West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

October, 2014

A 13 year-old girl presents with 4 days of decreased vision

Presented by Steven Williams, MD

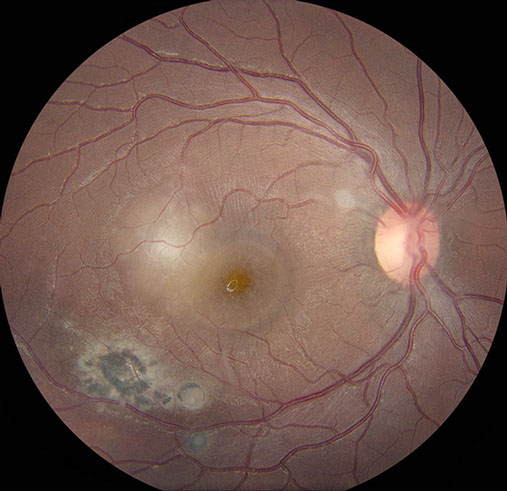

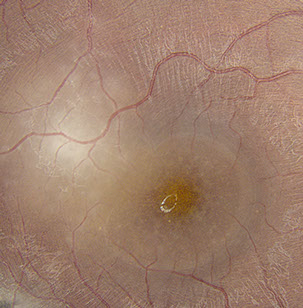

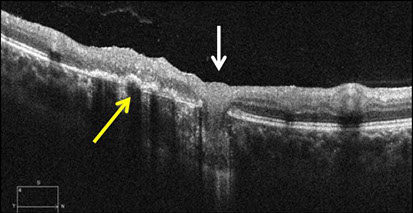

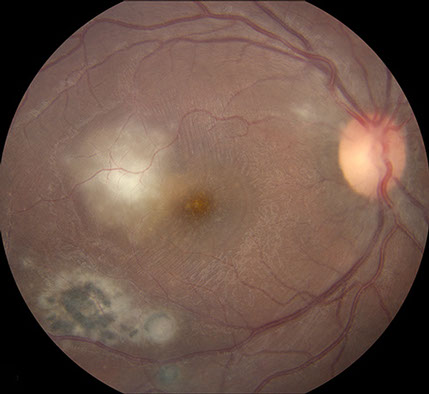

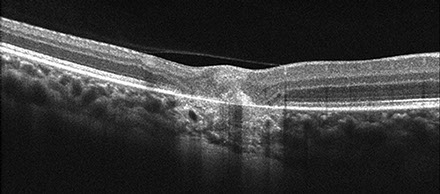

Figures 1: A: Fundus photograph of the right eye. Note the serous macular detachment and an area of active retinitis just superotemporal to the fovea. Chorioretinal scarring is present as well. B: Detail of inset showing punctate yellow-white spots are present within the fovea.

B

A

Case History

A thirteen year-old girl from El Salvador presented with four days of painless vision loss in her right eye. She also reported a viral illness three weeks prior to presentation, consisting of fever and cough, which resolved spontaneously. Past ocular and medical histories were unremarkable.

On examination, best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 8/200 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure and confrontation visual fields were normal bilaterally. Examination of the left eye was unremarkable. Anterior segment examination of the right eye revealed trace anterior chamber cell with no keratic precipitates. Posterior segment examination of the right eye revealed mild anterior vitreous cell and a normal appearing optic disc. A serous macular detachment was present, with yellow-white, punctate spots within the fovea, at level of the deep retina (Figure 1A). Supero-temporal to the fovea and adjacent to the detachment was an area of focal retinitis. Infero-temporally, there was an area of hyper-pigmented retinochoroidal scarring with a surrounding area of RPE disruption. Scattered areas of vasculitis were noted throughout the periphery (Figure 1B).

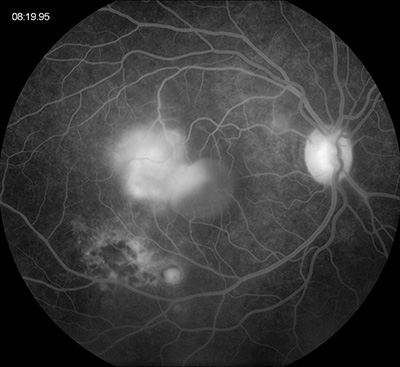

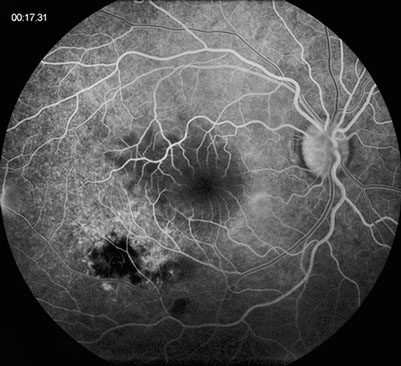

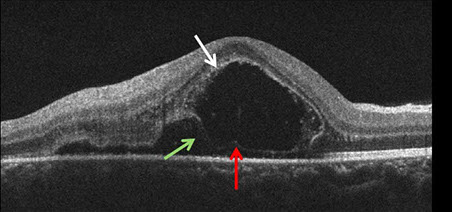

Flourescein angiography demonstrated early blocking in the area of retinitis and retinochoroidal scarring, which progressed to late leakage and staining, respectively (Figure 2). There was a well-circumscribed area of progressive pooling corresponding to the serous detachment space and mild late leakage from the optic disc.

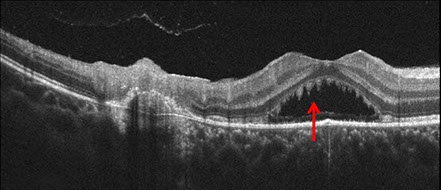

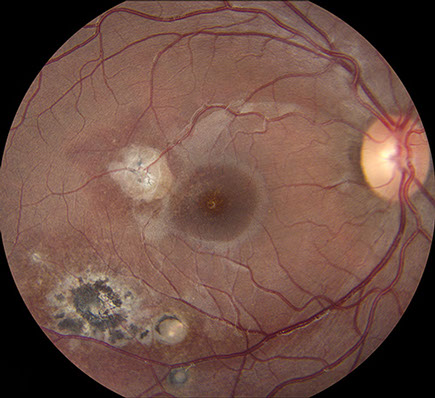

Spectral Domain-Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT) demonstrated subretinal fluid with a band of hyper-reflective material along the superior aspect of the subretinal fluid collection, deep within the outer nuclear layer (ONL) (Figure 3A, white arrow). There was a line of weakly reflective material at the base of the fluid collection that contained punctate foci of hyper-reflectance (Figure 3A, black arrow). Although there was not a definitive detachment of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a distinct hyper-reflective band at the level of Bruch’s membranes was evident. No choroidal thickening or shadowing was present. SD-OCT imaging through the area of retinitis revealed hyper-reflectivity and thickening throughout the retina temporal to the area of serous retinal elevation (Figure 3A). A septum within the subretinal fluid was also noted, as there appeared to be adjacent pockets of fluid, above and below the abnormally thickened inner segment/outer-segment (IS/OS) junction (Figure 3A, red arrow). SD-OCT imaging through the retinochoroidal scar demonstrated areas of irregular thickening of the RPE (black arrow), flanked by RPE atrophy. There was also a bulb-shaped structure that appeared to penetrate through the RPE and Bruch’s membrane (white arrow) and extend into the choroid (Figure 3B).

B

A

Figures 2A and B: Fundus angiography of the right eye. Note areas of early blocking due to old scarring as well as increasing fluorescence of the area of active retinitis. Late pooling of dye in the subretinal space is present (Fig 1B)

B

A

Figures 3: Spectral Domain OCT imaging of the right macula (A) and chorioretinal scar (B). Note the a large collection of subretinal fluid with weakly reflective material at the base (red arrow) and lined superiorly by hyper-reflective material (white arrow). There is a septum within the subretinal fluid (green arrow) with sub-retinal fluid temporally and loculated fluid nasally, containing fibrin like material. There is also active retinitis temporal to this fluid pocket. B. Area of chorioretinal scar demonstrating areas of irregularly and thickened RPE (yellow arrow) flanked by areas of RPE atrophy. There is a bulb-shaped, chorioretinal lesion (white arrow) demonstrating disruption of the RPE and Bruch’s membrane.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis:

The occurrence of a focal retinitis or retinochoroiditis with an adjacent or nearby retinochoroidal scar is highly suggestive of recurrent ocular toxoplasmosis, particularly in a young immigrant girl from Central America. In this particular patient, the size and location of the retinitis suggests a variant of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis known as Punctate Outer Retinal Toxoplasmosis, or PORT, known to occur in about 5% of patients. The differential diagnosis in this patient beyond toxoplasmosis and PORT included sarcoidosis, syphilis, tuberculosis, and Bartonella hensalae-associated retinitis.

Clinical Course:

The clinical appearance was very suggestive in this patient. A diagnosis of recurrent ocular toxoplasmosis was made and she received a 60 day course of 800 mg/160 mg Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim DS) twice daily. No corticosteroids were given. One week after initial presentation, BCVA was 20/160 and there was a decrease in the subretinal fluid collection, and an increase of the size of the yellow-white spots (Figure 4A). The areas of active retinitis and old chorioretinal scarring appeared unchanged. SD-OCT imaging demonstrated persistent subretinal fluid with increased accumulation of material hanging from the undersurface of the retina giving the material a saw-toothed appearance (Figure 4B). One month after initial presentation, BCVA was 20/40 and there was complete resolution of subretinal fluid and no yellow-white spots remained at the level of the deep retina. At 3 months after initial presentation, BCVA was 20/20. The area of retinitis had resolved and there was increased chorioretinal scarring (Figure 5).

B

Figures 4: A. Fundus photograph of the right eye, 1 week later. Note that the consolidation of the area of retinitis and larger yellow-white spots. B. SD-OCT through the area of subretinal fluid showing accumulation of subretinal material in a saw-toothed pattern (red arrow).

A

B

Figures 5: A. Fundus photograph of the right eye 3 months after presentation. Note the well-delineated scarring adjacent to the fovea and early increased pigmentation. B. SC-OCT of the area of new temporal scar. Note the small area of thickened material at the level of the RPE in the area of recent active retinitis.

A

Discussion:

Toxoplasmosis results from infection with the obligate intracellular protozoan parasite Toxoplasmosis gondii.1,2 Although often asymptomatic, infection is frequent worldwide, with an overall seroprevalence of approximately 20% in the United States3,4 and greater than 50% in many endemic regions.1 While congential infections can and do occur via maternal-fetal transmission, most toxoplasmosis is acquired by ingesting contaminated food or water.

Ocular complications of toxoplasmosis have been well described and occur in about 2% of those infected systemically by T. gondii.1,2,5,6 Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis is by far the most common form of ocular involvement, accounting for 30% to 50% of posterior uveitis. In its classic form, toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis presents as an intensely white, focal retinitis with a moderate to severe overlying vitreous inflammation. Adjacent or nearby retinochoroidal scars are common. Other, less frequent forms of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis have also been described, including PORT, focal inner retinitis, and large progressive lesions described in the elderly and patients with HIV/AIDS.2,6 We characterized our patient’s recurrence as PORT, a variant frequently associated with serous retinal detachment and known to constitute approximately 5% of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis.5

The OCT findings of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis have been described by several authors7-10 and include cystoid changes, cystoid macula edema, huge outer retinal cystoid space (HORC), acute thickening and disorganization of the retina, chorioretinal thinning/scarring, posterior vitreous inflammation, epiretinal membrane, and posterior hyaloidal thickening. Our case highlights several novel findings of PORT, including visualization of changes within both the necrotic retinochoroidal lesion and the adjacent subretinal space.11

Take Home Points

- Toxoplasmosis is the most common cause of focal retinochoroiditis

- The occurrence of a focal retinochoroiditis in the setting of an adjacent or nearby retinochoroidal scar is highly suggestive of recurrent toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis

- Punctate Outer Retinal toxoplasmosis (PORT) is a clinically distinct presentation of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis associated with a high rate of serous retinal detachment

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References:

- Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. Part I: epidemiology and course of disease. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 136:973-988.

- Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. Part II: disease manifestations and management. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;137:1-17.

- Jones JL, Kruszon-Moran D, Sanders-Lewis K, Wilson M. Toxoplasma gondii infection in the United States, 1999-2004, decline from the prior decade. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 77(3):405-410.

- Dubey JP, Jones JL. Toxoplasma gondii infection in humans and animals in the United States. Int J Parasitol 2008; 38(11):1257-1278.

- London NJS, Hovakimyan A, Cubillan LDP, Sicerio CD Jr, Cunningham ET Jr. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and causes of vision loss in patients with ocular toxoplasmosis. Eur J Ophthalmol 2011; In press.

- Hovakimyan A, Cunningham ET Jr. Ocular toxoplasmosis 2002;15:327-332.

- 7.Goldenberg D, Goldstein M, Loewenstein A, Habot-Wilner Z. Vitreal, retinal and choroidal findings in active and scarred toxoplasmosis lesions: a prospective study by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013;251(8):2037-2045.

- Oréfice JL, Costa RA, Scott IU, Calucci D, Oréfice F. Spectral optical coherence tomography findings in patients with ocular toxoplasmosis and active satellite lesions (MINAS Report 1). Acta Ophthalmol 2013;91(1):e41-47.

- De Souza EC, Casella AM. Clinical and tomographic features of macula punctate outer retinal toxoplasmosis. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127(10):1390-1394.

- Ouyang Y, Pleyer U, Shao Q, et al. Evaluation of cystoid change phenotypes in ocular toxoplasmosis using optical coherence tomography. PLoS One 2014;9(2):e86626.

- Lujan, BL. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging of punctate outer retinal toxoplasmosis. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2014:28(2);152-156.