May, 2020

Presented by Michelle Peng, MD

Presented by Michelle Peng, MD

A 36-year-old African American man presented with floaters and blurred vision.

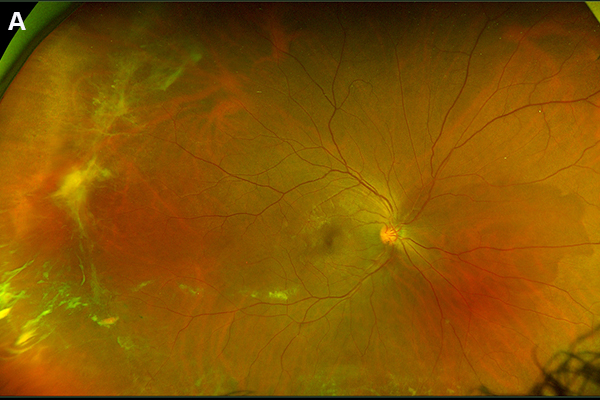

Figure 1A: Wide-field color photo of the right eye. Note the areas of dehemoglobinized vitreous blood and areas of peripheral neovascularization

Figure 1B: Wide-field color photo of the left eye. Note the areas of peripheral neovascularization

Case History

A 36-year-old African American man presented with sudden onset floaters and blurring of his vision in the right eye two weeks prior to appointment.

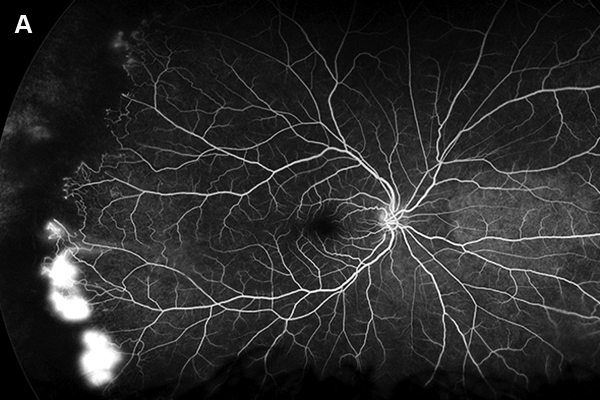

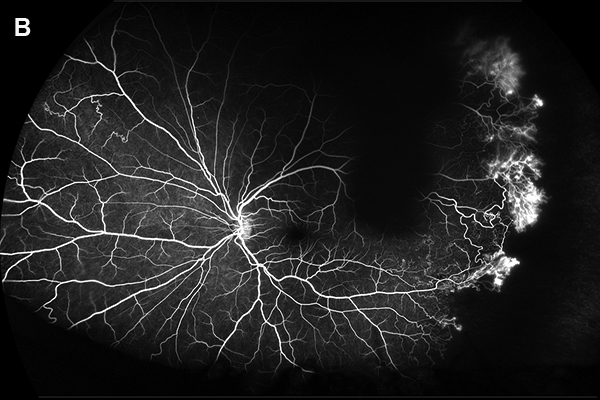

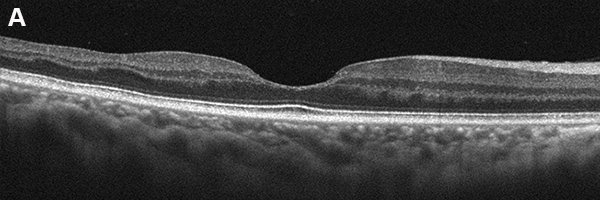

On examination visual acuity was 20/63 in the right eye and 20/32 in the left eye. His pupils were equal, round, and reactive with no afferent pupillary defect. Intraocular pressure and anterior segment examination in both eyes were unremarkable. Fundus examination in the right eye revealed dehemoglobinized vitreous hemorrhage and temporal neovascular fronds with preretinal fibrosis. The left eye had similar temporal findings (Figure 1). Fluorescein angiography highlighted the temporal neovascular sea fan with leakage later in the sequence, and peripheral nonperfusion in both eyes. (Figure 2). Optical coherence tomography demonstrated an epiretinal membrane in the right eye (Figure 3).

Figure 2A: Wide-field fluorescein angiogram of the right eye. Note the peripheral areas of nonperfusion and several areas of neovascularization.

Figure 2B: Wide-field fluorescein angiogram of the left eye. Note the peripheral areas of nonperfusion and several areas of neovascularization. Areas of collateral vessels are seen nasally

Figure 3A: Horizontal SD-OCT scan through the right macula. Note the areas of temporal inner retinal thinning due to prior retinal infarcts. A mild epiretinal membrane is present as well.

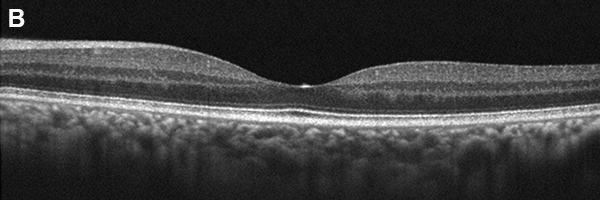

Figure 3B: Horizontal SD-OCT scan through the left macula. The scan is unremarkable.

Differential Diagnosis

Inflammatory conditions: Pars planitis, Panuveitis, Sarcoidosis

Vascular: Diabetes, Branch retinal vein occlusion, Aortic arch syndrome, Carotid cavernous fistula

Inherited conditions: FEVR, Retrolental fibroplasia, Collagen vascular disease)

Hematologic: Leukemia, Sickle cell anemia

Toxic: Talc retinopathy, Radiation retinopathy

Idiopathic: Eale's Disease

Additional History and Diagnosis

Upon further questioning patient had a history of SC sickle cell disease treated with hydroxyurea and folic acid. He had no other medical issues. A diagnosis of sickle cell retinopathy was made and he underwent panretinal photocoagulation to the temporal areas of nonperfusion in the right eye.

Discussion

Sickle cell disease is an inherited hemoglobinopathy with a number of systemic and ocular manifestations. Hemoglobin electrophoresis aids in making the diagnosis. Systemic abnormalities are more prevalent in patients with SS disease and more minimal in those with SC disease. Ocular findings however are more prominent in those with SC disease.1

An occlusive vascular retinopathy can be found in patients with homozygous sickle cell disease, hemoglobin SC disease, sickle cell thalassemia, and hemoglobin SO Arab.2,3 This is characterized by retinal intraretinal and subretinal hemorrhages (salmon patch), neovascularization (sea fan), and circumferential arteriovenous communications at the junction of perfused and nonperfused retina. Salmon patch hemorrhages typically resolve leaving hemosiderin behind or an area of hyperplastic retinal pigmented epithelium/hyperpigmented scar1. Fluorescein angiography can assist in highlighting the junction of perfused and nonperfused retina.

A majority of patients develop peripheral nonperfusion and enlargement of the foveal avascular zone. Visual prognosis is generally good with fewer than 10% of patients with SC and SS disease developing visual loss.4 When vision loss dose occur it is most often in the setting of vitreous hemorrhage from neovascularization. Loss of vision may also occur due to paracentral occlusive vascular changes,4 central retinal artery occlusion,5 central retinal vein occlusion,1 macular hole,6 choroidal infarct, ischemic optic neuropathy,7 neovascular glaucoma,8 and proliferative retinopathy resulting in the extension of subretinal or preretinal bleeding, or combined tractional-rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Angioid streaks in these patients are rarely associated with choroidal neovascularization.

Spontaneous regression or autoinfarction of areas of neovascularization may occur in proliferative sickle cell retinopathy, thus treatment is probably unnecessary unless the patient develops vitreous hemorrhage.2,4 Photocoagulation or cryotherapy to areas of neovascularization or scatter laser to vascular nonperfusion can assist in vascular regression.9,10 Choroidal neovascularization, ischemia, and retinal holes may develop post treatment.11-13 Surgery may be performed in cases of retinal detachment.14