November, 2022

Presented by Georgia Kamboj, MD, PhD

Presented by Georgia Kamboj, MD, PhD

A 16-year-old Asian male presents with bilateral night blindness and poor central vision.

Figure 1A: Color photo of the right eye. Note pigmentary changes, submacular fibrosis, and visible choroidal vessels.

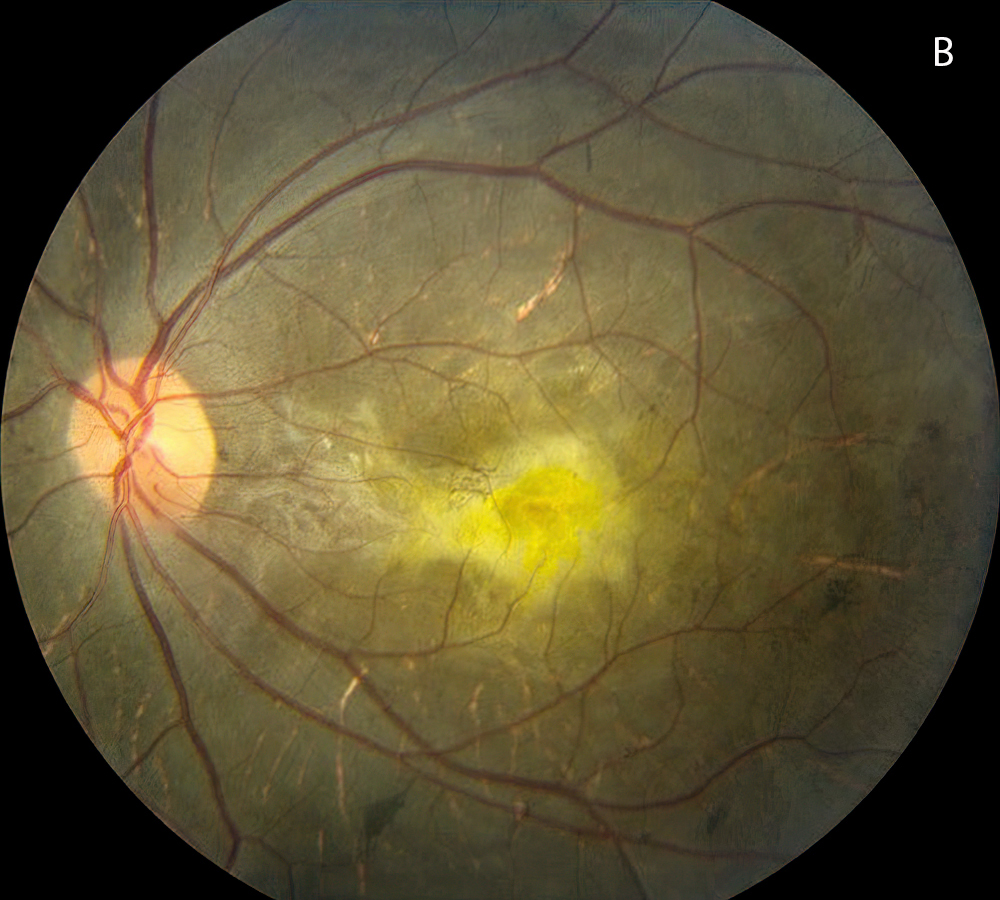

Figure 1B: Color photo of the left eye. Note similar findings as seen in the right eye with pigmentary changes, submacular fibrosis, and visible choroidal vessels.

The patient noted progressive night blindness and vision loss since age 8. He denied flashes/floaters, metamorphopsia, and photophobia. His past ocular history was otherwise unremarkable. He was an only child, and of Chinese heritage. There was no family history of consanguinity or night blindness.

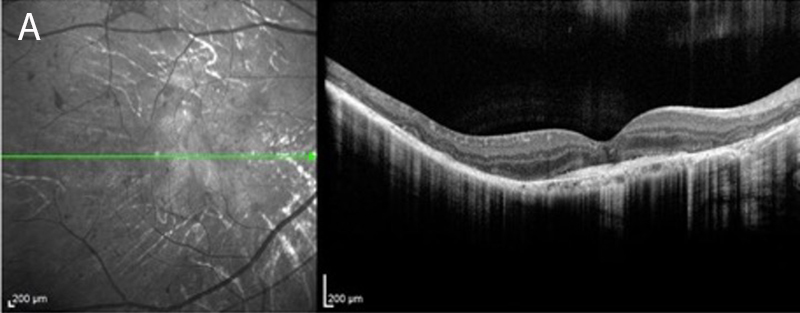

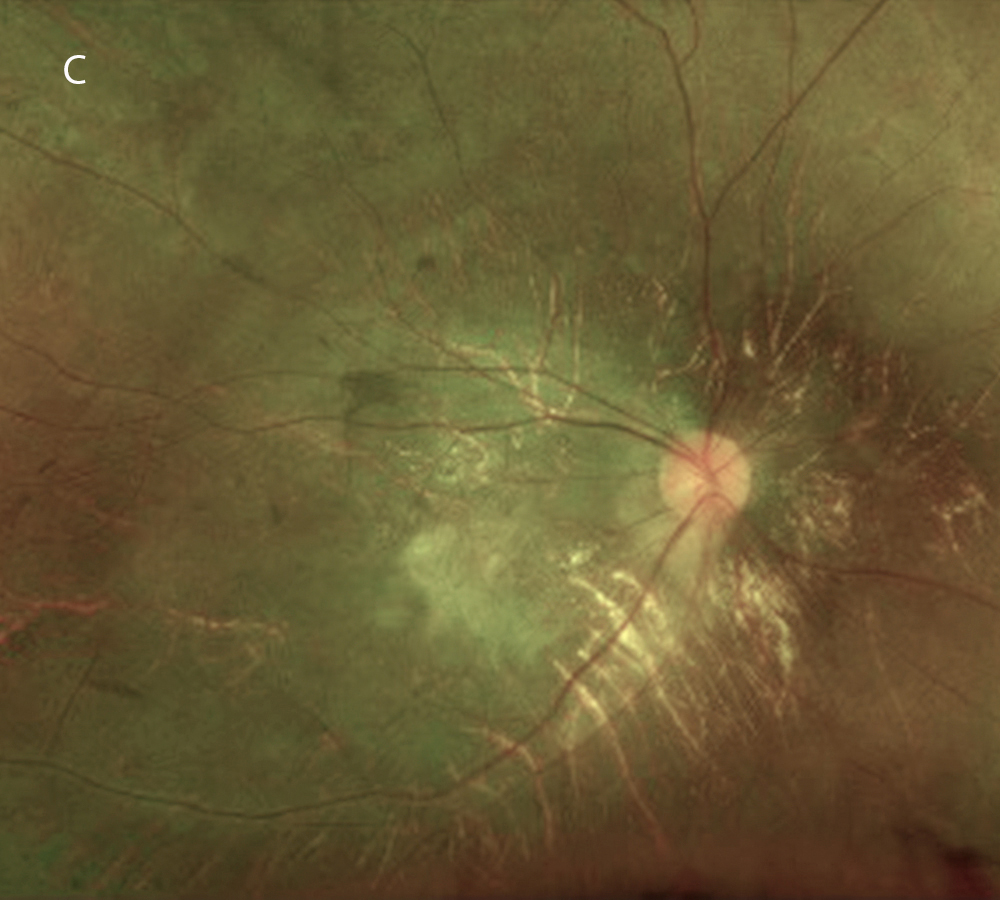

The patient’s best corrected Snellen visual acuity measured 5/200 in the right eye (OD) and 20/250 in the left eye (OS). Intraocular pressure was normal in both eyes. Anterior segment exam of the right and left eyes was unremarkable. Posterior segment exam was significant for bilateral pigmentary retinopathy, visible choroidal vessels and yellow submacular fibrosis (Figures 1A and B). There were bone spicules and pigment clumping in the retinal periphery of both eyes. OCT imaging showed diffuse outer retinal atrophy and submacular fibrosis (Figures 2A and B).

Figure 2A:OCT-SD scan of the right macula. Diffuse outer retinal atrophy is present with subretinal fibrosis

Figure 2B:OCT-SD scan of the left macula. Diffuse outer retinal atrophy is present with subretinal fibrosis

Past medical history was significant for pan-hypopituitarism, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, undescended testis, obesity and short stature. He had a wide-based gate with otherwise normal cerebellar testing. MRI of his brain was notable for mild vermis hypoplasia, but without a “molar tooth sign” on axial images. He had near normal mentation.

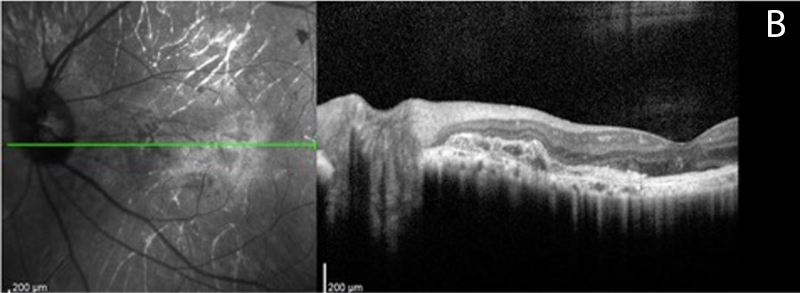

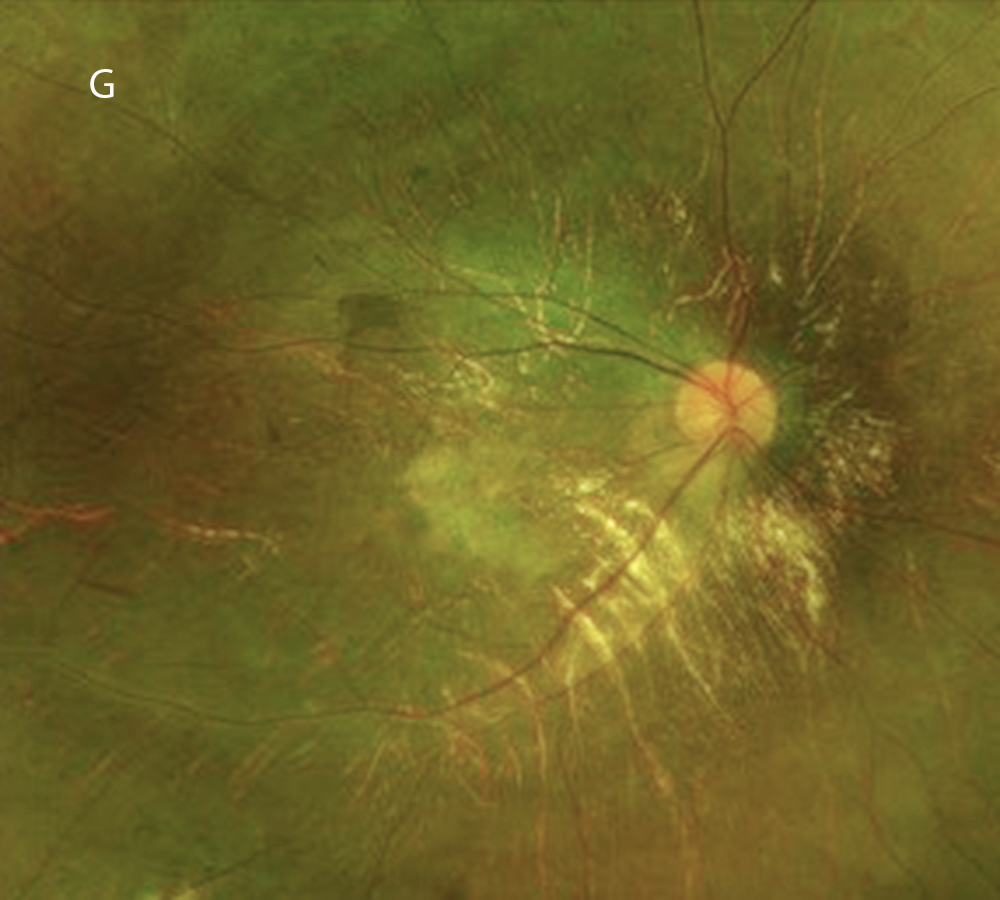

Patient CourseOver the course of 8 years of follow-up there was a progressive increase in the visibility of the choroidal vessels and extension of the submacular fibrotic area (Figures 3A-H). Fundus autofluorescence at age 23 was remarkable for generalized hypo-autofluorescence except for small slivers of preserved RPE (Figure 4).

Figure 3A: Color photo of the right eye at presentation, age 16. Note pigmentary changes, submacular fibrosis, and visible choroidal vessels.

Figure 3B: Color photo of the left eye at presentation, age 16. Note pigmentary changes, submacular fibrosis, and visible choroidal vessels.

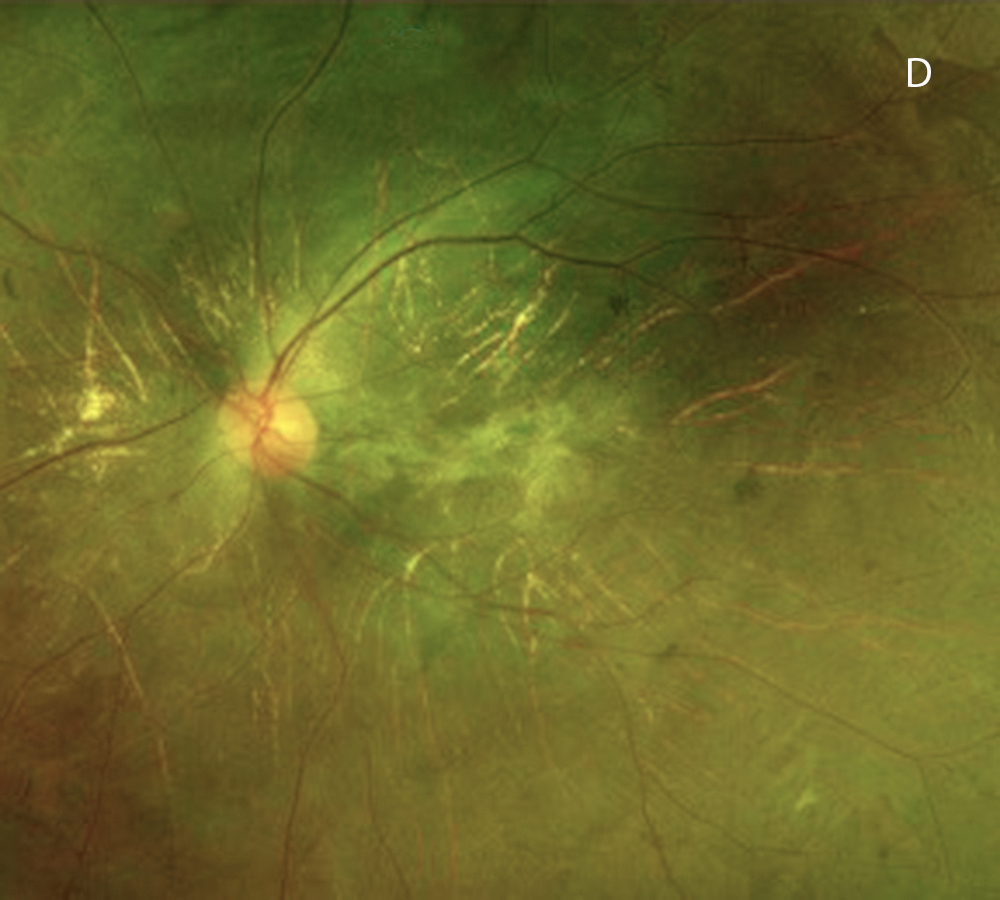

Figure 3C: Color photo of the right eye 6 years later, age 22. Note the greater visility of the choroidal vessels.

Figure 3D: Color photo of the left eye 6 years later, age 22. Note the greater visility of the choroidal vessels.

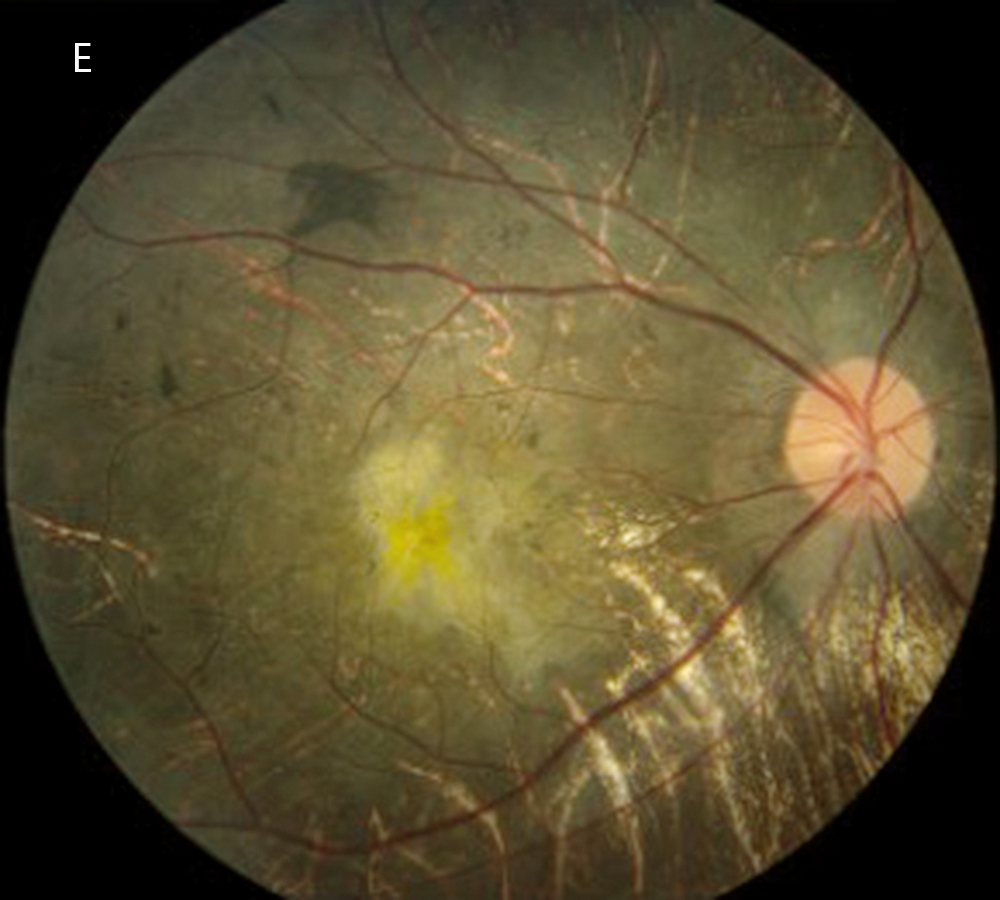

Figure 3E: Color photo of the right eye 7 years after presentation, age 23. Note the progressive greater visility of the choroidal vessels.

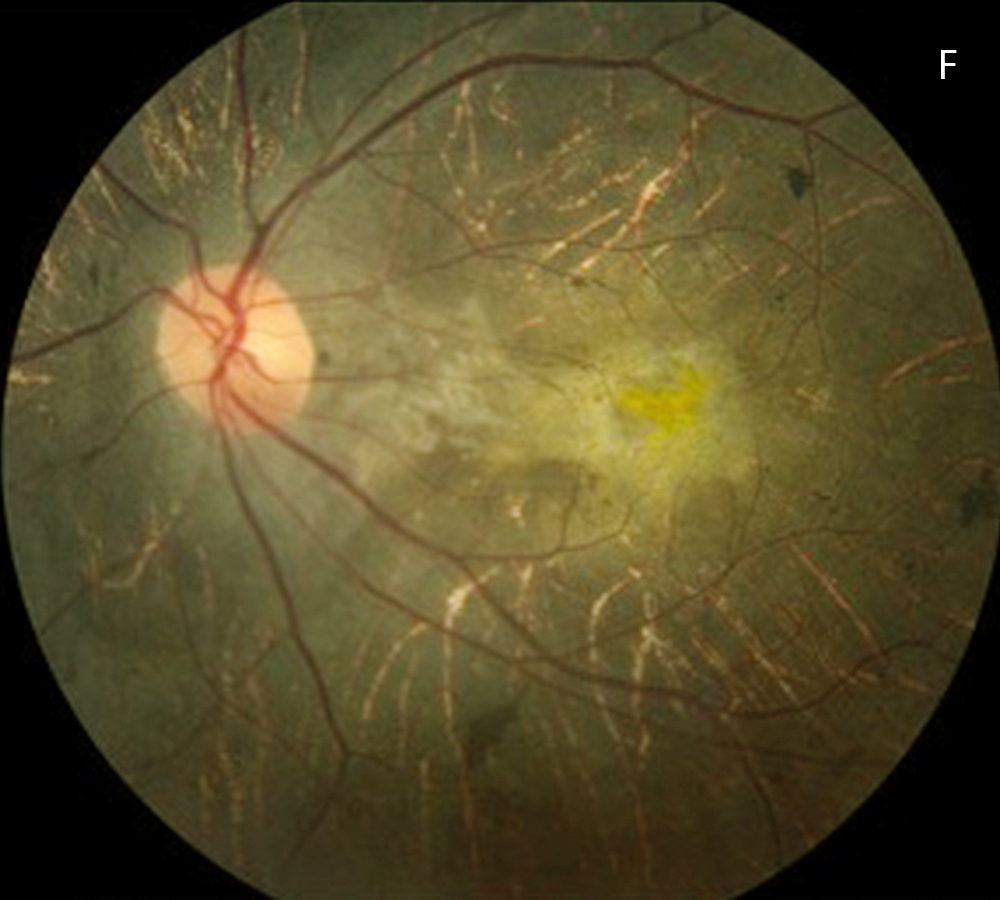

Figure 3F: Color photo of the left eye 7 years after presentation, age 23. Note the progressive greater visility of the choroidal vessels.

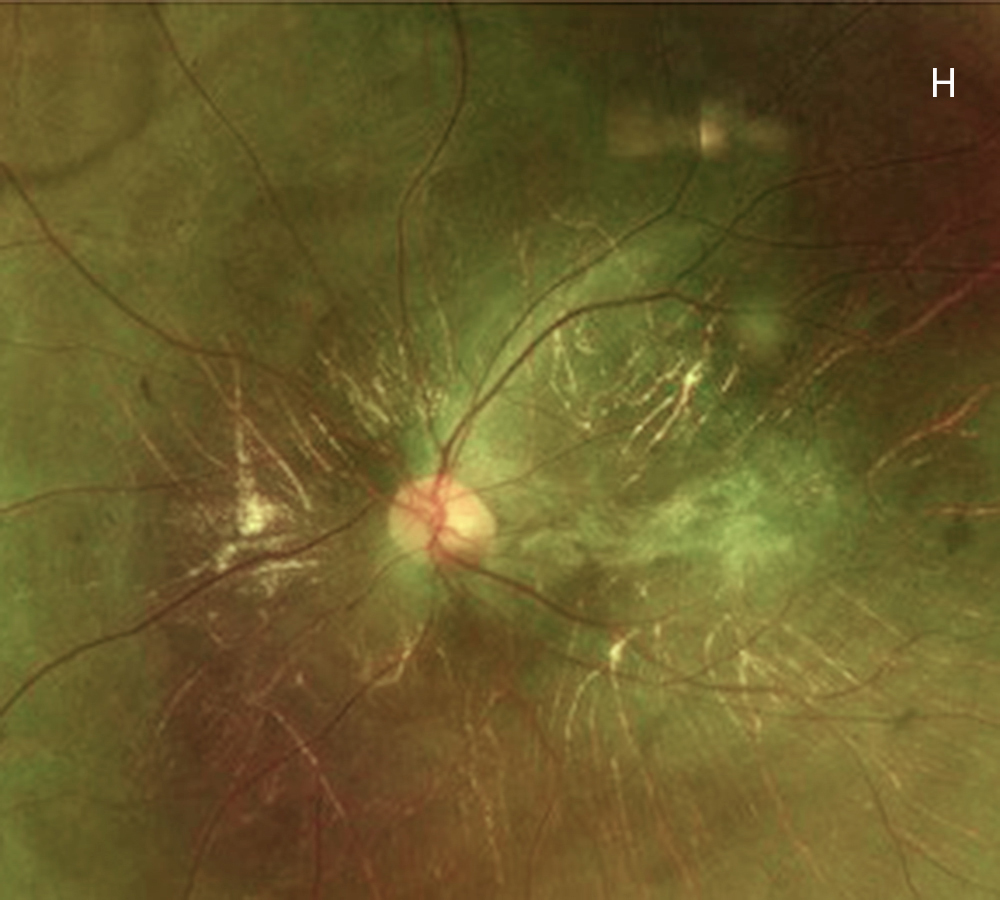

Figure 3G: Color photo of the right eye 8 years after presentation, age 24. Note further progression.

Figure 3H: Color photo of the left eye 8 years after presentation, age 24. Note further progression.

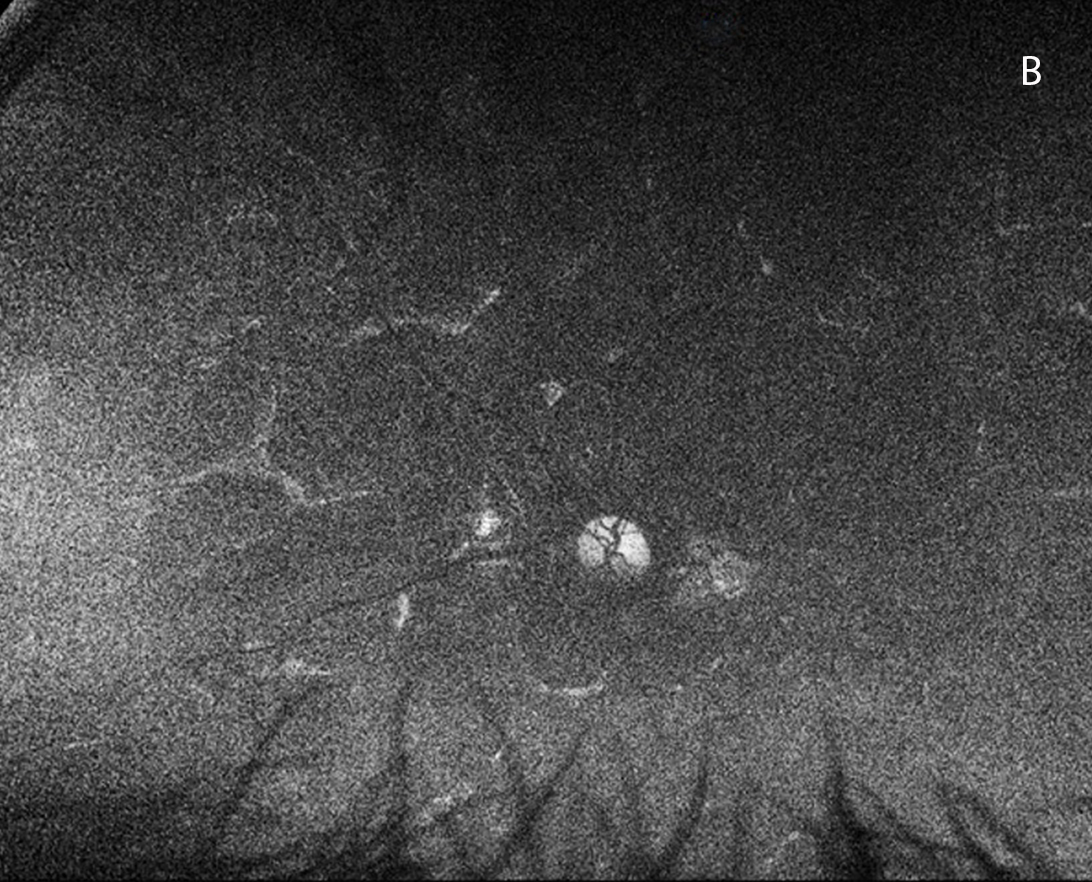

Figure 4A: Fundus autofluorescence of the right eye, age 24. Widespread hypo-autofluorescence is seen with only small islands of preserved RPE.

Figure 4B: Fundus autofluorescence of the left eye, age 24. Widespread hypo-autofluorescence is seen with only small islands of preserved RPE.

Differential Diagnosis

This patient had findings suggestive of a chorioretinal dystrophy with submacular fibrosis and prominent choroidal vessels. Genetic testing was performed and revealed two heterozygous variants within the PNPLA6 gene (2986A>G and 3200C>T). Based on the patient’s systemic manifestations, clinical features and genetic findings, we determined that the most likely diagnosis was Boucher-Neuhauser Syndrome (BNS) due to compound heterozygosity of 2 pathogenic PNPLA6 variants.

DiscussionPatatin-like phospholipase domain containing 6 (PNPLA6) encodes neurogenic target esterase which plays an important role in stabilisation of the plasma membrane in the nervous system, including that of photoreceptor inner segments.1

PNPLA6-related disorders have variable clinical phenotypes characterized by combinations of cerebellar ataxia, chorioretinal dystrophy, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, peripheral neuropathy, hair anomalies, short stature, and intellectual disability.2 Chorioretinal dystrophy is a feature of three of the PNPLA6 syndromes: Boucher-Neuhauser Syndrome, Oliver-McFarlane Syndrome and Laurence-Moon Syndrome. Our patient showed no signs of childhood-onset ataxia, peripheral neuropathy, or spastic paraplegia (which are present in Laurence-Moon Syndrome) and he did not have trichomegaly (a characteristic feature of Oliver-McFarlane Syndrome). Boucher-Neuhauser Syndrome was therefore the most likely diagnosis given our patients systemic, ocular and genetic findings. Of note, ataxia is considered one of the key features of Boucher-Neuhauser Syndrome, however there are reports of patients with this syndrome who do not develop ataxia until later in life (after age 50).3

To date, there are 83 reported pathogenic variants of the PNPLA6 gene.3 One variant (2986A>G) found in our patient has been previously reported in a patient with Boucher-Neuhauser Syndrome.3 The second variant (3200C>T) has been reported previously in a patient with Autosomal Recessive Hereditory Spastic Paraplegia as part of a compound heterozygous recessive mutation.4 Hereditory Spastic Paraplegia has characteristic systemic and ocular abnormalities that differ from those seen in our case.4

The retinal appearance of PNPLA6-related disorders can be diverse, with the full spectrum ranging from a mild retinal pigment epitheliopathy to severe chorioretinal atrophy.2 In addition, nyctalopia and chorioretinal abnormalities can precede systemic signs and symptoms.3 Choroideremia-like retinal changes therefore warrant early genetic testing.