September, 2022

Presented by Georgia Kamboj, MD, PhD

Presented by Georgia Kamboj, MD, PhD

A 73-year-old white man presents with sudden onset blurred vision in the right eye.

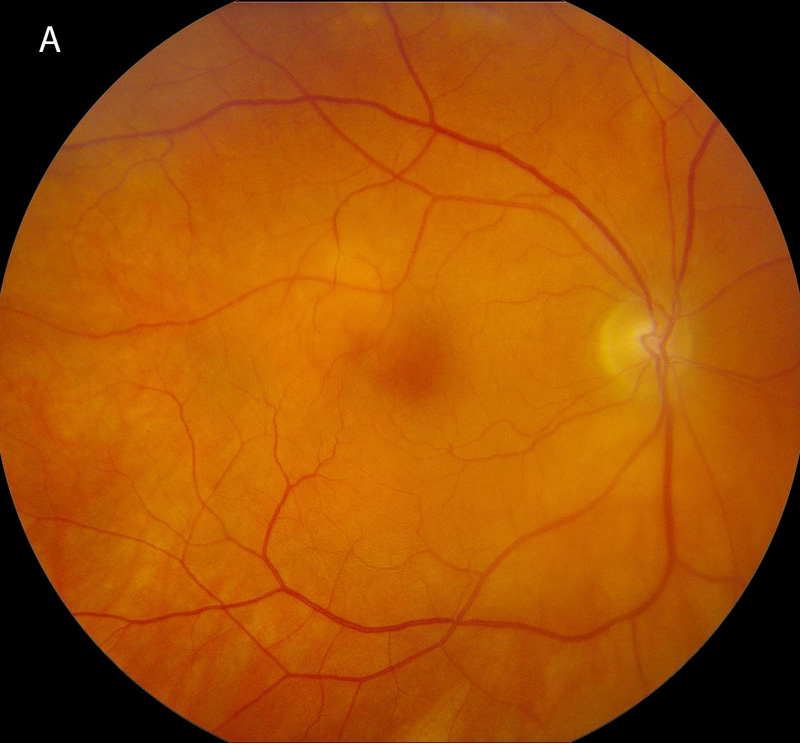

Figure 1A: Color photo of the right eye. Note the area of retinal whitening superotemporal to the fovea.

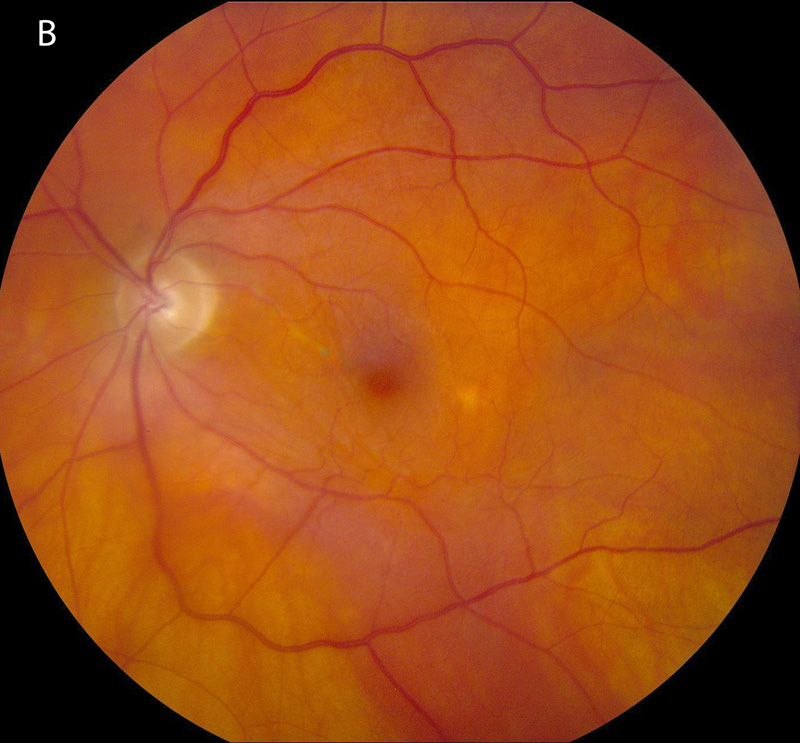

Figure 1B: Color photo of the left eye. A mild epiretinal membrane is present and mild RPE changes from a prior retinal detachment.

The patient noted blurred central vision in the right eye 2 days prior to presentation. He denied flashes/floaters, metamorphopsia, and photophobia. His past ocular history was significant for pseudophakia complicated by haemorrhagic choroidal detachment in the right eye 6 years prior, left retinal detachment treated with pneumatic retinopexy and an epiretinal membrane in the left eye. Past medical history was significant for polymyalgia rheumatica for which he was taking 1 mg of oral prednisone daily, ulcerative colitis, hypertension, COPD and atrial fibrillation. Family history is noncontributory. Review of systems was negative.

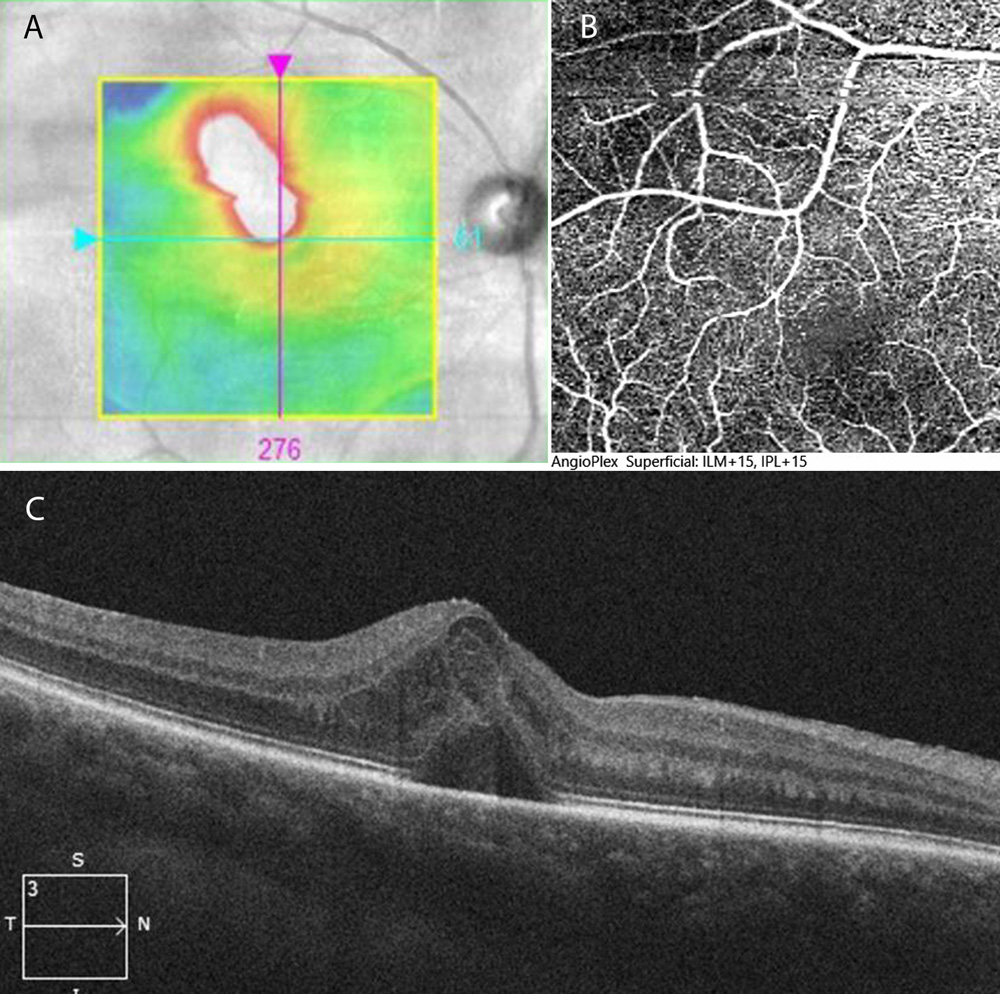

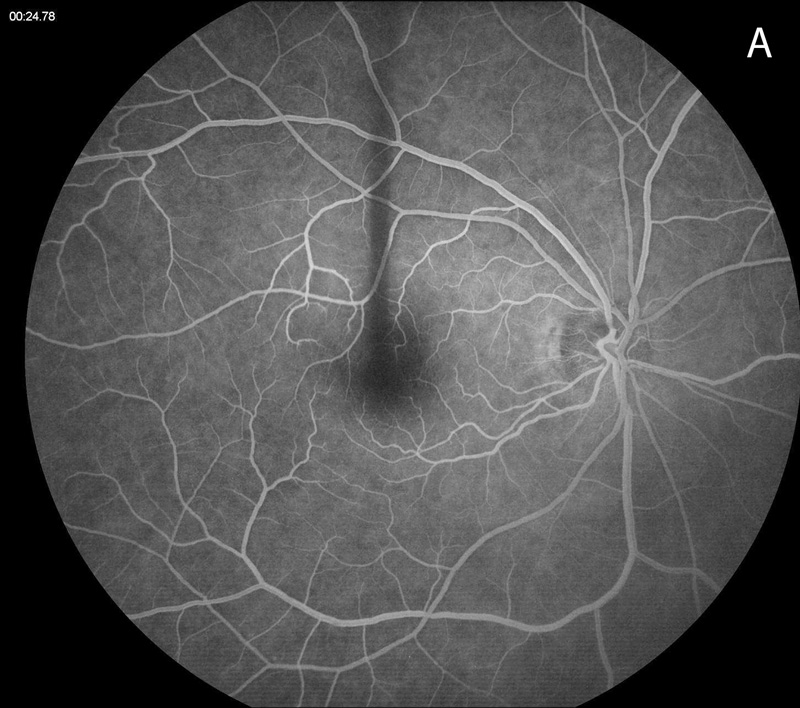

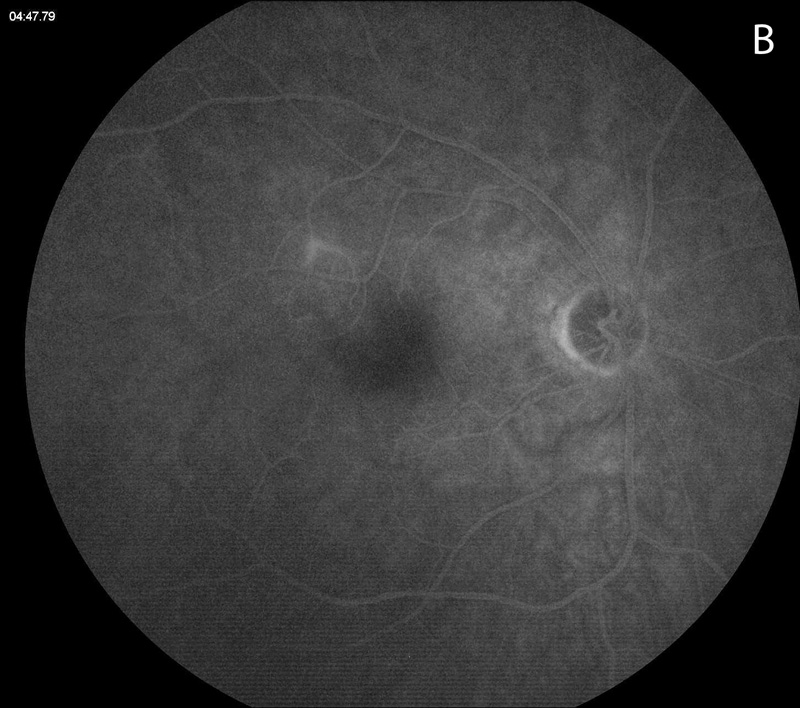

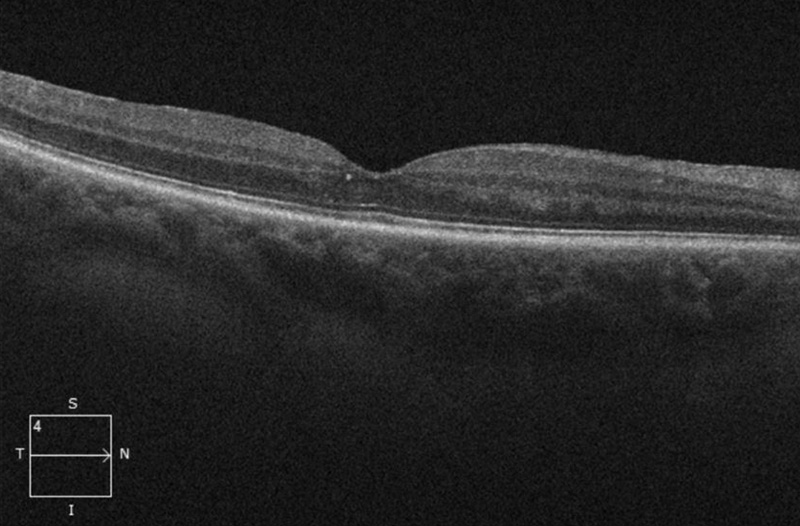

On examination, the patient’s best corrected Snellen visual acuity measured 20/80 in the right eye (OD) and 20/63 in the left eye (OS). Intraocular pressure was normal in both eyes. Anterior segment exam of the right and left eyes revealed posterior chamber intraocular lenses in both eyes, a temporal iridectomy in the right eye and corneal edema in the right eye. No anterior chamber or vitreous cells were noted. Posterior segment exam of the right eye was significant for a small area of retinal whitening and edema superotemporal to the fovea (Figure 1A). The left fundus was notable for an epiretinal membrane, a pigmented demarcation line through the macular from prior retinal detachment and a retinal break with surrounding cryotherapy scars in the superotemporal periphery (Figure 1B). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the right eye showed cystoid macular edema (Figure 2A and C). OCT angiography showed no vascular occlusion (Figure 2B). OCT of the left eye showed an epiretinal membrane. Fluorescein angiography (FA) of the right eye showed a focal area of perivenous hyperfluorescence consistent with vascular leakage (Figure 3). The left eye FA was unremarkable.

Figure 2A-C: OCT-SD and angiogram of the right macula. Note the area of retinal thickening due to edema superotemporal to the fovea (Figure 2A and C). The OCT angiogram shows complete filling of the retinal vessels in the macula (Figure 2C).

Figure 3A: Fluorescein angiogram of the right macula. The early arteriovenous phase shows normal filling of the retinal vessels.

Figure 3B: Fluorescein angiogram of the right macula. Note the fluorescein staining of the superotemporal branch vein.

Differential Diagnosis

Additional History and Work-Up

Workup for infectious and autoimmune causes of vasculitis including testing for tuberculosis, syphilis, toxoplasma and bartonella were negative. Inflammatory markers were within normal limits. CBC showed mild anemia and normal platelet count.

Diagnosis and Patient Course

A diagnosis of occlusive vasculitis in this patient with ulcerative colitis was suspected. The retinal whitening was interpreted to be due to the focal vasculitis in the small macular branch vein. Staining and leakage was noted on fluorescein angiography with cystoid macular edema. The patient was treated with a posterior subtenons triamcinolone injection. Resolution of cystoid macular edema was noted 3 weeks later and there was no recurrence at 2 months post treatment (Figure 4). Visual acuity improved to 20/20 at 2 months post treatment.

Figure 4: OCT-SD of the right macula 2 months following a periocular triamcinolone injection. The macular edema has resolved. Trace intraretinal lipid is present (intraretinal hyperreflective material).

Discussion

Branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) is common, with an incidence of approximately 0.5%.1 Risk factors for BRVO include age, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ocular hypertension, and glaucoma.2 After adjusting for age and hypertension status, the Beaver Dam Eye Study showed that arteriovenous nicking and focal arteriolar narrowing are independent risk factors for BRVO.3

Age and hypertension may have contributed to the development of BRVO in the case presented here, however there are also some unusual features that suggest an underlying inflammatory cause. Firstly, arteriovenous nicking and focal arteriolar narrowing are not prominent features. In addition, the site of venous occlusion did not correspond to an area of arteriolar crossing which is expected when BRVO is due to arteriosclerotic changes. The fluorescein angiogram shows perivenular leakage of the culprit vessel which is uncharacteristic of BRVO without associated vasculitis.

Occlusive retinal vasculitis has a wide range of etiologies.4 Infectious causes can be bacterial (tuberculosis, Whipple’s disease, Bartonella), viral (CMV, HSV, VZV, EBV, HTLV-1, Dengue fever), or parasitic (Rickettsia, Toxplasma gondii). Non-infectious causes include intravitreal medications such as vancomycin or brolucizumab (secondary to a type IV hypersensitivity reaction), and systemic diseases such as Behcet’s, sarcoidosis, ANCA associated vasculitis, SLE, systemic sclerosis, Susac syndrome, multiple sclerosis, primary vitreoretinal lymphoma, amyloidosis and inflammatory bowel disease. Rarely BRVO can be caused by genetic mutations (Autosomal dominant neovascular inflammatory vitreoretinopathy (ADNIV)) or can be idiopathic (idiopathic retinal vasculitis, aneurysms, and neuroretinitis (IRVAN)). Ulcerative colitis has specifically been linked to central retinal vein occlusion, BRVO and cilioretinal artery occlusion in a handful of case reports.5-7 There does not seem to be a correlation between retinal vascular events and intestinal disease activity or duration in reported cases.

Treatment of occlusive vasculitis involves a combination of management of the underlying systemic disease, and local management of macular edema or neovascular complications.4 Corticosteroids, either systemic or local can be used after ruling out infectious causes. In some cases, and depending on the underlying disease process, immunomodulatory medications may be necessary.4