West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

November, 2013

Presented by Sara Haug, MD, PhD

52-year-old woman presents with blurred vision in both eyes for two months

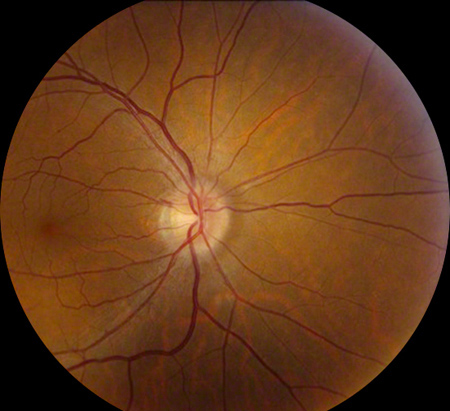

A

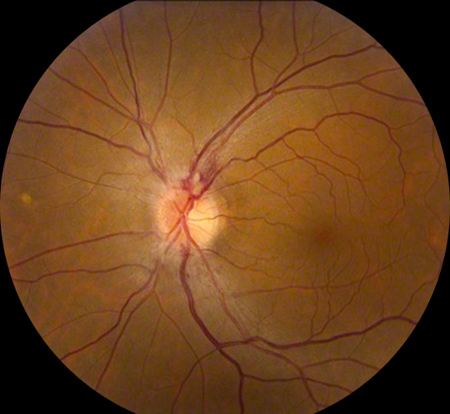

B

Figures 1A and B: Color fundus photography of the right (A) and left (B) optic nerve and macula. Note the subtle optic disc edema in the right eye. It is much more apparent in the left eye. Peripapillary flame-shaped hemorrhage is present superiorly.

Case History

A 53-year-old woman with a complicated medical history presents with blurry vision in both eyes for the past two months. She was in car accident 18 months prior to presentation and subsequently developed new headaches. An MRI of the brain done at that time was negative. One year after the car accident, the patient developed vertigo with tinnitus and a CT scan showed an enlarged vestibular aqueduct on the right. The patient went on to lose hearing in her right ear. The vertigo, hearing loss, and headaches persisted and the patient was treated with nortriptyline.

Two months prior to presentation, and 16 months following the car accident, the patient developed blurry vision in both eyes. One month later, the patient noticed a new black spot in her left eye. Ophthalmic exam at that time showed optic disc edema on the left. The patient was started on Prednisone orally 100mg per day given concern for giant cell arteritis and a temporal artery biopsy was recommended. C-reactive protein level was 0.5 and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate at its peak was 46. In addition the patient reported hearing a heartbeat in her head. Prior to the car accident, the patient was healthy with no medical problems.

On presentation, visual acuity was 20/25 in both eyes. Intraocular pressure was 18 and 17 mmHg respectively and blood pressure was 131/86. Anterior segment examination was normal in both eyes except for mild lens changes. Posterior segment examination showed subtle optic disc edema nasally on the right with a small hemorrhage along the disk margin. On the left, there was obvious optic disc edema with flame hemorrhages. Fluorescein angiography was performed and showed optic nerve staining and leak in both eyes in the later frames (Figure 2).

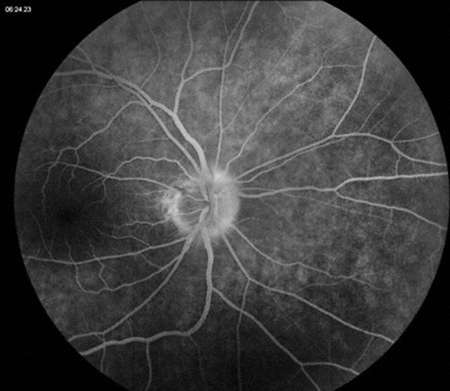

A

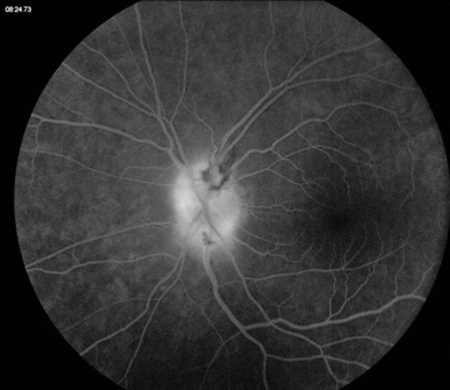

B

Figures 2A and B: Late fluorescein angiogram photos of the right (A) and left (B) optic nerve and macula. Late staining is present bilaterally, though more marked in the left eye.

What is your Diagnosis?

Diagnosis

Optic disc swelling can be caused by a number of different etiologies, including arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (giant cell arteritis), non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, an intracranial tumor or mass, or elevated intracranial pressure, either from obstructive hydrocephalus or idiopathic (pseudotumor cerebri). Diabetic or hypertensive papillitis can also cause optic disc edema.

In addition, there are a number of infectious causes of papillitis, including Lyme disease, syphilis, Bartonella henslae, and herpes zoster. Sarcoidosis has also been associated with hyperemic optic disc swelling. Buried optic disc drusen are another consideration, often misdiagnosed as optic disc edema. However, this is rarely associated with flame-shaped hemorrhages.

In this case, the optic disc edema was bilateral and associated with hearing loss, headache, and vertigo. The laboratory values for CRP and ESR were not diagnostic for giant cell arteritis. Given the constellation of symptoms, the patient was sent to a neuro-ophthalmologist, who performed a lumbar puncture and found elevated cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) opening pressure. The patient was given a diagnosis of pseudotumor cerebri.

Discusion

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a disorder characterized by isolated raised intracranial pressure not related to an intracranial disorder.1,2 The syndrome was first described by German physician Quincke in the 1890s and, in 1904, given the name ‘pseudotumor cerebri’ by Nonne.2,3 One of the pioneers of neurosurgery, Dr. Dandy, went on to describe the clinical course of 22 patients he encountered with this syndrome in the 1920s and it is an updated version of his diagnostic criteria used today.3

By definition, all patients with IIH will have signs and symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure but the modified Dandy Criteria are used to aid in diagnosis. The criteria include cranial imaging confirming the absence of radiographic hydrocephalus or mass lesion, elevated CSF opening pressure upon ventricular or lumbar spinal tap with normal CSF fluid profile, and intact neurological exam with the exception of visual disturbances, sixth cranial nerve palsy, and papilledema. The most common presenting symptoms are headache and blurred vision.3,4

IIH occurs primarily in women of childbearing years with a high body mass index or recent weight gain. Only 10% of patients with IIH are men, and men are often older at presentation compared to women with IIH.1 Given the increasing prevalence of obesity, the disorder is of increasing importance although the exact relationship between obesity and IIH remains poorly understood. Several etiological hypotheses have been proposed, including increased central venous pressure and various hormonal and metabolic changes commonly found in obese patients.1

There are two goals in the treatment of pseudotumor cerebri. The first is to alleviate symptoms of increased intracranial pressure, particularly headaches, and the second is to preserve vision, which is the major morbidity in this disorder. In many cases, IIH is a benign and self-limiting condition. In patients with mild headaches and stable vision, non-invasive management with diuretics and weight loss is often adequate.1,3 More recently, topiramate (Topamax) has been shown to decrease CSF production and has the added benefit of inducing weight loss.3 Serial high volume lumbar punctures have been advocated in the past as a management strategy for patients with elevated ICP, however this is not often used outside the acute phase of the syndrome.3

Despite the fact that IIH is usually self-limited, one-quarter of patients will continue to have visual deterioration and headaches despite medical management. These patients often benefit from surgical treatment, usually by placement of a lumbar-peritoneal shunt.1,3,4

Take Home Points

- Pseudotumor cerebri, or idiopathic intracranial hypertension, is increasingly common as obesity rates continue to rise.

- If IHH is suspected, the first step is to obtain either a CT or MRI scan of the brain to rule out a mass lesion and hydrocephalus, followed by a lumbar puncture.

- Most patients with IIH have a self-limited course and can be managed conservatively with diuretic treatment and weight loss.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Biousse V, Bruce BB, Newman NJ. Update on the pathophysiology and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;83:488-94.

- Fraser C, Plant GT. The syndrome of pseudotumour cerebri and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Curr Opin Neurol 2011;24:12-17.

- Galgano MA, Deshaies EM. An update on the management of pseudotumor cerebri. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2013;115:252-9.

- Daniels AB, Liu GT, Volpe NJ, et al. Profiles of obesity, weight gain, and quality of life in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri). Am J Ophthalmol 2007;143:635-41.