October, 2022

Presented by Malini Veerappan Pasricha, MD

Presented by Malini Veerappan Pasricha, MD

An 86-year-old Caucasian man presented with a hyphema in the right eye.

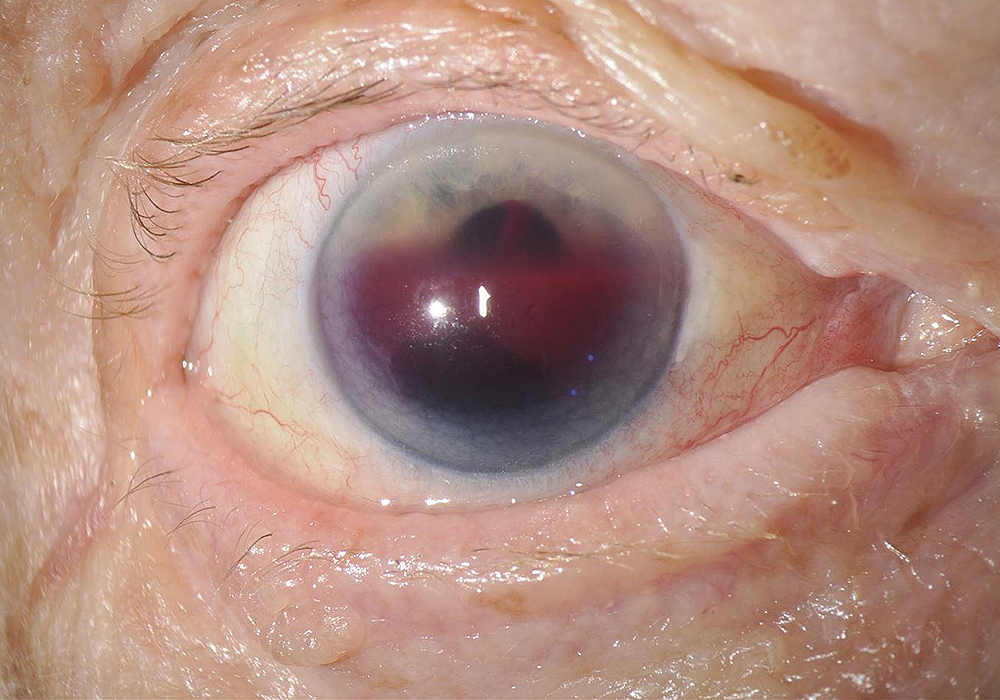

Figure 1:Anterior segment photo of the right eye. Note the 60-70% hyphema, without obvious ocular inflammation.

The patient noticed progressive blurring of vision in the right eye for one day. He reported similar episodes of blurring in this eye 4-5 times in the last few years. He denied pain, preceding flashes or floaters, headaches, and metamorphopsia. No history of ocular trauma. His past ocular history was significant for posterior vitreous detachment and epiretinal membrane OU. His past medical history was significant for atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. His medications include apixaban, carvedilol, and lovastatin. Family history was significant for cancer, systemic hypertension, and type 2 diabetes. He was a cigar smoker. Review of systems was negative.

The patient’s best corrected visual acuity measured HM OD and 20/32 OS. Intraocular pressure was 36 mmHg OD and 20 mmHg OS. The left eye examination was significant for a nuclear sclerotic cataract and pseudoexfoliative material on the anterior capsule. Anterior segment examination of the right eye was notable for a 60-70% hyphema (Figure 1). There was no obvious signs of inflammation. The posterior examination of the right eye showed a dense vitreous hemorrhage. On B-scan ultrasonography, there was no evidence of retinal detachment or choroidal tumor.

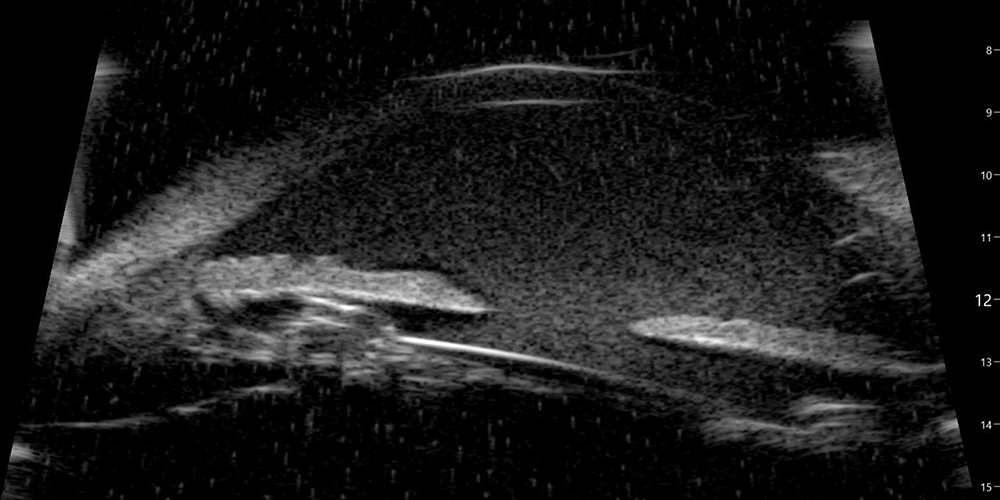

Figure 2:Ultrasound scan of the anterior segment. Note the hyphema and the haptic contact with the posterior iris surface.

Differential Diagnosis

Trauma

Nontraumatic Etiologies

Additional History and Patient Course

Undilated examination of the right eye revealed a temporal circumlinear iris transillumination defect. Review of prior operative note indicated that the cataract surgery was challenging due to poor dilation (warranting malyugin ring placement) and zonular instability (presumably due to pseudoexfoliation sydrome). A one-piece IOL was noted to be placed in the capsular bag. An ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) was performed and revealed haptic-iris touch (Figure 2). A diagnosis of uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome was made and the patient was scheduled for lens exchange surgery.

Discussion

Blunt trauma is the most common cause of a hyphema. Compressive force to the globe can cause injury to the iris, ciliary body, trabecular meshwork and associated vasculature.1,2 However, in our case, there was no history of trauma. Non-traumatic causes of hyphema can be divided into post-surgical, ischemic, neoplastic, inflammatory/infectious, and vascular categories (see differential diagnosis above).2,3 A thorough history, imaging, and systemic workup is necessary to determine the diagnosis, especially when clinical examination is limited due to blood in the anterior chamber.

UGH syndrome, or Ellingson syndrome, is a rare complication caused by mechanical chafing of the IOL on the angle of the anterior chamber, the iris, and/or the ciliary body.4,5 The uveitis is primarily due to mechanical disruption of blood aqueous barrier.4,5 The increased intraocular pressure may be caused by a variety of factors, including pigment dispersion, uveitis, clogging of red blood cells in the angle, direct damage to the angle, or even a steroid response from topical steroids used to treat the syndrome.4,5 With the evolution of lens manufacturing and surgical techniques, the incidence of UGH syndrome has declined over the last three decades, from approximately 3% to 1.2% per year.4

Originally described by FT Ellingson in 1978, UGH syndrome was discovered to be a complication of Choyce Mark rigid anterior chamber closed loop lenses.6 More recent data has shown that UGH syndrome can result from any IOL implant in the anterior or posterior chamber.7-10 Lenses with imperfect construction, imperfect positioning, or improper sizing are the primary risk factors.4 Imperfect construction includes warped footplate edges or sharp edges due to substandard polishing by the manufacturer, or antiquated loop design (planar design poses higher risk than angulated).4 Imperfect positioning classically refers to placement of a single-piece IOL in the sulcus. However, more evidence has suggested that even lenses placed in the capsular bag can lead to signs of UGH, especially in patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome (phacodonesis due to zonular laxity results in chafing of the posterior iris surface and focal capsular fibrosis around the haptic causing iris touch), plateau iris syndrome (anterior rotation of ciliary processes), intensive facedown position (for example, in yoga, causing pseudophacodonesis),11 and/or a large capsulorrhexis during surgery12 (increasing risk of movement of IOL out of the bag).4 Another example of imperfect positioning is an upside-down 3-piece IOL (causing anterior instead of the conventional posterior vaulting).4 Improper sizing includes anterior chamber IOLs that are either too small (causing excessive intraocular movement) or too big (causing trauma to the angle and its vasculature).4 More recently, other surgical devices such as capsular tension rings,4 cosmetic iris implants,13 and glaucoma filtration devices (eg iStent, Hydrus microstent, Ahmed tube, Express shunt)14-17 have been implicated as sources of UGH syndrome. Reports of late-onset UGH have been noted in eyes with Soemmering rings, causing anterior shift of IOLs leading to iris-haptic touch.18

UGH syndrome can develop immediately after the inciting surgery, or years later.4 It may present with transient blurring of vision, or a gradual diminution. Patients may also describe episodic or constant symptoms of photophobia, pain, erythropsia, and eye redness.4 Clinical examination can show a spectrum of iris transillumination defects, pigmentary dispersion in the anterior chamber, pigment deposits on the corneal endothelium and IOL, anterior chamber hemorrhage ranging from dispersed red blood cells to microhyphemas to hyphemas, and elevated intraocular pressure.4 Secondary consequences include iris neovascularization, cystoid macular edema, corneal edema, vitreous hemorrhage (due to communication between anterior and posterior segments from a posterior capsular rent or disruption of the anterior hyaloid face),19 and glaucomatous optic nerve atrophy.4 Gonioscopy can aid in visualizing blood in and erosion of the anterior chamber angle.4 UBM is a reliable tool for diagnosis of UGH syndrome, as it helps determine the position of the optic and haptics in relation to their surrounding ocular structures.20 Anterior segment optical coherence tomography is a good alternative imaging tool.21

Management of UGH syndrome includes medical and surgical options. The IOP should be controlled with topical and systemic medications. Unfortunately, the elevated IOP can become a chronic issue leading to progressive glaucomatous optic nerve damage.22 Topical steroids should be used to control anterior segment inflammation. Cycloplegics are also helpful to relieve ciliary and iris sphincter spasms. Miotics should be avoided as they increase mechanical chaffing of the iris.4 Specific treatment may be offered to patients where the cause is localized. For example, laser peripheral iridotomy may help patients with reverse pupillary block (posterior bowing of iris), which is most seen in myopic or vitrectomized eyes with a sulcus IOL.23 Laser irido- or trabeculoplasty may be helpful in patients with minimally invasive glaucoma devices causing UGH.4 Rarely, if an iris blood vessel is found to be the causative source, an Nd YAG laser can be used to coagulate the bleed.4 In cases where medical therapy fails or more definitive treatment is desired due to frequent recurrence of symptoms, surgical removal of the causative implant is warranted. In the case of IOL implants, surgeons should consider exchange, explant, repositioning, or amputation of a haptic.24 Approximately 12% of IOL exchange surgeries are attributed to UGH syndrome.7,8