West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

March, 2014

Presented by Sara Haug, MD, PhD

16-year-old female presents with decreased vision in left eye for one month

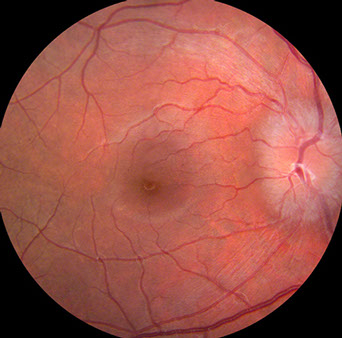

A

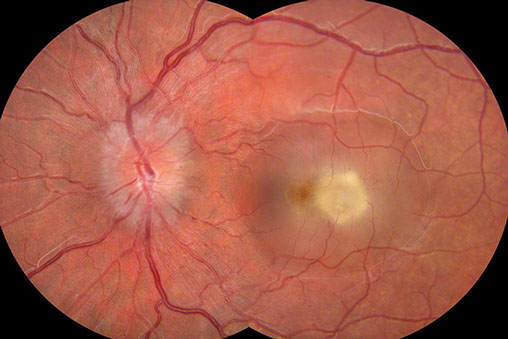

B

Figures 1A and B: Color fundus photographs of the right (A) and left (B) posterior pole. On the right (A), the optic disc is hyperemic with blurred disc margins. The macula is normal. On the left (B), the optic disc is swollen and hyperemic and temporal to the fovea is a creamy subretinal lesion with surrounding subretinal fluid

Case History

A 16-year-old female presents with a chief complaint of decreased vision in her left eye for approximately one month. Her past medical history is notable for HIV+ status since birth. The patient had recently stopped taking her anti-retroviral therapy and her last CD4 count had decreased to 17 with an elevated viral load at approximately 80,000. She was diagnosed with cryptococcal meningitis two months prior to presentation. This was treated, initially with intravenous ambisome (liposomal amphotericin) followed by oral fluconazole, which the patient was still taking at the time of presentation of her ocular symptoms. Her course of intravenous therapy was complicated by fevers. Her central intravenous line was removed and diagnostic procedures were initiated. Penicillin was added to her medication regimen, and her fevers subsequently subsided. Additionally, the patient was restarted on antiviral and prophylactic medicines: epivir, kaletra, viread, and inhaled pentamidine. She takes no other medicines.

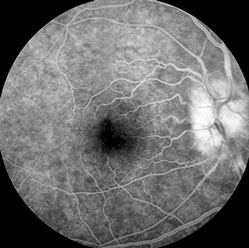

On physical examination, her vision is 20/20- OD and 20/250 OS. Intraocular pressures are 10 bilaterally. Pupillary reactions are symmetric and without afferent defect. Slit lamp examination of the anterior segment is unremarkable in both eyes, with quiet anterior chambers and clear media. Dilated fundus examination reveals hyperemic discs with hazy borders bilaterally, consistent with papilledema. Additionally her left posterior pole shows a creamy yellow subretinal lesion, almost one disc diameter in size. There is extensive subretinal fluid surrounding the lesion. (Figure 1) Fluorescein angiography confirms the size of the lesion and reveals early hyperfluorescence with late leakage (Figure 2).

A

B

C

Figures 2A-C: Fluorescein angiography of the right (A) and left (B and C) fundus. The mid-phase fluorescein angiogram on the right shows hyperfluorescence of the nerve and a normal macula (A). Figure B is a late laminar phase fluorescein angiogram of the left eye showing a hyperfluorescent optic nerve and a hyperfluorescent lesion of about 1 disc diameter just temporal to the fovea. In later frames (C) , the angiogram reveals subretinal fluid surrounding the hyperfluorescent lesion and including the fovea.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis and Clinical Course

The differential diagnosis is most concerning for infectious etiology. Fungal causes include Cryptococcus (particularly considering the patient’s recent history of cryptococcal meningitis), Candida, Aspergillus, Pneumocystis, or Coccidioides. Bacterial and viral causes are also on the differential, such as Cytomegalovirus or other herpes viruses, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, or Syphilis. Toxoplasma must be considered as well as lymphoma.

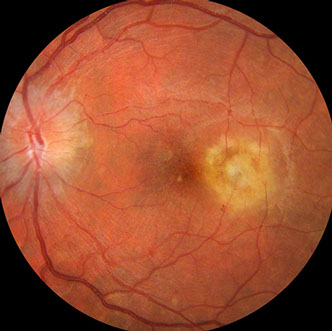

Gram stain was done on a vitreous sample and revealed gram-positive, aerobic filamentous rods (Figure 3), which narrowed the differential diagnosis to Lactobacillus, Nocardia, Actinomyces, or Cryptococcus. Blood culture confirmed the diagnosis of Nocardia asteroides. The patient was started on intravenous imipenem/cilastatin every eight hours and then transitioned to oral antibiotic therapy. Two weeks following treatment, the lesion appeared less active and the subretinal fluid had improved (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Gram stain showing Nocardia asteroides, with gram positive, delicate filaments and pronounced branching patterns.

Figure 4: Color fundus photograph of the left macula. The nerve appears less swollen than on initial presentation (Figure 1) and the temporal lesion appears less active. The subretinal fluid has also improved.

Discusion

Nocardia is a partially acid-fast, aerobic, filamentous rod that is ubiquitous in the environment, found in soil and vegetation.1 Most commonly associated with pulmonary infections in immunocompromised patients, nocardiosis has also been reported in association with cerebral invasion and life-threatening systemic dissemination. Ocular infection by Nocardia is rare and most are acquired exogenously.2 The cornea is the most common site of ocular infection, reported after accidental and surgical trauma including refractive surgery, but Nocardia has also been found to cause scleritis, conjunctivitis, canaliculitis, dacryocystitis, orbital cellulitis, and exogenous or endogenous endophthalmitis.1 Of those patients with Nocardia bacteremia, 3-5% will have a focus in the eye.3

A recent survey article analyzed all published cases of Nocardia endogenous endophthalmitis in the literature since 1967 and found only forty-seven reported cases.4 In their analysis, the authors report over half of the patients first sought medical attention because of ocular symptoms, most commonly blurred vision but 41% also had ocular pain. Three-fourths of cases were unilateral. Fundus examination revealed over two-thirds of cases had one single lesion described as a mass, an inflammatory mass, or chorioretinal exudate, very similar to the case presented here. Superficial or intraretinal hemorrhages were often associated4, although no hemorrhage was noted in our patient. The macula was often involved (69%) and one-third of eyes developed serous retinal detachment.4 Nocardia endogenous endophthalmitis portends a poor prognosis; in the survey article they noted the mortality rate over a two year period was 27%.4

If endogenous Nocardia infection is suspected, it is important to perform a gram stain and culture on a vitreous sample, either from a vitreous tap or from pars plana vitrectomy. A fine needle aspirate of the subretinal lesion can be considered in the case of an isolated subretinal abscess. However, if another organ system is involved, consider first doing a diagnostic biopsy elsewhere. Systemic treatment of the bacteremia is typically sufficient to treat the ocular disease. Cases in which the fluorescein angiogram demonstrates late leakage into the vitreous from a chorioretinal focus, intravitreal antibiotics or therapeutic pars plana vitrectomy can be considered.4 The appropriate antibiotic is typically chosen based on minimal inhibitory concentration analysis performed on the organism, but can include ceftriaxone, amikacin, linezolid, and imipenem.5,6 Early identification of Nocardia bacteremia and endogenous endophthalmitis allows for early intervention of life-saving treatment.

Take Home Points

- Nocardia is a rare cause of ocular infection, usually acquired exogenously.

- 3-5% of patients with Nocardia bacteremia will have a ocular involvement.

- Early diagnosis, usually through vitreous biopsy, can result in initiation of life-saving treatment.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Garg P. Fungal, mycobacterial, and Nocardia infections and the eye: an update. Eye 2012;26:245-51.

- Scott M, Mehta S, Rahman HT. Nocardia veteran endogenous endophthalmitis in a cardiac transplant patient. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect 2012;2:141-3.

- Bullock JD Encogenous ocular nocardiosis: a clinical and experimental study Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1983;81:451-531.

- Eschle-Meniconi ME, Guex-Crosier Y, Wolfensberger TJ. Endogenous ocular nocardiosis – an interventional case report with a review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol 2011;56:383-415.

- Acar JF, Goldstein FW, Kitzid MD, et al. Activity of imipenem on aerobic bacteria. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1983;12:37-45.

- Adenis JP, Mounier M, Salomon JL, et al. Human vitreous penetration of imipenem. Eur J Ophthalmol 1994;4:115-7.