West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

May, 2016

Presented by Ananda Kalevar, MD

A 43 year-old man presents with blurred vision in his left eye.

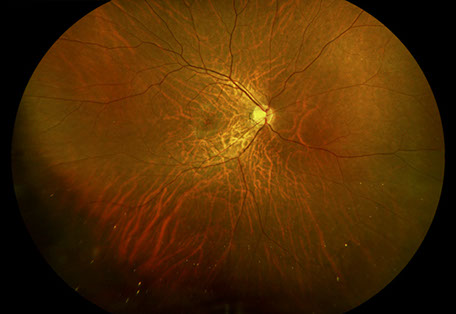

A

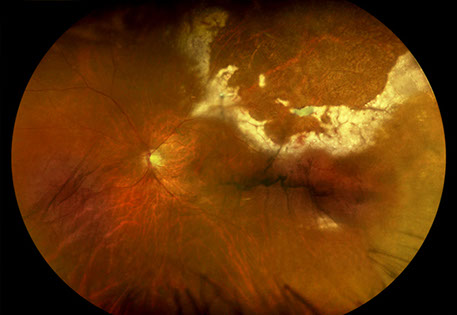

B

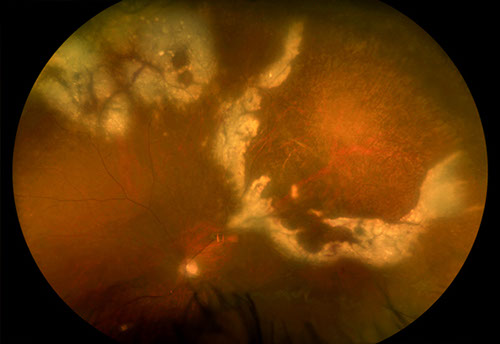

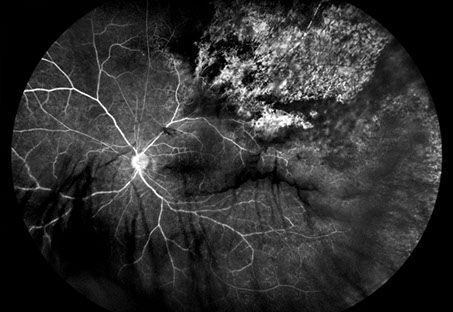

Figures 1A-C: Wide field color fundus photographs of his right (A) and left (B, C) eyes. Retinal hemorrhages with sheathed vessels in the periphery of the right eye. White retinitis admixed with necrosis and hemorrhage along with sheathed vessels in the periphery of the left eye.

Case History C

C

A 43 year-old homosexual man presents with blurred vision in his left eye along with floaters and an inferior field loss. His past medical history, ocular history, family history and medications were non-contributory.

On examination, best-corrected visual acuity was 20/40 and 20/60 in the right and left eye, respectively. Intraocular pressure was normal in both eyes. The anterior segment examination was remarkable for anterior chamber inflammation in both eyes, more prominently seen in the left eye. Similarly, vitreous cells were seen more so in the left eye than the right eye. The posterior segment exam in the right eye was remarkable for retinal hemorrhages with sheathed vessels in the periphery (Figure 1A). In the posterior segment in the left eye, areas of white retinitis admixed with necrosis and hemorrhage are seen in the periphery with sheathed vessels (Figure 1B and C). No retinal tears or detachments were appreciated in either eye.

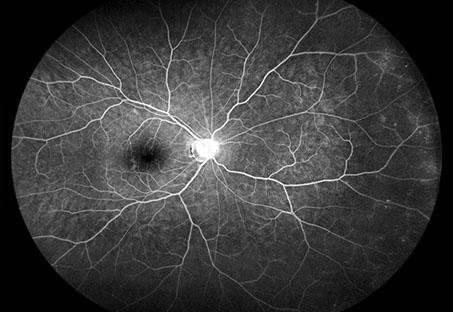

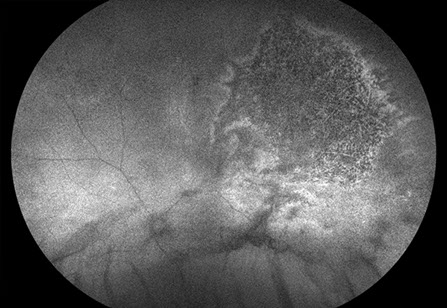

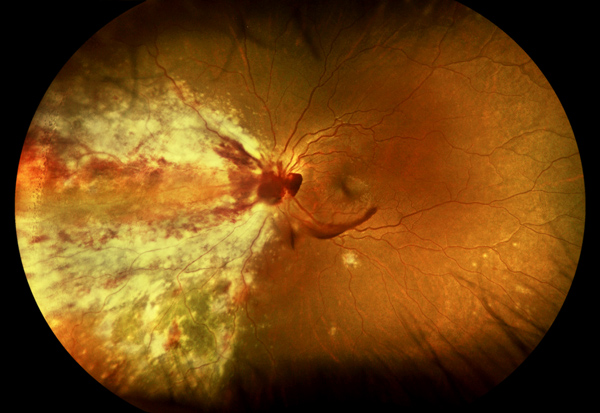

Spectral domain OCT of the macula were unremarkable in both eyes. Fluorescein angiography revealed peripheral vascular leakage in the right eye and in the left eye (Figures 2A and B). In addition in the left eye, early hypofluorescence consistent with necrosis with late hyperfluorescence. Fundus autofluorescence of the right eye was unremarkable and that of the left eye shows peripheral speckled hyperautofluorescence surrounding an area of hypoautofluorescence superotemporally (Figure 3).

A

B

Figures 2A-B: Wide field fluorescein angiography of his right (A) and left (B) eyes. Peripheral vascular leakage seen in both eyes. Early hypofluorescence consistent with necrosis with late hyperfluorescence seen in the periphery of the left eye.

Figure 3: Wide field fundus autofluorescence of his left eye. Speckled hyperautofluorescence surrounding an area of hypoautofluorescence seen in periphery of left eye.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential diagnosis

Cytomegalovirus retinitis, Herpes simplex retinitis, Herpes Zoster retinitis, Toxoplasmosis, Sarcoidosis, Syphilis, Tuberculosis, endogenous endophthalmitis, intermediate uveitis, Behcet’s disease

Additional Case History

Laboratory evaluation confirmed that he was HIV positive, while the remaining uveitis evaluation was unrevealing. PCR testing of aqueous fluid revealed CMV.

Discussion

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients. CMV retinitis is the most common ocular opportunistic infections in patients with AIDS. When highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was not available for patients, CMV retinitis developed in approximately of 30% of patients at one point during their lifetime.1 With the introduction of HAART, the incidence of CMV retinitis decreased by 75%.2 Currently, patients with unrecognized diagnosis of HIV infection or those who are noncompliant, intolerant or unresponsive to HAART have the highest risk to develop CMV retinitis.3 The highest risk factor to develop CMV retinitis was a CD4+ T cell count below 50 cells/microliter.2 Though the majority of CMV retinitis cases occur in the setting of AIDS, it can also be seen in HIV-negative patients who possess a factor that contributes to a decline in their overall immune function such as advanced age, underlying malignancy (Figure 4), autoimmune disease, systemic immunosuppression, ocular corticosteroids, diabetes mellitus or an immune disorder.4

CMV is a necrotizing retinitis that progresses slowly. It can be a unilateral or bilateral entity that affects either the periphery, the posterior pole or both. The classic clinical picture appears a white intraretinal infiltrate with prominent hemorrhage seen at the edge of the lesion. As the retinitis advances, atrophic avascular retina with pigmentary changes are seen. Though presentation can vary for each patient and present as retinal edema, perivascular sheathing and exudative retinal detachment. Wide angle imaging can be particularly helpful in diagnosing and monitoring progression in CMV retinitis.3

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment was a common finding in CMV retinitis in the pre-HAART era, with incidences being approximately 33% per eye per year. This rate has decreased by 60% with HAART.3 Retinal detachment typically occur due to breaks in healed atrophic areas or active areas of necrosis.

Screening for CMV retinitis is particularly difficult. Urine and blood cultures are not reliable to confirm the diagnosis of CMV retinitis. A PCR of an intraocular sample is the most specific and sensitive manner to confirm the diagnosis.

CMV retinitis can be treated systemically, locally or a combination of the two.3 Systemically, the options are oral valganciclovir or intravenous foscarnet or intravenous cidofovir. Ganciclovir, foscarnet, cidofovir are intraocular options.

Figure 4: Wide field color fundus photograph of the left eye of a HIV negative 18 year old with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who presented with CMV retinitis.

Take Home Points

- CMV necrotizing retinitis is most commonly seen in HIV patients.

- There is a high risk of retinal detachment in these cases.

- Multiple treatment options exist, most commonly PO Valganciclovir.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Hoover DR, Peng Y, Saah A, Semba R, Detels RR, Rinaldo CR, Phair JP. Occurrence of cytomegalovirus retinitis after human immunodeficiency virus immunosuppression. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1996 Jul 1;114(7):821-7.

- Sugar EA, Jabs DA, Ahuja A, Thorne JE, Danis RP, Meinert CL, Studies of the Ocular Complications of AIDS Research Group. Incidence of cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. American journal of ophthalmology. 2012 Jun 30;153(6):1016-24.

- Ryan S. Retina, 5th ed. 2013: 1444-1458.

- Downes KM, Tarasewicz D, Weisberg LJ, Cunningham ET. Good syndrome and other causes of cytomegalovirus retinitis in HIV-negative patients—case report and comprehensive review of the literature. Journal of ophthalmic inflammation and infection. 2016 Jan 25;6(1):1.