West Coast Retina

Case of the Month

September, 2013

Presented by Sara Haug, MD, PhD

58-year-old woman presents with increased floaters and decreased vision bilaterally

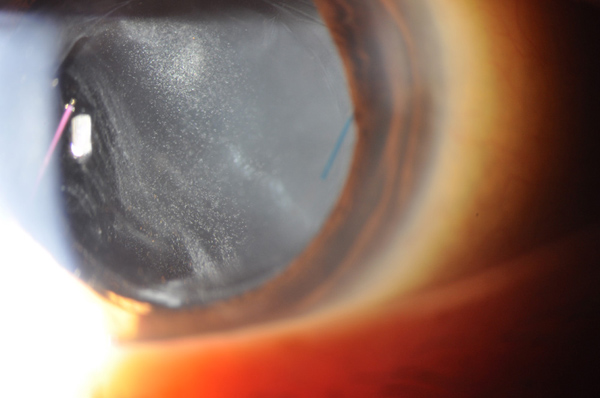

Figure 1: Slit-lamp photograph of the right eye shows a well-centered three-piece intraocular lens and moderately dense chalk-white anterior vitreous cells.

Case History:

A 58-year-old Asian woman presented with a six-month history of blurry vision, increasing floaters, and sensitivity to light in both eyes. She had undergone cataract surgery in both eyes one year earlier and reported increased floaters after the surgery. Her past medical history was notable for hypercholesterolemia. The patient was born and raised in Hong Kong, but had not been outside the United States for many years.

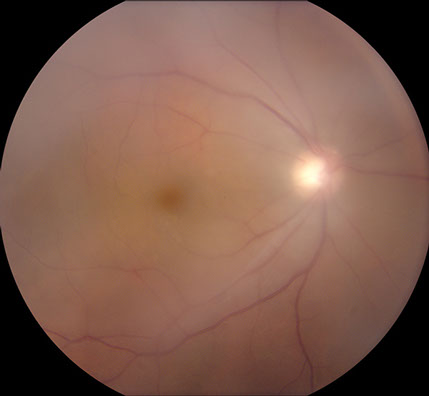

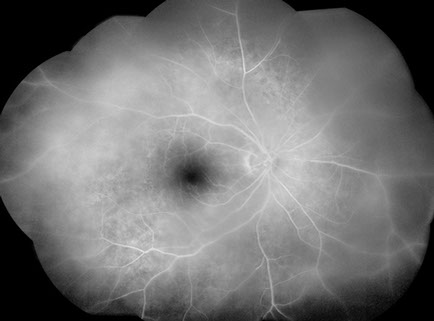

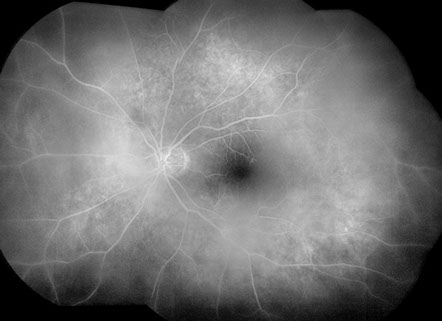

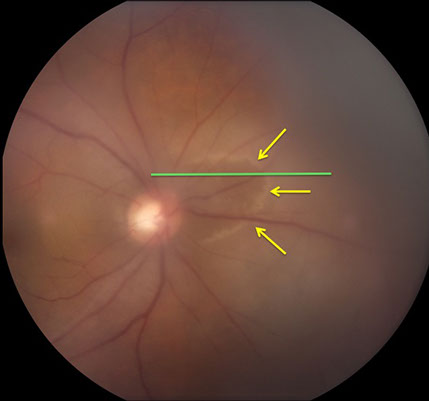

Visual acuity was 20/50 in both eyes and intraocular pressures were 14 mmHg OU. Anterior segment examination showed trace anterior chamber cell and a well-centered 3-piece posterior chamber intraocular lenses OU. Moderately dense anterior vitreous cells were present OU (Figure 1). Posterior segment examination showed moderate haze, worse on the right (Figure 2). The vitreous cells were small, atypically white and often found in clumps throughout the vitreous. A punctate chorioretinal scar was seen superotemporal to the fovea in the left eye (Figure 2B) - otherwise no retinal pathology was noted in either eye. Fluorescein angiography showed no evidence of leakage from the retinal vessels or optic disc in either eye despite the moderately dense vitreous infiltration (Figure 3).

Initial laboratory work-up, chest X-ray, and MRI of the head and orbits were all unremarkable.

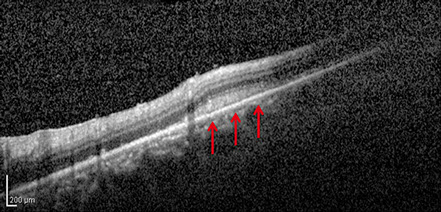

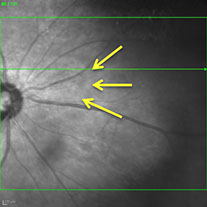

On follow-up visit, a new ring of retinal whitening nasal to the optic disc in the right fundus was noted (Figure 4). SD-OCT imaging through the lesion shows thickening and increased reflectivity of the outer retina (Figure 5).

A

B

Figures 2A and B: Color fundus photographs of the right (A) and left (B) eye show vitreous infiltrates bilaterally. A small chorioretinal scar is seen superotemporal to the fovea on the left (B).

A

B

Figures 3A and B: Fluorescein angiogram montage images of the right (A) and left (B) eye show moderately dense vitritis bilaterally, but no leakage from retinal vessels or the optic disc in either eye. Patchy hyperfluorescence is present bilaterally at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium

A

B

Figures 4A and B: A: Color fundus photograph of the right eye showing a ring of retinal whitening nasal to the optic disc (yellow arrows). Green line is scan line shown in Figure B and area of scan depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5: SD-OCT imaging of the nasal retina of the right eye. The green line on the fundus image (see inset and Fig. 4) indicates the cut of the scan shown. Yellow arrows show the ring of retinal whitening, which corresponds to the area of thickening and increased reflectivity of the outer retina on the SD-OCT image, shown by the red arrows.

What is your Diagnosis?

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of intermediate uveitis is broad and includes sarcoidosis, multiple sclerosis, syphilis, tuberculosis. Less common causes for intermediate uveitis include Whipple’s disease and HTLV-1 associated uveitis. Masquerade syndromes include primary vitreoretinal lymphoma and amyloidosis.

Diagnosis

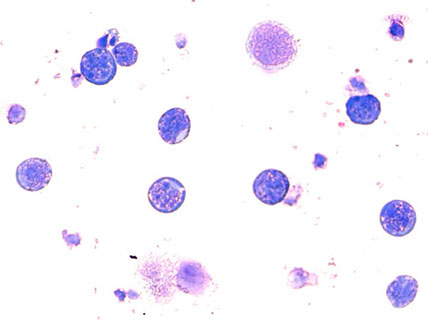

The chalk-white nature of the vitreous infiltration, absence of retinal vascular leakage despite the density of the infiltration, and the development of a curvilinear retinal infiltrate adjacent to the optic disc all raised suspicion of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Diagnostic vitrectomy was performed on the right eye and samples were sent to the National Eye Institute for cytologic analysis. Giemsa stain of the specimen showed small and reactive lymphocytes, macrophages, many degenerative and necrotic cells, and large lymphoma cells with large irregular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and scant basophilic cytoplasm, all supportive of the diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma (Figure 6). IgH gene rearrangement was detected using PCR. Vitreous IL-10/IL-6 was 414pg/ml / 15.6pg/ml ~ 27. Cytologic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma.

Figure 6: Microscopic image of the vitreous samples from the diagnostic vitrectomy performed on the right eye shows large lymphoma cells with large irregular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and scant basophilic cytoplasm, all supportive of the diagnosis of B-cell lymphoma (Giemsa stain).

Discusion

Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma (PVRL) is a rare non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that originally invades the intraocular tissues and is considered a subset of primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL).1,2 The ocular tissues affected by PVRL include the retina, vitreous, and/or optic nerve. PVRL is the most common intraocular lymphoma and is usually classified as a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, although T-cell type has been reported.2 PVRL is distinct from metastatic lymphoma, which often locates to the choroid in patients with known systemic lymphoma, and is quite rare with only 100 - 380 incident cases of PVRL in the US annually.2,3

There is a unique tropism of PVRL for the retina and central nervous system tissues. Of patients diagnosed with PVRL, 65-90% eventually develop primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) and approximately 15-25% of PCNSL patients present with PVRL.2 Given its association with PCNSL, PVRL can be a fatal disease. A study done by Kimura et al in Japan estimates the mean survival rate to be 32 months and 5-year survival rate to be 61%.4

Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma is a masquerade syndrome commonly misdiagnosed as a chronic, posterior uveitis and often initially treated with corticosteroids. Treatment with corticosteroids can suppress the clinical findings and further confound the diagnosis. When there is concern for lymphoma in the eye, the gold standard for diagnosis requires the detection of malignant lymphoid cells from the vitreous, retina, or optic nerve. Routine cytology and histopathology are used to identify the PVRL cells, which are characterized with large irregular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and scanty basophilic cytoplasm (Figure 7).1-3 Molecular analysis of the PVRL cells detects either IgH gene rearrangements in B-cell lymphoma, as in our patient, or T-cell receptor gene rearrangements in T-cell lymphoma.1,2 These studies can be performed at the National Eye Institute.

Treatment for PVRL can include local or systemic therapies. When the CNS is involved, systemic chemotherapy and radiation is the mainstay of treatment. However, in cases such as our patient with a normal MRI of the head and orbits, local therapies may be more appropriate, such as intravitreal chemotherapy or ocular radiation. For example, intravitreal methotrexate has been effective in some case series reports and more recent studies also report efficacy with intravitreal rituximab.2,3

Take Home Points

- Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma can present as intermediate uveitis and should be considered when the findings are atypical, which in our case included chalk-white vitreous cells, a paradoxical absence of retinal leakage on fluorescein angiography despite the presence of dense vitreous cells, and the development of a curvilinear area of outer retinal infiltration.

- Vitreous biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis.

Want to Subscribe to Case of the Month?

References

- Chan, CC, Sen HN. Current concepts in diagnosing and managing primary vitreoretinal (intraocular) lymphoma. Discov Med 2013;81:93-100.

- Chan CC, Rubenstein JL, Coupland SE et al. Primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: a report from an International Primary Central nervous System Lymphoma Collaborative Group symposium. Oncologist 2011;16:1589-99.

- Rajagogap R, Harbour JW. Diagnostic testing and treatment choices in primary vitreoretinal lymphoma. Retina 2011;31:435-40.

- Kimura K, Usui Y, Goto H and the Japanese Intraocular Lymphoma Study Group. Clinical features and diagnostic significance of the intraocular fluid of 217 patients with intraocular lymphoma. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2012;56:383-9