West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

October, 2012

A 47-year-old man with decreased vision in both eyes.

Presented by Sara Haug, MD, PhD

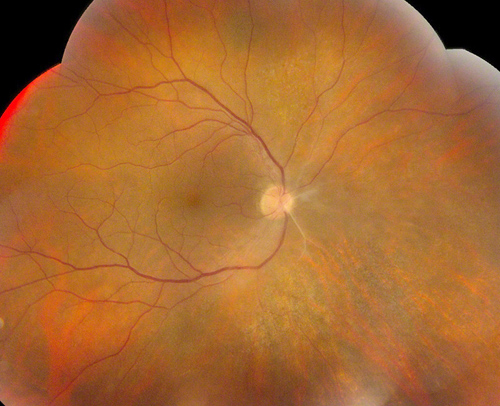

Figure 1: Color fundus photograph montage of the right eye. There is mild inflammation with sclerotic vessels off the optic disc nasally

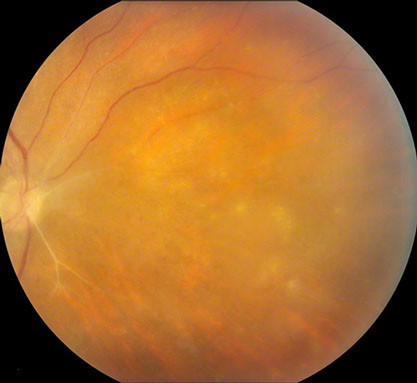

Figure 2: Color fundus photograph of the right eye, nasal view. The sclerotic vessels off the nasal aspect of the nerve are noted as well as scattered patches of retinitis.

Case History

The patient was a 47-year-old Caucasian man was referred with bilaterally decreased vision, worse on the left. He had no prior medical or ocular history. Best-corrected vision was 20/160 in the right eye and 10/200 in the left eye with intraocular pressures of 14mm Hg and 12mm Hg, respectively. Anterior segment examination on the right showed circumlimbal injection and one cell per high-powered field in the anterior chamber. There were scattered anterior vitreous cells. On the left, anterior segment examination showed 2 – 4 cells per high-powered field with two posterior synechiae and scattered anterior vitreous cells. Posterior examination on the right showed mild vitreous cells, sclerotic arterioles off the nasal aspect of the optic disc, and patchy areas of retinitis in the mid-periphery (Figs 1 & 2). Posterior segment examination on the left showed moderately severe vitreous inflammation with limited view of the retina (Fig. 3). An area of retinitis was visible in the far superonasal periphery.

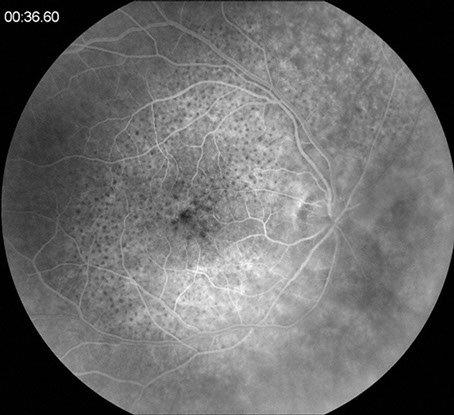

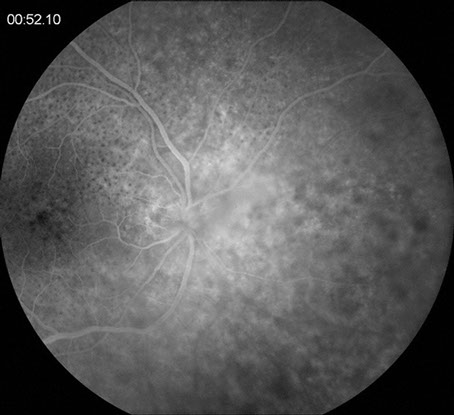

Fluorescein angiogram showed a circular area of leopard-spot hyperfluorescence involving the right macula, delayed filling of the sclerotic arterioles noted on clinical examination, and late leakage from the disc and large vessels bilaterally. The vitreous haze on the left limited interpretation of the fluorescein angiogram on that side.

Figure 3: Color fundus photograph montage of the left eye. There is moderately severe vitreous inflammation limiting visualization of the retina. An area of retinitis was noted in the superonasal periphery (not imaged).

A

B

Figures 4A & B: Fluorescein angiography of the right eye. Figure 4A shows macular leopard-spot hyperfluorescence. Figure 4B highlights the leakage from the disc and large peripapillary vessels.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes acute retinal necrosis (ARN), syphilitic uveitis, and toxoplasmosis. Tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and Behcet’s syndrome must also be considered. Masquerade syndromes such as intraocular lymphoma also need to be considered.

Clinical Course

The patient was treated with intravenous penicillin for presumed neurosyphilis. In addition, a course of oral prednisone was given, starting at 60 mg/day with a slow taper. Prednisolone acetate every hour and cyclopentolate drops four times daily were also used.

Early in the treatment course, the patient had an acute drop of vision in the left eye. Examination revealed retinal detachment but the view was limited due to miosis and media opacity. B-scan ultrasonography confirmed a total retinal detachment in a funnel configuration. Retinal detachment repair was done urgently and included scleral buckle, lensectomy, vitrectomy, peeling of subretinal and preretinal membranes, endolaser and fluid/silicone oil exchange. At the time of surgery, the superior retina was found to be necrotic with multiple breaks. One month after surgery, the retina remained attached with a pinhole vision of 20/80 (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Color fundus photograph montage of the right eye following retinal detachment repair. The retina is attached with a large area of necrotic retina noted superior to the disc and two areas of traction inferiorly. The scleral buckle is evident nasally and superiorly.

Discussion

Syphilis is a chronic venereal disease caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. In the United States, the rates of syphilis have been increasing since 2000, particularly in HIV-positive patients and men who have sex with men.1-3 Early invasion of the central nervous system is thought to occur in many patients infected with syphilis. Therefore, eye involvement can occur at any stage of infection, although it is most commonly observed in secondary syphilis.3 Parenteral penicillin has been used successfully to treat patients with syphilis for over fifty years. No penicillin-resistant strains of Treponema pallidum have yet been documented.2

Several studies have reported exudative retinal detachment and retinitis associated with syphilitic uveitis.4-6 There are fewer cases in the literature documenting the presence of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment with ocular syphilis, however.7-9 In one report of two patients with syphilitic uveitis, all four eyes ultimately had rhegmatogenous detachment requiring surgical intervention. In each eye, the detachment occurred following resolution of the active retinitis. Similarly, in our case, the patient had already completed his course of penicillin and was on a steroid taper when the detachment occurred. Therefore this complication can happen later in the course of the disease.7

Rhegmatogenous detachments are also seen in other forms of uveitis and retinitis. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis can often have breaks at the junction between normal and affected retina or in areas of necrosis.7 One study also reported vitreoretinal traction and formation of a retinal tear with immune reconstitution uveitis induced by CMV retinitis.10 Acute retinal necrosis has a high rate of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment that progresses rapidly caused by retinal necrosis with holes. Toxoplasmosis has also been reported to infrequently lead to rhegmatogenous detachment.11

Take Home Points

- Syphilis infections are on the rise, particularly in men who have sex with men. HIV co-infection is common.

- Both exudative and rhegmatogenous retinal detachments may be observed in patients with ocular syphilis.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- KG Ganem. Neurosyphilis: A Historical Perspective and Review. CNS Neurosci Ther 2010;16:e157-68.

- EL Ho, Lukehart SA. Syphilis: using modern approaches to understand an old disease. J Clin Invest 2011;121:4584-92.

- AJ Aldave, King JA, Cunningham ET. Ocular syphilis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2001;12:433-41.

- JM Jumper, Machemer R, Gallemore RP, Jaffe GL. Exudative retinal detachment and retinitis associated with acquired syphilitic uveitis. Retina 2000;20:190-4.

- D Diaz-Valle, Allen DP, Sanchez AA, et al. Simultaneous bilateral exudative retinal detachment and peripheral necrotizing retinitis as presenting manifestations of concurrent HIV and syphilis infection. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2005;13:459-62.

- SW Pan, Yusof NS, Hitam WH, et al. Syphilitic uveitis: report of 3 cases. Int J Ophthalmol 2010;3:361-4.

- K Williams, Kirsch LS, Fussack V, Freeman WR. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachments in HIV-positive patients with ocular syphilis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 1996;27:699-705.

- MS Passo, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular syphilis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Ophthalmol 1988;106:1-6.

- JA Pournaras, Laffitte E, Guez-Crosier Y. Bilateral giant retinal tear and retinal detachment in a young emmetropic man after Jarish-Herxheimer reaction in ocular syphilis. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2006;223:447-9.

- KM Chaudhary, Lieberman RM. Immune reconstitution uveitis complicated by vitreoretinal traction and formation of a retinal tear. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2012;24:e44-6.

- Y Sidikaro, Silver I, Holland GN, Kreiger AE. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachments in patients with AIDS and necrotizing retinal infections. Ophthalmology 1991;98:125-35.