West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

May, 2012

A 64-year-old man with a 2 week history of blurred vision in both eyes.

Presented by Paul Stewart, MD

A

B

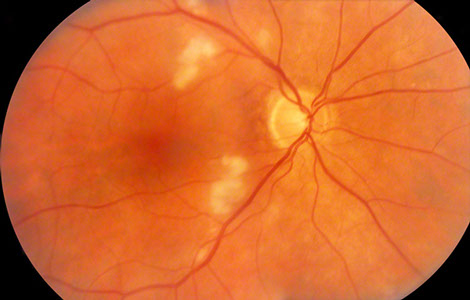

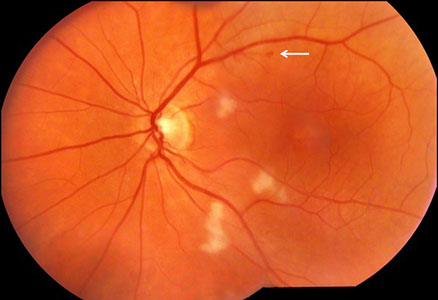

Figures 1A and B: Color photographs of the right and left eye. Note multiple cotton wool spots in each eye. The right macula appeared normal, but mild mottling of the retinal pigment epithelium was present in the left macula. A small retinal hemorrhage was apparent along the superotemporal arcades (arrow).

Case History

A 64-year-old man presented with a two-week history of bilaterally decreased vision that started immediately following a radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. The surgery was without complication and he had a routine recovery. He was otherwise in good health. His visual acuity was 20/32 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye.

Fundus examination of the right eye (Figure 1A) showed clear ocular media. The optic nerve was healthy. There were multiple cotton wool spots in the posterior pole. On fluorescein angiography (Figure 2), there was staining of the cotton wool spots.

Fundus examination of the left eye (Figure 1B) showed clear ocular media. The optic nerve was healthy. There were multiple cotton wool spots in the posterior pole and retinal pigment epithelial mottling near the fovea. On fluorescein angiography (Figure 3), there was staining of the cotton wool spots and faint cystoid macular edema.

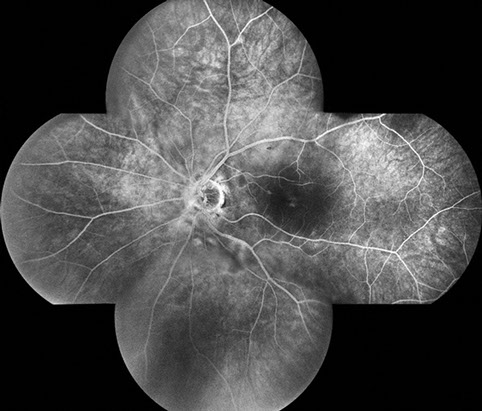

A

B

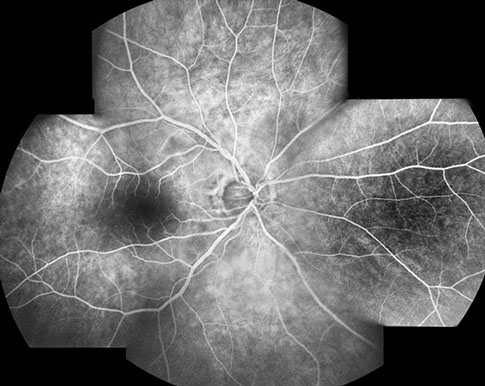

Figures 2A and B: Fluorescein angiography montage and late phase angiogram of the right eye. Note that the retinal vasculature appears to fill normally and the late phase views show leakage in the posterior pole in the area of the cotton wool spots and surrounding retina.

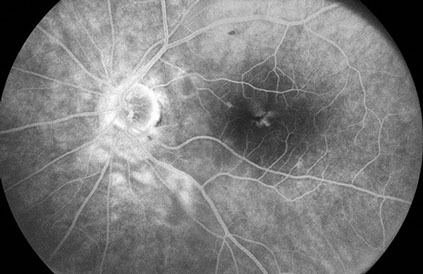

A

B

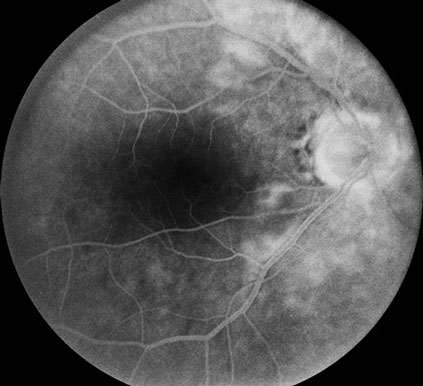

Figures 3A and B: Fluorescein angiography montage and late phase angiogram of the left eye. The retinal vessels fill normally, and the area of the cotton wool spots and surrounding retina leak similar to the right eye. Mild macular edema appears to be present as well.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis: Circumpapillary Cotton Wool Spots

- Acute pancreatitis

- Diabetic retinopathy

- Hypertensive retinopathy

- Radiation retinopathy

- Interferon retinopathy

- HIV retinopathy

- Long bone fracture/orthopedic surgery

- Chest compression injuries

- Chronic renal failure

- Hemolytic uremic syndrome

- Childbirth

- Connective tissue disorders; most commonly systemic lupus erythematosus

- Cryoglobulinemia

- Weight-lifting

- Shaken baby syndrome

- Retrobulbar and periocular injections

- Valsalva maneuver

- Commotio retinae

- Multiple myeloma

Discussion

Purtscher first described the condition that bears his name in 1910 in a patient with head trauma from a fall. He described areas of bilateral retinal whitening and hemorrhage. Vision recovered without treatment.

The vision loss associated with Purtscher’s retinopathy typically occurs within a day or two of the insult, and can range from minimal to profound. Scotomata are common and may be central, paracentral or arcuate. The cotton wool spots of Purtscher's retinopathy, also known as Purtscher flecken, cluster around the disc and are typically found between the retinal venules and arterioles – with a characteristic clear zone observed adjacent to the arterioles. In addition to cotton wool spots, fundus examination can reveal intraretinal hemorrhages, optic disc swelling, and, in severe cases, a cherry red spot.

Fluroescein angiography and indocyanine green angiography typically show variable degrees of retinal and choroidal non-perfusion, respectively. Optical coherence tomography can show both swelling of the nerve fiber layer and disruption of the IS/OS junction.

The exact pathogenesis of the retinal findings observed in Purtscher’s retinopathy is unknown, but is believed to involve embolic occlusion of the precapillary arterioles, which measure approximately 50 microns in diameter. Potential emboli include air, fat, leukocyte aggregates, platelets and fibrin, depending on the inciting factor. It has been postulated that intravascular lipase and complement activation might promote local leukocyte aggregation, thus further promoting small vessel occlusion.

Vision recovery varies and appears to depend most directly on the degree and extent of retinal and choroidal non-perfusion. High dose intravenous corticosteroids have been used in the acute setting with variable results. Plasmapheresis has been suggested to be effective in selected patients with active systemic vasculitis, most notably systemic lupus erythematosus.

To our knowledge, Purtscher’s retinopathy has not been reported following prostate surgery. It is possible that complement activation related to the surgery could have resulted in the retinal findings and visual symptoms in our patient. Prospective studies evaluating complement activation following rectal surgery for cancer have shown a significant increase in the alternative pathway activation of complement with the terminal C5b-9 complex reaching peak levels 3-5 days after surgery. This timing may indicate why the visual symptoms of Purtscher’s often happen a day or two after the initial insult. It should be noted, however, that other studies have shown no increased complement activation in other types of surgery, including abdominal and laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Take Home Points

- Purtscher’s retinopathy after radical prostatectomy gives further credence to the hypothesis that the characteristic retinal findings may be related to complement activation.

- Purtscher’s retinopathy typically resolves without treatment.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Agrawal A and McKibbin MA. “Purtscher’s and Purtscher-like Retinopathies: A Review,” Survey of Ophthalmology. 51:2, 2006, 129-136.

- Burton TC. “Unilateral Purtscher’s retinopathy,” Ophthalmology. 87, 1980, 1096-1105.

- Wang AG, Yen MY, Liu JH. “Pathogenesis and neuroprotective treatment in Purtscher’s retinopathy,” Jpn J Ophthalmol. 42, 1988, 318-322.

- Beckingsale AB, Rosenthal AR. “Early fundus fluorescein angiographic findings and sequelae in traumatic retinopathy: a case report,” Br J Ophthalmol. 67, 1983, 119-123

- Gomez-Ulla F, Fente B, Torreiro MG, et al. “Choroidal vascular abnormality in Purtscher’s retinopathy shown by indocyanine green angiography,” Am J Ophthalmol. 122, 1996, 261-263.

- Behrens-Baumann W, Scheurer G, Schroer H. “Pathogenesis of Purtscher’s retinapathy. An experimental study,” Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 230, 1992, 286-291

- Harrison TJ, Abbasi CO, Khraishi TA. “Purtscher retinopathy: an alternative etiology supported by computer fluid dynamic simulations,” Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 52: 11, 2011, 8102-8107.

- Atabay C, Kansu T, Nurlu G. “Late visual recovery after intravenous methylprednisolone treatment of Purtscher’s retinopathy,” Ann Ophthalmol. 25, 1993, 330-333.

- Hollo G, Tarjanyi M, Varga M, et al. “Retinopathy of pancreatitis indicates multiple-organ failure and poor prognosis in severe acute pancreatitis,” Acta Ophthalmol. 72, 1994, 114-117.

- Shein, J, Shukla D, Reddy S, Yannuzzi LA, Cunningham ET Jr. “ Macular infarction as a presenting sign of systemic lupus erythematosus.” Retina Cases & Case Series 2008, 2:55-60.

- Kvarnstrom A, Sokolov A, Swartling T, et al. “Alternative pathway activation of complement in laparoscopic and open rectal surgery.” Scand J Immunol. 2012, April 4, Epub ahead of print.

- Xu C, Jung M, Burkhardt M, et al. “Increased CD59 protein expression predicts a PSA relapse in patients after radical prostatectomy.” Prostate, 62, 2005, 224-32.