October, 2021

Presented by Presented by Malini Veerappan Pasricha, MD

Presented by Presented by Malini Veerappan Pasricha, MD

A 48-year-old Caucasian man from San Francisco, CA presented with progressive blurring of the inferior visual field in his right eye.

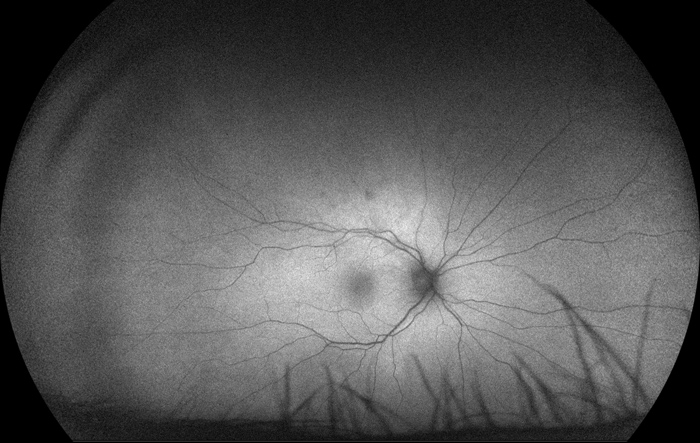

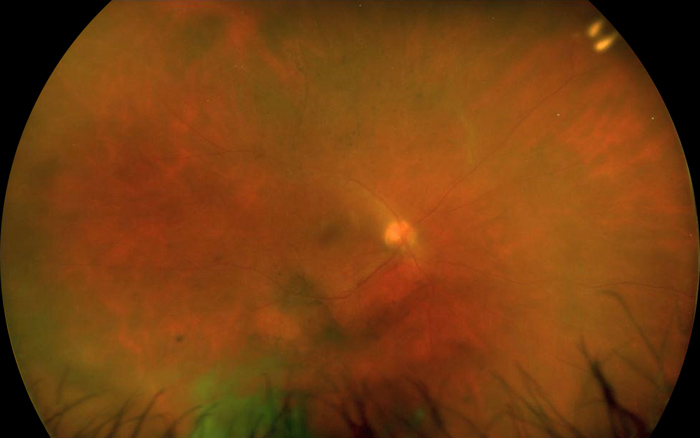

Figure 1:Widefield photograph of the right eye. Note the wedge-shaped region of retinitis superiorly, with a diaphanous leading edge extending down to the superior arcade.

The patient first noticed a “smudge” in the inferior portion of his right eye vision one and a half weeks prior to presentation, which gradually enlarged. Two days prior to presentation, he experienced worsening pain, redness, and photophobia of his right eye. He denied any flashes, floaters, metamorphopsia, or headaches. His past ocular history was otherwise unremarkable. Family history was significant for cancer, systemic hypertension, and type 2 diabetes. He was a former smoker, and denied use of illicit substances. Review of systems was positive for a skin rash on his back and genitalia, on and off over the past two years.

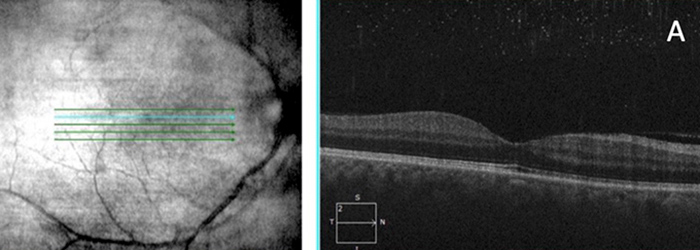

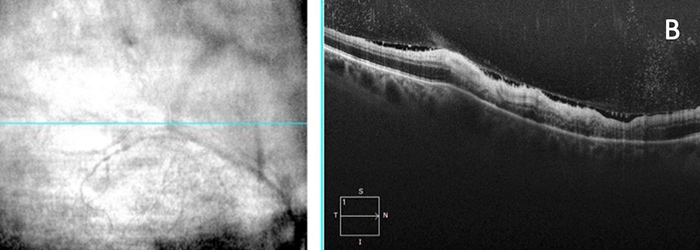

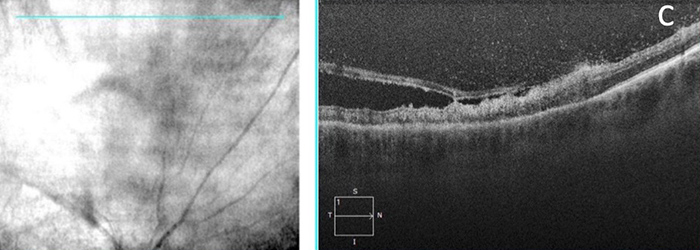

The patient’s best corrected Snellen visual acuity measured 20/63 in the right eye (OD) and 20/25 in the left eye (OS). Intraocular pressure was 6 mmHg OD and 11 mmHg OS. The left eye examination and imaging were unremarkable. Anterior segment examination of the right eye was notable for mild conjunctival injection, fine granulomatous keratic precipitates, mild Descemet’s folds, severe anterior chamber inflammation, focal posterior synechiae and pigment on the anterior lens capsule. The posterior examination of the right eye showed a wedge-shaped region of retinitis superiorly, with a diaphanous leading edge extending down to the superior arcade. The optic nerve appeared healthy. Two small retinal hemorrhages were noted at the temporal edge of the patch of retinitis (Figure 1). Trace hyper- and hypo- autofluorescent changes were noted on autofluorescence imaging, corresponding to the posterior, advancing edge of the patch of retinitis and overall indicating minimal retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) disruption (Figure 2). Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) of the macula was normal (Figure 3A). SD-OCT through the leading edge of the superior retinal lesion showed a variable thickness retinitis with overlying vitritis and thickening of the underlying choroid (Figure 3B). SD-OCT anterior to the leading edge showed a region of atrophic retina with overlying vitritis (Figure 3C). The patient declined fluorescein angiography.

Figure 2:Autofluorescence imaging of the right eye. Note the largely normal autofluorescence, with trace hyper- and hypo-autofluorescent changes corresponding to the posterior, advancing edge of the retinitis.

Figure 3A: SDOCT of the macula of the right eye demonstrates normal foveal contour with no obvious evidence of inflammatory changes.

Figure 3B: SDOCT of the advancing edge of the retinal lesion in the right eye demonstrates variable thickness retinitis with overlying vitritis and thickening of the underlying choroid.

Figure 3C: SDOCT of the region anterior to the leading edge showed patches of atrophic retina with overlying vitritis

The patient was diagnosed with HIV in 2013 and had reportedly been on Genvoya oral therapy (combination of four different medications: elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide) once daily since 2014. Upon further questioning, he admitted to poor compliance with his HIV therapy over the last year. No recent labs were available to determine viral load or CD4 count; the patient reported an absolute CD4 count of >700 (normal range: 490-1740) on his last labs 9 months prior.

The patient was sent to the lab for additional blood testing, including RPR, FTA-ABS, Quantiferon, chest x-ray, toxoplasmosis, HSV-1 and HSV-2, CMV, VZV, EBV, HIV viral load, and CD4 panel. The patient was initiated on prednisolone forte QID OD and cyclopentolate TID OD, as well as valacyclovir 1g TID, pending laboratory results.

Differential Diagnosis

The results were significant for a reactive RPR (1:128) and a positive FTA-ABS, consistent with a diagnosis of syphilis. His absolute CD4 count was 400 (490-1740 cmm), indicating a relatively immunocompromised state. The patient’s primary care provider was contacted, and the patient was sent to the emergency department for lumbar puncture (final result was positive for VDRL in the cerebrospinal fluid) and a 14-day course of IV penicillin G. The patient returned to the retina clinic in one month with improvement of symptoms and a visual acuity of 20/32 OD (previously 20/63). Examination showed near complete resolution of retinitis in the right eye (Figure 4). The patient will continue to follow with retina and infectious disease as an outpatient, with repeat lumbar puncture and serum RPR studies in three months.

Figure 4: Widefield photograph of the right eye, one month after initial diagnosis and after treatment with IV penicillin G. Note the near complete resolution of retinitis superiorly, with some residual vitritis.

Worldwide, there are an estimated 10 million new cases of syphilis annually, with higher rates in men who have sex with men and those who are coinfected with HIV.1-3 Ocular manifestations can occur early or late in the course of infection and are often associated with neurosyphilis.1-3

Uveitis is the most common ocular manifestation of syphilis, with a prevalence of 0.7% to 16.4% among infected patients and higher rates of occurrence in HIV positive patients.1,4 Anterior segment findings can include papillary conjunctivitis, episceral or scleral inflammation, interstitial keratitis, granulomatous or nongranulomatous keratic precipitates, and iritis. Posterior manifestations include vitritis, vasculitis, papillitis, exudative retinal detachment, uveal effusion, central retinal vein occlusion, retinal necrosis, and acute posterior placoid chorioretinitis.5 Of note, it is important to rule out syphilis in a patient presenting with signs of acute posterior placoid pigment epitheliopathy (APMPPE) and atypical serpiginous choroidopathy, as the use of intravitreal corticosteroids or systemic immunosuppressive therapy in this presumed condition may worsen an underlying infection.1

One of the classic fundus findings in syphilis is acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis (ASPPC), which is characterized by single or multiple, non-elevated (placoid), geographic, yellow-white chorioretinal lesions that are often confluent in the posterior pole and peripapillary region (for further details, see Februrary , 2021 Case of the Month by Dr. Braden Burckhard).6-10 However, there have been an increasing number of reports of syphilis patients, especially in the population of men who have sex with men, who present with fundus findings similar to acute retinal necrosis, as was seen in our patient.6,7 These findings include a characteristic ground glass, translucent appearance of unifocal or multifocal lesions, primarily affecting the inner retina and sometimes associated with co-localizing occlusive vasculitis.6,7,11,12 While these syphilitic lesions have previously been described as wedge-shaped, the leading or brushfire-type edge, which was noted in our patient and frequently occurs in CMV retinitis, is less common in syphilis.11 Another interesting feature of syphilitic retinitis is that it heals with minimal disruption of the underlying RPE.6 Overall, this presentation has now been reported in one-third of cases of ocular syphilis; the placoid lesion makes up another third while nonspecific anterior uveitis, disc edema, and vasculitis make up the remaining third.6

Often referred to as the “great imitator,” ocular syphilis requires a high level of clinical suspicion. Serologic testing with nontreponemal and treponemal tests is most commonly used in ophthalmic clinical practice. Non treponemal tests detect the antibody to cardiolipin cholesterol antigen, and examples are Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests. The primary purpose of these tests is screening in a population with low prevalence of syphilis, and monitoring treatment efficacy with titer levels.1,2 Treponemal tests, on the other hand, are more specific than nontreponemal tests. Examples are fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) and the microhemagglutination assay for T. pallidum (MHA-TP). However, these tests are more costly and may have a high rate of false positives in a low-risk population. Generally, once these tests are positive, they remain so for life.1,2

Once ocular syphilis has been diagnosed, cerebrospinal fluid testing is warranted to evaluate for neurosyphilis.1313 Treatment for ocular syphilis, with or without neurosyphilis, is 3-4 million units of aqueous IV penicillin G every four hours for 14 days is the recommended treatment.1,2,13 For patients with a penicillin allergy, desensitization is recommended over alternative antibiotics, especially in those who are co-infected with HIV.1,13 Co-management with an infectious disease specialist is recommended. Sexual partners must be identified, evaluated, and treated. The case must be reported to the state or local public health agency.1-3 Response to therapy may be assessed by improvement in clinical findings and decrease in nontreponemal titers, by four-fold at three months and eight-fold at six months (though this metric does not apply to HIV-positive patients who require more aggressive control).1-3 Adjunctive therapy with topical and oral corticosteroids to control intraocular inflammation may be initiated once the infection has been appropriately treated.1,2 Outcomes are favorable in cases of early diagnosis and adequate therapy, often resulting in full and rapid visual recovery.1,14