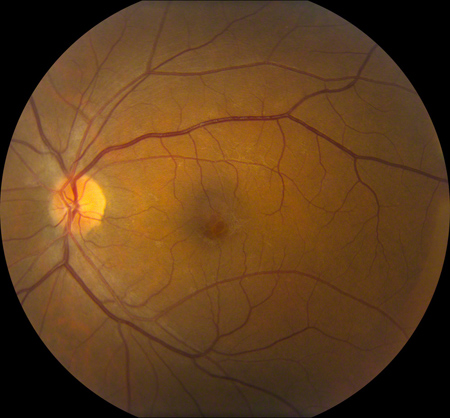

Figures 1A and B: Color photos of the right and left eye. The optic nerves in each eye are normal. There is a sheen in each macula. The left macula has a cystic appearance. A posterior vitreous detachment is present in the right eye with a visible floater along the inferior arcade.

Case History

A 56 year-old man was referred for the evaluation of possible central serous retinopathy of the left eye. He had noticed decreased vision in both eyes for several months. There was no history of ocular surgery or trauma. The patient’s vision was 20/32 in both eyes. Intraocular pressures were 15mm Hg in both eyes. Anterior segment examination was normal in both eyes.

The dilated fundus examination of the right eye revealed clear ocular media without any vitreous cell. A posterior vitreous detachment was present with a prominent vitreous floater. The optic nerve was healthy. Within the macula there was a mild sheen to the surface of the retina with loss of the foveal light reflex (Figure 1A). The dilated fundus examination of the left eye showed a healthy optic nerve. The left macula showed a cystic appearance (Figure 1B).

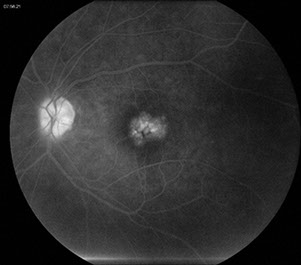

On fluorescein angiography both eyes showed early and late leakage in the macula (Figures 2A and B) that was most prominent in the left eye. No other abnormalities were present.

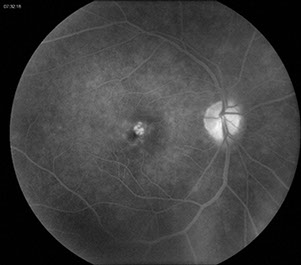

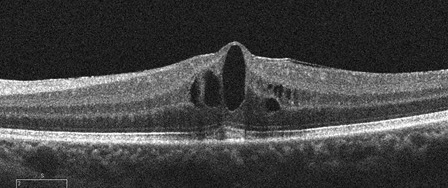

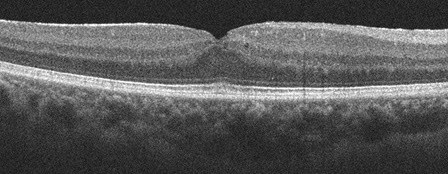

Optical coherence tomography showed intraretinal cystic edema in both eyes (Figures 3A and B).

A

B

C

Figures 2A-C: Fluorescein angiography of the left and right macula showing perifoveal capillary dilation and late leakage in each macula.

A

B

Figures 3A and B: SD-OCT horizontal scans through each macula showing intraretinal cystic changes bilaterally.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis

Cystoid macular edema (CME) can be found after a variety of ocular procedures including cataract surgery, penetrating keratoplasty, scleral buckling, laser iridotomy, cryotheraphy and panretinal photocoagulation. Bilateral cystoid macular edema can be associated with an inherited condition such as retinitis pigmentosa or autosomal dominant cystoid macular edema. CME can also be associated with ocular tumors such as choroidal melanoma, choroidal hemangioma and vasoproliferative tumors. CME can be associated with traction either from epiretinal membranes or vitreomacular traction syndrome. Many inflammatory conditions can cause CME including pars planitis, idiopathic vitritis, Behcet’s, birdshot, sarcoidosis, scleritis, toxoplasmosis and Eales’ disease. Vascular conditions can also cause CME including retinal vascular occlusions, diabetic macular edema, macular telangiectasia, polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, Coat’s disease, acute hypertensive retinopathy, radiation retinopathy, retinal arterial macroaneurysms and ocular ischemic syndrome. A variety of medications have also been shown to cause CME including niacin, topical epinephrine, taxane-based chemotherapy, thiazolidinediones, topical prostaglandin analogues, and fingolimod.

Clinical Course

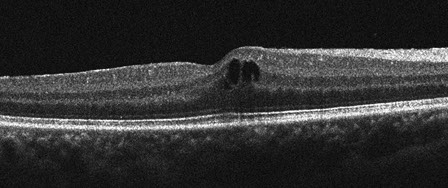

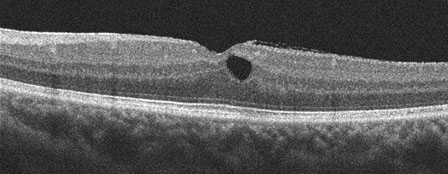

On further questioning the patient was found to have hypertension well-controlled with amlodipine. He also has recently been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Three months prior to presentation and just prior to the onset of his symptoms he was started on Gilenya (fingolimod) 0.5mg daily. The patient was diagnosed with cystoid macular edema related to his use of fingolimod. His condition was discussed with his neurologist who strongly desired to keep him on fingolimod to control his multiple sclerosis. The patient was started on Nevanac four times daily and he responded with decreased CME (Figs 4A and B) and his vision has returned to 20/20. At no time during his follow-up has he had any vitreous cell or other signs of inflammation.

A

B

Figures 4A and B: SD-OCT horizontal scans through each macula. The intraretinal cystic changes have decreased substantially with Nevanac treatment.

Discussion

Fingolimod is the first, and currently only, oral agent approved for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. It is a sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator. It renders T and B cells insensitive to signaling necessary for egress from secondary lymphoid tissues.1 This mechanism is thought to reduce the recirculation of lymphocytes that react against the central nervous system. Fingolimod is lipophilic and readily crosses the blood-brain barrier and may act as a neuroprotective or reparative agent.2 The S1P receptor also plays a role in regulating vascular permeability and there is strong evidence that S1P plays a role in promoting endothelial barrier integrity.3 This mechanism of action provides a theoretical basis for the macular edema that can be observed with fingolimod.

In the phase III TRANSFORMS and FREEDOMS clinical trials, there were 13 of 2,564 (0.5%) patients that developed macular edema. Only two of these patients were taking the 0.5mg dose approved by the FDA, while the others were taking a higher dose (1.25-5mg).3 The macular edema resolved on cessation of the drug. In these cases the macular edema was unilateral.

A recent case series of three patients includes the first case reported of bilateral CME associated with fingolimod.4 All the patients in this series were treated with the 0.5mg dose. Two of these patients had resolution with cessation of the drug. The third patient was treated with nepafenac, similar to our patient, and difluprednate with resolution of the CME. In this series, the patient with bilateral disease had a history of well-controlled diabetes with a hemoglobin A1C of 6.1.

In another study looking at early clinical experience with fingolimiod, 3 out of 317 patients developed CME, including one patient with concurrent diabetes. All three patients were over the age of 50 and the macular edema occurred in the first four months of treatment.5

Microcystic edema of the macula has also been noted in multiple sclerosis patients without uveitis and without a history of treatment with fingolimod.6 This study found 15 of 318 (4.7%) of MS patients with macular edema. More than half of these patients had a history of prior optic neuritis and subsequent letters to the editor wondered if the optic neuritis may have been the causative factor and suggest other instances where macular edema was seen after optic nerve pathology.7, 8

Our patient had never had an episode of optic neuritis, never had any signs of inflammation and developed his CME soon after starting fingolimod, leading to the conclusion that his CME was due to his medication use. He had not had any prior ocular surgery and did not have any stigmata of retinitis pigmentosa. He did not have any signs of vascular conditions related to CME. He did not have any tumors on careful examination of the remainder of his fundus. Because he has not had any signs of active inflammation while we have been following his CME, it is unlikely that his CME has an uveitic cause. This patient adds to the number of multiple sclerosis patients found to have CME related to fingolimod use. There are twenty such patients in the literature at this point, however, as this drug is used more frequently we will continue to see this complication.

Take Home Points

- Gilenya (fingolimod) is associated with cystoid macular edema that typically develops within four months of starting treatment.

- The cystoid macular edema associated with Gilenya use resolves with cessation of the drug.

- Treatment with topical nepafanac may be sufficient to control the CME and allow continuation of Gilenya.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010. 362: 402-415.

- Kappos L, Radue EW, O’Connor P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010. 362: 387-401.

- Jain N, Bhatti MT. Fingolimod-associated macular edema: incidence, detection and management. Neurology. 2012. 78: 672-680.

- Afshar AR, Fernandes JK, Patel RD, et al. Cystoid macular edema associated with fingolimod use for multiple sclerosis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013. 131: 103-107.

- Ontaneda D, Hara-Cleaver C, Rudick RA, et al. Early tolerability ad safety of fingolimod in clinical practice. Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2012. 323: 167-172.

- Gefland JM, Nolan R, Schwartz DM, et al. Microcystic macular oedema in multiple sclerosis is associate with disease severity. Brain. 2012. 135: 1786-1793.

- Abegg M, Zinkernagel M, Wolf S. Microcystic macular degeneration from optic neuropathy. Brain. 135: e225.

- Balk LJ, Killestein J, Polman CH, et al. Microcystic macular oedema confirmed, but not specific for multiple sclerosis. Brain. 135: e226.