West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

November, 2012

A 68-year-old woman referred for evaluation of mass in her left eye

Presented by Paul Stewart, MD

Figure 1: Color fundus photo montage of the left eye with an amelanotic lesion with sharply defined borders along the superotemporal arcade.

Case History

A 69-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a mass lesion in the fundus of the left eye. This lesion had been noted five years earlier and was thought by the referring physician to have increased slightly in thickness, but otherwise had been stable. The patient had a history of stage II diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with abdominal adenopathy, treated with chemo (R-CHOP) six years ago without evidence of recurrence after treatment. Her past medical history was otherwise unremarkable.

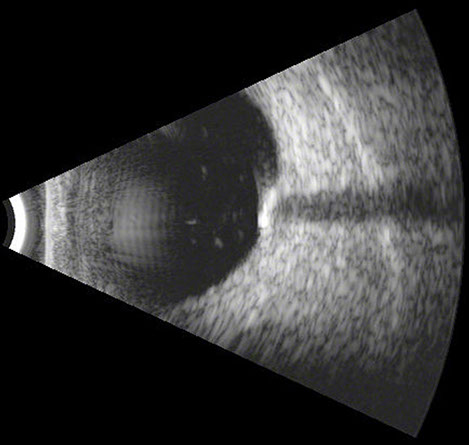

On examination the patient had 20/16 vision in the right eye and 20/25 vision in the left eye. Intraocular pressures and anterior segment examinations were normal in both eyes. The fundus examination of the right eye was unremarkable. Fundus examination of the left eye showed a white and orange triangular lesion with sharply defined borders along the superotemporal arcade (Figure 1). B-scan ultrasonography showed a minimally elevated hyperechoic lesion with dense posterior shadowing (Figure 2).

Figure 2: B-scan ultrasonography with a minimally elevated hyperechoic lesion with dense posterior shadowing.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of amelanotic mass lesions includes: choroidal melanoma, choroidal metastasis, choroidal osteoma, choroidal nevus, intraocular lymphoma, retinal astrocytic hamartoma, choroidal hemangioma, eccentric macular degeneration, choroidal granuloma, sclerochoroidal calcification, metastatic sclerochroidal calcification, chorioretinits and regressed retinoblastoma. Many of these entities can be differentiated based on exam, and adjunctive studies such as fluorescein angiography and ultrasonography.

Discussion

Sclerochoroidal calcification is most commonly seen in middle-age and elderly individuals as an idiopathic finding. Younger patients with sclerochoroidal calcifications frequently have associated systemic conditions. At the earliest phase there may only be ultrasonographic or CT evidence of sclerocalcification. Later there may be overlying chorioretinal atrophy.1 Typical fundus findings of sclerochoroidal calcification include a solitary yellow lesion along the superior or inferior arcades.2 Lesions may be bilateral in 40-80 percent of cases and can be multifocal half the time. On ultrasound the lesions are densely echogenic with posterior shadowing. On fluorescein angiography the lesions show mild hypofluorescence early and late staining.

Although most cases of sclerochoroidal calcification are idiopathic, a number of systemic abnormalities involving calcium or magnesium metabolism have been associated.3 Bartter and Gitelman syndromes are characterized by sodium and potassium wasting due to genetic mutations involving electrolyte transport in the renal tubules.4 There is a neonatal form that is associated with polyhydramnios, premature delivery, hypercaciuria and failure to thrive. The classic Bartter syndrome shows polyuria, polydipsia, and hypokalemic metabolic acidosis. Gitelman syndrome has chondrocalcinosis, hypokalemic alkalosis, hypomagnesemia and hypocalciuria. Sclerochoroidal calcifications have been associated with hyperparathyroidism, occasionally resulting from a parathyroid adenoma.5 Prior scleral inflammation has also been implicated in sclerochroidal calcifications.6

The majority of patients with sclerochroidal calcifications are asymptomatic. Occasionally choroidal neovascular membranes may develop, requiring treatment. This entity is readily recognized if the clinician is aware of it and pursues appropriate testing.

Take Home Points

- Sclerochoroidal calcification are benign lesions with an excellent prognosis.

- Ultrasonographic findings and typical location within the eye are keys to the correct diagnosis.

- Most cases are idiopathic, but systemic causes should be considered, particularly when present in younger individuals.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Hara K, Tanito M, Kodama T, Ohira A. A case of chorioretinal atrophy due to sclerochoroidal calcification. Acta Ophthalmol. June 2012.

- Honavar SG, Shields CL, Demirci H, Shields JA. Sclerochoroidal calcification. Arch Ophthalmol. Vol 119, June 2001, 833-840.

- Sun H, Demirci H, Shields CL, Shields JA. Sclerochoroidal calcification in a patient with classic Bartter’s Syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. Vol. 139, Feb 2005, 365-366.

- Fremont OT, Chan JC. Understanding Bartter Syndrome and Gitelman Syndrome. World J Pediatr. Feb 2012, 25-30.

- Goldstein BC, Miller J. Metastatic calcification of the choroid in a patient with primary hyperparathyroidism. Retina. 1982, 76-79.

- Saatci AO, Kaynak S, Kazanci L, Durak I, Tunc M. Calcification at the posterior pole in scleritis. A case report. Ophthalmologica. 1996, 285-287.